Last week's unemployment report was generally viewed as positive, even though the unemployment rate rose from 5.6% to 5.7%. Extended to an additional decimal point, the actual difference was a change from 5.56% to 5.71%. There was good reason to view it as one of the better reports of late. But overall, it was more similar to the prior report than it was a leap forward.

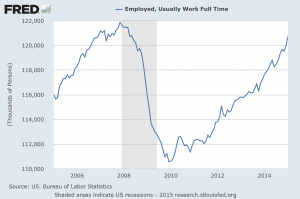

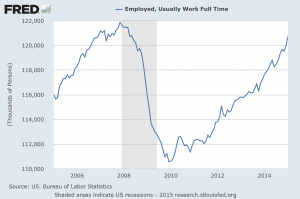

The February employment report is the time when the Bureau of Labor Statistics adjusts their population estimates and revises recent historical data in light of the actual filings of employment reports by businesses and organizations. This report did not change many measures of employment like the labor participation rate and the employment-population ratio to any great degree. In many ways, this report was flat with last month. It's better to look at this in terms of how things have changed over the last year. The labor force has increased by about 1.7 million people. There are nearly 3 million more people employed today. The employment-population ratio, still at decades-low levels, improved from 58.8% to 59.3%. The number of unemployed workers fell by 1.3 million (this does not include long-term discouraged workers). The unemployment rate improved from 6.6% to 5.7%. The trend of people leaving the workforce continued, however, as 1.1 were added to the "not in labor force" figure, which is now up to 92.5 million. Full time jobs have still not reached pre-recession levels, and adjusted for population growth, are short in the range of about 7-9 million workers, depending on the population growth rate you use. (click to enlarge)

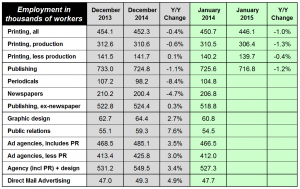

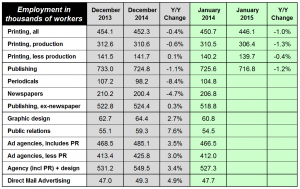

The original reports had 2014 printing employment down -1.37%, and that has been revised to -0.4%. Employment increased slightly mid-2014 when shipments were improving, and then slightly declined in November and December. Employment peaked in June 2014 at 455,700, and by December fell to 452,300. That was still 13,400 more than originally reported. Employment fell again in January 2015 to 446,100, which is 4,600 lower than January 2014. (click chart to enlarge)

January 2015 employment in printing is -1% lower than 2014. Periodicals employment (mainly magazines) for December 2014 was 98,200 and decreased by 9,000 (-8.4%) compared to 2013. Newspaper employment was down -9,800 (-4.7%). The biggest percentage growth was public relations, finishing 2014 at 59,300 (excludes freelancers), an increase of +7.6%. Excluding public relations, advertising agency employment was up by 12,400 (+3%).

* * *

Jim Clifton, the Chairman of Gallup caused quite a stir with his opinion piece "

The Big Lie: 5.6% Unemployment." The piece referred to last months employment report.

Right now, we're hearing much celebrating from the media, the White House and Wall Street about how unemployment is "down" to 5.6%. The cheerleading for this number is deafening. The media loves a comeback story, the White House wants to score political points and Wall Street would like you to stay in the market.

None of them will tell you this: If you, a family member or anyone is unemployed and has subsequently given up on finding a job -- if you are so hopelessly out of work that you've stopped looking over the past four weeks -- the Department of Labor doesn't count you as unemployed. That's right. While you are as unemployed as one can possibly be, and tragically may never find work again, you are not counted in the figure we see relentlessly in the news -- currently 5.6%. Right now, as many as 30 million Americans are either out of work or severely underemployed. Trust me, the vast majority of them aren't throwing parties to toast "falling" unemployment.

There's another reason why the official rate is misleading. Say you're an out-of-work engineer or healthcare worker or construction worker or retail manager: If you perform a minimum of one hour of work in a week and are paid at least $20 -- maybe someone pays you to mow their lawn -- you're not officially counted as unemployed in the much-reported 5.6%. Few Americans know this.

Yet another figure of importance that doesn't get much press: those working part time but wanting full-time work. If you have a degree in chemistry or math and are working 10 hours part time because it is all you can find -- in other words, you are severely underemployed -- the government doesn't count you in the 5.6%. Few Americans know this.

Why Clifton decided to write this now is unknown. It could have been written all the way through the recovery. Regular readers here know much of what he cites is true and that the Bureau of Labor Statistics reports these data if you take the time to look for them in their press releases.

What might be the case is that Gallup is looking to become an alternative to the BLS reporting. For years they have published their own assessment of employment. What they are probably tired of hearing about is how it does not match the BLS reports closely enough. That's a problem, especially when "everyone" uses the headline numbers from BLS and does not dig into the reports. You usually don't have to dig that deeply, just a few paragraphs more. But even the business press does not seem to do that often.

It's hard to believe that the recession started seven years ago and the employment data in counts of workers still has not reached those levels and that's not a news story. As long as the percentage of unemployed improves, that's all that matters. As managers we know that we have to dig deeper than top numbers show to understand the subtleties of situations. The BLS does not hide key data (they do not release some of their seasonal adjustments, but that's a different story) and it does not take long to find some fascinating trends and conditions. It just helps to be curious.

* * *

An important aspect of employment is the mobility of the workforce. The mortgage crisis froze workers in place until they could solve their housing problems. This is still an issue today. The

Wall Street Journal had an article about how apartment and home rentals are growing.

Renters made up the majority of the population in cities at the core of nine of the nation’s 11 largest metro areas in 2013, a sharp change from 2006, when renters were the majority in just five of those cities, according to a new report...

Texas cities have seen explosive job growth, drawing many transplanted younger workers with entry-level or middle-income jobs. Dallas-based apartment developer Brad Miller said the young people he sees prefer to rent and want to be able to pick up and move to places such as Denver at a moment’s notice without having to worry about whether they can sell a condominium. “They’ll go where the jobs are and where the money is,” said Mr. Miller, president of Encore Multi-Family.

Home ownership is an important goal for the benefits of stability to neighborhoods and as a potential store of value for financial security. But it should not be forced, which is what housing programs have done in the past. Rentals are a way to ensure workforce mobility that reduces costs and risks of such moves. A workforce that is free to move geographically is important to a healthy economy that more easily adjusts to change.

* * *

Academics and policymakers have wondered what the effect of unemployment payments are on the unemployment rate and on the speed of economic recoveries. It has always been suspected, with good reason from data available, that increasing the duration of benefits slows the recovery of employment. There is also the effect that the longer a person is out of work the more likely their skills will be out of date and the less relevant their experience will be.

The National Bureau of Economic Research, the same academic organization that officially determines the starting and ending dates of recessions and recoveries, has published a paper that analyzed this latest recovery. Of the 3 million increase in jobs, the researchers believe that 1.8 million were due to the expiration of unemployment benefits. That is, a high percentage of people accepted jobs only when their benefits expired. While some may attribute this to some nefarious desire to take money for not working, it is usually the desire to find a job that most closely matched their prior one in terms of job requirements and pay. When the benefits expire, they "settle" for something else and rejoin the employed workforce. Not all states extended benefits expired at the same time, so the researchers were able to see before and after effects under different conditions. For many months we had seen news stories that small businesses had positions that were difficult to fill. Workers with expired benefits re-entered the labor force and may took those jobs. In the 2013, job creation rate was lower than the national average in the states with the most generous benefits. After those benefits expired in 2014, those states job creation rates were higher than the national average.

A PDF of the report can be

downloaded for free.

It was reported in the

Washington Post, National Review, The Economist, and the

Wall Street Journal.

The

site of one of the researchers has links to articles and analyses that disagree with their work, and includes the responses the authors made.

# # #

The original reports had 2014 printing employment down -1.37%, and that has been revised to -0.4%. Employment increased slightly mid-2014 when shipments were improving, and then slightly declined in November and December. Employment peaked in June 2014 at 455,700, and by December fell to 452,300. That was still 13,400 more than originally reported. Employment fell again in January 2015 to 446,100, which is 4,600 lower than January 2014. (click chart to enlarge)

The original reports had 2014 printing employment down -1.37%, and that has been revised to -0.4%. Employment increased slightly mid-2014 when shipments were improving, and then slightly declined in November and December. Employment peaked in June 2014 at 455,700, and by December fell to 452,300. That was still 13,400 more than originally reported. Employment fell again in January 2015 to 446,100, which is 4,600 lower than January 2014. (click chart to enlarge)

January 2015 employment in printing is -1% lower than 2014. Periodicals employment (mainly magazines) for December 2014 was 98,200 and decreased by 9,000 (-8.4%) compared to 2013. Newspaper employment was down -9,800 (-4.7%). The biggest percentage growth was public relations, finishing 2014 at 59,300 (excludes freelancers), an increase of +7.6%. Excluding public relations, advertising agency employment was up by 12,400 (+3%).

* * *

Jim Clifton, the Chairman of Gallup caused quite a stir with his opinion piece "The Big Lie: 5.6% Unemployment." The piece referred to last months employment report.

January 2015 employment in printing is -1% lower than 2014. Periodicals employment (mainly magazines) for December 2014 was 98,200 and decreased by 9,000 (-8.4%) compared to 2013. Newspaper employment was down -9,800 (-4.7%). The biggest percentage growth was public relations, finishing 2014 at 59,300 (excludes freelancers), an increase of +7.6%. Excluding public relations, advertising agency employment was up by 12,400 (+3%).

* * *

Jim Clifton, the Chairman of Gallup caused quite a stir with his opinion piece "The Big Lie: 5.6% Unemployment." The piece referred to last months employment report.