A Contrarian Perspective About Economic Forecasts

Of what value to a business owner is a forecast for GDP of +

A Contrarian Perspective About Economic Forecasts

Of what value to a business owner is a forecast for GDP of +2% for 2012? Not much. What most business owners are trying to understand is this: “Are other businesses experiencing what I am?” They are also wondering: “Is there an underlying trend that will make my business decisions less or more risky?”

I was recently reminded of an old saying: You know economists have a sense of humor when they use decimals in their forecasts. There is a misplaced trust in the forecasting process as some kind of physical science when forecasting is really barely an art. The reasons executives want forecasts is that they are seeking some kind of number to calibrate their expectations so they can allocate their resources accordingly. But, this has never been enough for managers to have. It's been enough to justify a forecast or a budget for approval, but it's not really enough.

What managers really need is a collection of multiple future scenarios that they evaluate often. Forecasting is best used as a strategic tool that is constantly raises questions. Even though it involves statistical data, forecasting is a qualitative process, not a quantitative one. The fact that numbers are involved in forecasting gives an illusion of precision that can mislead managerial decision-making.

Economic forecasts are built on foundation that looks backwards. All economic forecasts have a degree of historical extrapolation based on previous market conditions that may no longer exist in the future. Recently, I was at a few venues where I explained that all forecasting models do is take a series of numbers and try to find a pattern to them. Models have no understanding of regulation, customer characteristics, executive knowledge, technological shifts, or world events. They're just numbers. We use the models as a tool to help us understand how all of these factors worked in the past, because it is hard for us to discern patterns, or we are emotionally tied to certain expectations or the history that the data reflect.

Also, there is the assumption that the overall economy reflects what is happening in an industry or in a company. We know that the economy is very dynamic, and that there are always situational issues in every company's fortunes, good and bad.

The purpose of management is to create situations that are different than the market's underlying trends, such as finding ways to increase profits by changing costs when the economy might be difficult. If an industry is contracting, that is an aggregate trend of the total of all businesses in that industry. It is not a destiny for individual businesses. If it is a certain and predictable destiny, then we do not need leaders or managers. The job of management is to view a marketplace, organize resources, and create a superior outcome for that individual company.

Overly relying on economic data is like driving while only looking at the rear view mirror. It has its place as a management tool, but it's not the way to run a business. Just like your car, if you are not paying attention to what’s coming at you from the front, the outcome is likely to be a nasty crash.

The Updated US Commercial Printing Forecast, 2012-2018

The updated forecast table is in our

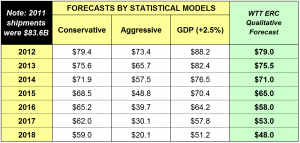

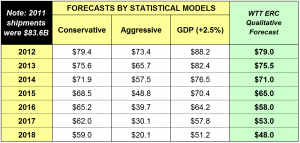

online commercial printing data spreadsheet. With all of the comments about the use of forecasted data stated above, it is important to note some methodological details about the creation of this chart. I apologize for the boring nature of the details, but they are important. First, all data are in January 2012 dollars. The first two columns, “conservative” and “aggressive” are forecasts we run through our forecasting software every month as new monthly printing shipments data are released by the Department of Commerce. We take those current dollar data, inflation-adjust them using the Consumer Price Index for the entire history for each month (the data series goes back to 1992) and then forecast 12-month moving totals of the value of industry shipments. We use 12-month totals so we are always forecasting the value for a full year; this smooths the data and reduces overall statistical forecasting error. For a discussion of the issues involved in inflation-adjusted data, we strongly recommend

our slide show about the topic (and that perhaps you bring a pillow; it's had over 750 views, and we suspect that some might be from an insomnia study at some medical school). Below is the latest forecast table; click to enlarge.

Always remember that the first three columns are just data from statistical models. By definition assumption is that the marketplace conditions that created the statistical patterns are still intact. One model regularly produces forecasts with small changes, so we call it the “conservative” model. The other model puts heavier weights on recent changes, and can produce large directional changes, so we call that the “aggressive” model. We like this model not because it is unfortunately accurate to the downside much too often for our liking (creating the persona of “Dr. Doom”), but because it does produce forecasts that stimulate strategic discussion.

The next column is the result of a linear regression model that uses Real GDP (which is inflation adjusted by the Bureau of Economic Analysis using the Personal Consumption Expenditures inflation factor) to forecast CPI-adjusted print volume. (We have tried other combinations of inflation adjustment, such as PCE- and PPI-adjusted printing shipments, and also using unadjusted GDP and unadjusted printing shipments, but the CPI-adjusted is the only one that produces an r-squared of close to 70%). We assume a long-term GDP real growth rate of +2.5% per year. For comparison, the post-WWII rate has been +3.4%, and the last decade was +1.7%. In light of the bad statistical validity of the GDP models we were using in the past, we now start the GDP data series from 2000. This improved its statistical validity, and produced more sensible forecasts, though the first couple of years in the chart look much too high.

As far as the relationship with GDP goes, it is negative. That is, increases in the growth of GDP results in a lower volume of printing shipments, according to the model. It does seem counterintuitive, since a rising economy is supposed to raise all boats. What seems to happen is that it creates a pool of investment that goes to further and broader investment in digital communications, making them more affordable, and bringing more people into the market. We've discussed this many times; it is not since the 1980s, for the most part, that print volume has exceeded GDP on any consistent basis, and it has lagged GDP for almost two decades. In 1987, commercial printing shipments were 1.34% of GDP; in 2011 they were 0.55%.

Finally, the last column is our judgmental forecast, created by our examination of the statistical forecasts and our qualitative overview of the media, consumer, demographic, and technology trends, that affect our industry. This is the forecast we're hanging our hat on. We update it again, mid-year.

Use the forecast table well... and remember that the purpose of management is to look at the forecasts and expectations, and determine the best way to use the “lay of the land” that they reflect, and defy those trends with good strategy, well-implemented tactics, with a proactive approach to client needs.

In Monday's Column

The column of Monday, February 20 will be one of the more important ones that I have presented. For your reading assignment, look at these three items that will be explored in greater detail in that column. I believe they are indications of what's ahead, and why it is becoming increasingly urgent for print business owners to take decisive actions to get ahead of the trends and their client needs:

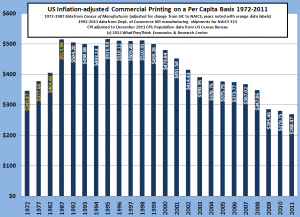

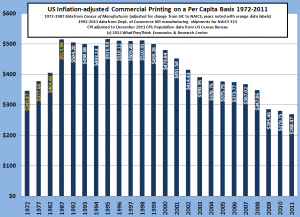

And also ponder this chart of commercial printing on a per capita basis (click to enlarge; may have to click again on the page that opens)... see you on Monday...

Always remember that the first three columns are just data from statistical models. By definition assumption is that the marketplace conditions that created the statistical patterns are still intact. One model regularly produces forecasts with small changes, so we call it the “conservative” model. The other model puts heavier weights on recent changes, and can produce large directional changes, so we call that the “aggressive” model. We like this model not because it is unfortunately accurate to the downside much too often for our liking (creating the persona of “Dr. Doom”), but because it does produce forecasts that stimulate strategic discussion.

The next column is the result of a linear regression model that uses Real GDP (which is inflation adjusted by the Bureau of Economic Analysis using the Personal Consumption Expenditures inflation factor) to forecast CPI-adjusted print volume. (We have tried other combinations of inflation adjustment, such as PCE- and PPI-adjusted printing shipments, and also using unadjusted GDP and unadjusted printing shipments, but the CPI-adjusted is the only one that produces an r-squared of close to 70%). We assume a long-term GDP real growth rate of +2.5% per year. For comparison, the post-WWII rate has been +3.4%, and the last decade was +1.7%. In light of the bad statistical validity of the GDP models we were using in the past, we now start the GDP data series from 2000. This improved its statistical validity, and produced more sensible forecasts, though the first couple of years in the chart look much too high.

As far as the relationship with GDP goes, it is negative. That is, increases in the growth of GDP results in a lower volume of printing shipments, according to the model. It does seem counterintuitive, since a rising economy is supposed to raise all boats. What seems to happen is that it creates a pool of investment that goes to further and broader investment in digital communications, making them more affordable, and bringing more people into the market. We've discussed this many times; it is not since the 1980s, for the most part, that print volume has exceeded GDP on any consistent basis, and it has lagged GDP for almost two decades. In 1987, commercial printing shipments were 1.34% of GDP; in 2011 they were 0.55%.

Finally, the last column is our judgmental forecast, created by our examination of the statistical forecasts and our qualitative overview of the media, consumer, demographic, and technology trends, that affect our industry. This is the forecast we're hanging our hat on. We update it again, mid-year.

Use the forecast table well... and remember that the purpose of management is to look at the forecasts and expectations, and determine the best way to use the “lay of the land” that they reflect, and defy those trends with good strategy, well-implemented tactics, with a proactive approach to client needs.

In Monday's Column

The column of Monday, February 20 will be one of the more important ones that I have presented. For your reading assignment, look at these three items that will be explored in greater detail in that column. I believe they are indications of what's ahead, and why it is becoming increasingly urgent for print business owners to take decisive actions to get ahead of the trends and their client needs:

Always remember that the first three columns are just data from statistical models. By definition assumption is that the marketplace conditions that created the statistical patterns are still intact. One model regularly produces forecasts with small changes, so we call it the “conservative” model. The other model puts heavier weights on recent changes, and can produce large directional changes, so we call that the “aggressive” model. We like this model not because it is unfortunately accurate to the downside much too often for our liking (creating the persona of “Dr. Doom”), but because it does produce forecasts that stimulate strategic discussion.

The next column is the result of a linear regression model that uses Real GDP (which is inflation adjusted by the Bureau of Economic Analysis using the Personal Consumption Expenditures inflation factor) to forecast CPI-adjusted print volume. (We have tried other combinations of inflation adjustment, such as PCE- and PPI-adjusted printing shipments, and also using unadjusted GDP and unadjusted printing shipments, but the CPI-adjusted is the only one that produces an r-squared of close to 70%). We assume a long-term GDP real growth rate of +2.5% per year. For comparison, the post-WWII rate has been +3.4%, and the last decade was +1.7%. In light of the bad statistical validity of the GDP models we were using in the past, we now start the GDP data series from 2000. This improved its statistical validity, and produced more sensible forecasts, though the first couple of years in the chart look much too high.

As far as the relationship with GDP goes, it is negative. That is, increases in the growth of GDP results in a lower volume of printing shipments, according to the model. It does seem counterintuitive, since a rising economy is supposed to raise all boats. What seems to happen is that it creates a pool of investment that goes to further and broader investment in digital communications, making them more affordable, and bringing more people into the market. We've discussed this many times; it is not since the 1980s, for the most part, that print volume has exceeded GDP on any consistent basis, and it has lagged GDP for almost two decades. In 1987, commercial printing shipments were 1.34% of GDP; in 2011 they were 0.55%.

Finally, the last column is our judgmental forecast, created by our examination of the statistical forecasts and our qualitative overview of the media, consumer, demographic, and technology trends, that affect our industry. This is the forecast we're hanging our hat on. We update it again, mid-year.

Use the forecast table well... and remember that the purpose of management is to look at the forecasts and expectations, and determine the best way to use the “lay of the land” that they reflect, and defy those trends with good strategy, well-implemented tactics, with a proactive approach to client needs.

In Monday's Column

The column of Monday, February 20 will be one of the more important ones that I have presented. For your reading assignment, look at these three items that will be explored in greater detail in that column. I believe they are indications of what's ahead, and why it is becoming increasingly urgent for print business owners to take decisive actions to get ahead of the trends and their client needs: