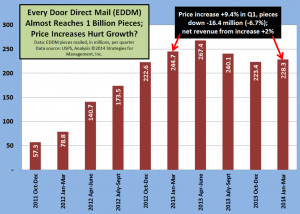

Welcome to the always interesting world of USPS pricing strategy. Where else can someone say that they raised prices +9.4% and wonder why volume went down -6.7% and revenues only went up +2% compared to the same period of the prior year. Perhaps it was the weather, which got the blame for all things economic in Q1! (click chart to enlarge)

Maybe it's time to conduct a study. They already did. The USPS funded economic research released in May 2013 that shows increases in postal rates have no effect on volume. The economic phrase is that demand is “inelastic,” or mostly insensitive to price changes whether prices go up or down. Read the statistics-laden report (if you can). You should not have to pull out that must statistical artillery to torture data to come out with results that defy common sense. The report was complete in terms of identifying the factors that affect postal demand, such as consumer tastes, population, and alternative media.

But let the report speak for itself:

The demand for the postal products studied is price inelastic. Price increases will increase revenues. Decreases in postal prices, either through price cuts or widespread use of discounting, will reduce Postal Service revenues.

There are many issues one can have with the analysis, but the underlying theme (not expressly stated) but fair to conclude: Virtually all of the postal demand declines are solely the result of digital alternatives and not due to USPS pricing. The report essentially encourages the USPS to act to increase prices, such as the exigent price increase in December 2013 (on Christmas Eve), and to make the case for future ones if they are allowed to.

Postage is not the only cost of mailing; the discounts that the USPS offers on postage require a shifting of work to mailers and their suppliers. That shifting requires investment in capital (time, knowledge, technology, people) that has short- and long-term costs. Those costs are not fully understood, but they become barriers to entry for new mailers, and concentrate mailing capabilities to a smaller group of competitors that can justify those investments. Some of those costs are minor (software tweaks), some are major (new equipment), some are opportunity costs (work for which discount achievement is not practical, so it shifts to another medium, or changes quantities or format, changes in frequency or page count, or is not done). It's not just work-shifting, it's capital- and risk-shifting. Those are not always visible to the marketplace but are the kinds of judgments that are made every day in the natural course of business.

Therefore the assessment of “price” from the USPS perspective does not include the prices for goods and actions that USPS customers and their suppliers must make to work with the USPS distribution system. That is, the USPS views its “price” as separate and distinct, and not as part of a total cost of print communications that use their services. It does not include the costs or changes that USPS customers make to adjust their total costs, or to forgo potential revenues, in response to USPS prices. Nor are the costs of implementing alternatives, and nor are value of any of the benefits of any of the media considered as having an effect on demand.

Marketers and communicators make their decisions on a total cost basis, not on a USPS-cost-alone basis. This means that rises in postal costs are likely to lead to harder negotiations with other suppliers in the chain. Because postal services are essential to postal media because of their legal monopoly, the prices of other necessary components may be affected. While printing prices are also affected by other media, postage price increases may be a primary reason why printing prices do not rise with inflation. USPS increases "crowd out" attempts by printers to increase prices to reflect their own increased costs of paper and other materials and services that are needed to produce goods that are mailed. So profits and wages become constrained among those who create and supply the materials that go through the USPS system. Capital investments are partly directed to complying with USPS regulations rather than innovation in detecting and satisfying customer objectives. USPS price strategies end up trying to grab a bigger slice of a total dollars pie, a pie that its decisions is causing to shrink.

In the case of EDDM, it is a relatively new product, and was not included in the USPS price elasticity analysis. Whether or not this one year-to-year quarterly comparison will be seen in future data remains to be seen. It is a possible indication that price elasticity does exist, at least for this product.

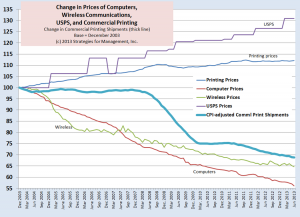

One of the problems is the constant comparison of USPS prices to the Consumer Price Index and not the prices of competitors. The chart below shows the growing wide disparity between USPS prices, printing prices, computer prices, and wireless communications. It's almost like how the Universe can expand faster than the speed of light: it moves in two opposite directions at the same time. So it's not the comparison between inflation and postal prices, it's the combination of the difference between its price trajectory and the price trajectory of others. (click chart to enlarge)

So, if inflation is 2% and wireless communications prices decrease by -3%, that is a five percentage point gap. The USPS does not view it that way, unfortunately. (Some inside the USPS may view it that way, but they may not be allowed to act on that view because of regulatory constraints). That gap is one of the factors driving the shift to other media, of course.

The report only justifies the dynamic inertia that the USPS seems to have ingrained in its structure. The Postal Regulatory Commission will meet on August 14 to study the price elasticity subject (again).

If the USPS was a “real business,” and not this constrained hybrid, they'd have figured this out a long time ago at a sales meeting rather than waiting for a commission. Stockholders would have clamored for a change in strategy (and perhaps management), demanding that the direction of revenues be reversed. But by law USPS can't be a “real” business, since they can't respond to, or pre-empt, competitor actions in a timely and interesting way. Instead, they proceed on the same course, by law, fighting little battles here and there that often make things “less worse” than a “little better.” In the end, they ignore true competitors and end up giving those competitors an easy and unresponsive target.

No one knows what the market price for postage is because buyers and sellers can't negotiate them. The USPS can't run “sales” designed that flatten out their seasonal peaks and valleys of volume. They can't run something similar to “early bird specials” that flatten out waiting times of customers or encourage mailing items on “slow days.” They can't charge more for “peak times.” Nor can they aggressively develop new business and take business risks of new products. (Good interview at the WSJ with some entrepreneurs who tried to help, being told “You disrupt my service and we will never work with you.”)

There is a chance that postage might actually settle at market prices that are higher than they are today. Postal rates may be subject to wide seasonal variations. Postal rates might have regional differences. Mailers might be willing to buy futures contracts on mail services. We'll never know. Anyone who claims to know doesn't. Everyone's living the fable about the blind men and the elephant. No one's willing to take the risks of actually finding out by letting market interactions set prices. Instead, everyone lines up along the same predictable positions, the USPS explaining it has cost increases and the users pleading imminent catastrophe.

EDDM has been one of the few initiatives that filled the needs of small local businesses, especially local retailers, like realtors and restaurants. These businesses have little time for data base management or maintaining customers lists. But they do know the geography of their stores and customers. Sure, EDDM should have been a USPS offering a long time ago, but we'll take it now. It's a great product, and more printers should be promoting it. Let's see how the next quarter's data look. Let's hope we don't end up saying “Poor EDDM... ya coulda been a contenda.”

* * *

One of the problems with statistical models used in the USPS elasticity report is the problem with all models: you have to rely on historical data. The future is, by definition, unknown, if not unknowable, yet it's critical to have an understanding of it because resources have to be gathered and deployed for future times. This is why businesspeople and entrepreneurs are so interested in the outlooks of others and need develop assumptions about the future on their own.When markets change, statistics rarely reflect them immediately. Most all changes start small. The first variations most always appear to be within the normal ranges of statistical variability or acceptable statistical error. This is what happened when commercial print fell off its GDP relationship in the late 1990s. For years, the forecasting “misses” fell within the range of expected statistical errors. Then those “misses” started to appear and pile up only in one direction and not have the random variability of positive and negative variations.

Unfortunately, it can take years for new patterns to become evident and for them to have a degree of statistical reliability. When statistical models start to deteriorate, it's a sign of change in the marketplace. How many quarters can that take? Four? The statisticians will want more observations. Eight? The statisticians may comment about patterns starting to appear.

Businesspeople can't wait for that to happen. By the time the new statistical relationships are sturdy, it's too late. They have to make judgments now, and place their careers, incomes, personal savings, and personal responsibilities on the line on a regular basis.

There's another aspect of quantitative models that is very important. All models reflect the data that they use. No, this is not a “garbage in, garbage out” thing. This is that data reflect the history of the results of business decisions and their context of past periods, not periods that have yet to occur. That is, they are the products of the business environments that existed at that time.

Models at best create a baseline that should be the start of planning discussions, not the answer to them. Strategic questions about the nature of the business environment, the actions of competitors, the needs and objectives of customers, changes to customer marketplaces, and numerous other topics need to be explored. One hopes that the USPS elasticity analysis was met with those kinds of discussions.

Back in the development of the Polaris submarine, Admiral Rickover is rumored to have said that the development of their planning models (PERT, the Program and Evaluation Review Technique) was intended to keep the bureaucrats from interfering in operations. I've used PERT and I've even taught it (those poor students!). It's a great management tool. But I can't find a reference to the wry Rickover statement even though I have heard about it many times. What we do have is a similar statement made by him about the production of weapons systems quoted in a book “Defense Acquisition Reform, 1960–2009: An Elusive Goal” by J. Ronald Fox:

So long as the bureaucracy consists of large numbers of people at many levels who believe they perform their function of evaluation and approval properly, by requiring vast and detailed information to be submitted through the many levels of the bureaucracy, program managers will never be found who can effectively manage their jobs. A program manager today would require at least 48 hours a day of his own time just to satisfy the requests for detailed information from the Navy and DoD bureaucracies, the Congress, the General Accounting Office [GAO], and various other parties who have the legal right—and use it—to place demands on his time. As long as we operate a system where the checkers (those charged with the responsibility of evaluating and approving) outnumber the doers (those responsible for carrying out the work), the doers are condemned to spend their time doing paper work for the checkers.

This has been one of the downsides of organizations as they expand. Responsibility becomes diffuse and there are specialized jobs that create reports to defend the importance of their positions and the decisions they make. Making reports becomes just as important as making things.

* * *

When I was studying quantitative analysis so many years ago, some of the faculty members had outside consulting projects where they knew the creation of the models they were working on were to justify decisions that already been made, some already being implemented. They also complained that people were using models to “predict the past.” They had enough jobs where they were solving real problems, but these others were always discouraging to them.

Vanguard, the financial giant, had a marvelous report recently about “back-testing” of financial models and how data could be mis-used to justify certain investment strategies. The satirical blogpost (with a convincing chart) about the “alphabet strategy” explained how they found 26 investing strategies that handily beat the S&P 500 index since 1994. Barron's explained it as follows:

He did it by grouping all S&P 500 stocks by letter of the alphabet, equal-weighting the groups. Alcoa (AA) and Apple (AAPL) go with the A’s, Berkshire Hathaway (BRKA, BRKB) and Broadcom (BRCM) go with the B’s, etc. The equal weighting shaves the large stocks’ disproportionate influence.

A relative of mine, new to the workforce, saw his first top management budget process a couple of years ago. He was discouraged that figures were pulled from “thin air” because they “made the numbers work” rather than reflecting what was really going on. I told him that one day he might be doing the same exact thing.

Are your planning sessions justifying and perpetuating the past or creating a proactive, forward-thinking organization. Stop managing by the rear-view mirror. Businesses that manage by the past either won't see where they're going or they're admitting they are afraid to look.

* * *

I've long suggested that the USPS be freed from its regulatory shackles, turned into a public company owned 50% by its employees and its pension funds (which would no longer be an obligation of the Treasury for many of its workers). The UK privatized much of the Royal Mail operation last year; it was messy, but it was done. My suggestion is impossible to implement. It's easy to fly a desk into battle, isn't it?

* * *

Royal Mail's founder, Henry VIII, was famous for reasons other than mail. You may have heard about six of them.

* * *

I've always enjoyed the story of libertarian Lysander Spooner who formed the Great American Mail Company to compete with the Post Office. It was shut down by an act of Congress.

# # #

NOTE: A reader made the comment that I erred in referring to the "Postal Rate Commission." It's the "Postal Regulatory Commission." The error has been corrected above. The website is prc.gov.