Even slowing inflation needs to be put in context. Over a 10-year period, supposedly moderate inflation of 2% per year means that a dollar loses more than 20% of its purchasing power, even more when compounding is considered.

The slowdown in prices probably reflects a slowdown in the global economy, and what may be considered another recession.

Of greatest concern is that real earnings, that is, the average worker earnings after adjustment for inflation is still going down. The economy is growing, though at very slow rates, but earnings continue to erode. This is a serious problem, as productivity is still rising, and workers are not benefiting from it. Businesses, unable to pass on all of their increased costs (PPI has been greater than CPI for quite a long time), pay for those costs by reducing expenditures in other areas. As mentioned in last week's note, the economy is still in efficiency mode, and lacks and expansionary movement. Risks are not considered worth their costs, while making internal operations better, or at least cost less, has an immediate and measurable impact.

Many businesspeople are a bit confused about the CPI. I have had the experience many times where someone, whom I know reads the paper every day and pays attention to business news, would claim that the CPI does not include food or energy. It does, but so many of these economic measures are just a blur to everyone. What he was talking about was “core CPI,” which does exclude food and energy, because those are considered to be so volatile from month to month that they can give false signals as to the direction of inflation in short periods of time. The business media loves reporting core CPI for some reason, which may, after so many years of doing it, be just out of habit. The academic literature has shown than core CPI is not that good an indicator, and that the regular CPI reporting conveys inflation just fine.

Core CPI should create a logical concern, but no one seems to ask the question. What if wages are low, as they are now, and those lower wages are keeping food and energy prices from rising? Is the decreasing amounts of wages distorting the core CPI. I would contend that it does, and I believe it is misleading policymakers into making false assumptions about inflation, such as inflation being “tame.” It's not. If prices were flat, but your income fell, goods would cost more to you. So inflation could be zero, but the prices would be out of reach. That's just as bad as inflation.

* * *

Next week, we get the first estimate of GDP for the third quarter. There is little reason to expect that it will be anything other than in the 2% range in real terms.

Even slowing inflation needs to be put in context. Over a 10-year period, supposedly moderate inflation of 2% per year means that a dollar loses more than 20% of its purchasing power, even more when compounding is considered.

The slowdown in prices probably reflects a slowdown in the global economy, and what may be considered another recession.

Of greatest concern is that real earnings, that is, the average worker earnings after adjustment for inflation is still going down. The economy is growing, though at very slow rates, but earnings continue to erode. This is a serious problem, as productivity is still rising, and workers are not benefiting from it. Businesses, unable to pass on all of their increased costs (PPI has been greater than CPI for quite a long time), pay for those costs by reducing expenditures in other areas. As mentioned in last week's note, the economy is still in efficiency mode, and lacks and expansionary movement. Risks are not considered worth their costs, while making internal operations better, or at least cost less, has an immediate and measurable impact.

Many businesspeople are a bit confused about the CPI. I have had the experience many times where someone, whom I know reads the paper every day and pays attention to business news, would claim that the CPI does not include food or energy. It does, but so many of these economic measures are just a blur to everyone. What he was talking about was “core CPI,” which does exclude food and energy, because those are considered to be so volatile from month to month that they can give false signals as to the direction of inflation in short periods of time. The business media loves reporting core CPI for some reason, which may, after so many years of doing it, be just out of habit. The academic literature has shown than core CPI is not that good an indicator, and that the regular CPI reporting conveys inflation just fine.

Core CPI should create a logical concern, but no one seems to ask the question. What if wages are low, as they are now, and those lower wages are keeping food and energy prices from rising? Is the decreasing amounts of wages distorting the core CPI. I would contend that it does, and I believe it is misleading policymakers into making false assumptions about inflation, such as inflation being “tame.” It's not. If prices were flat, but your income fell, goods would cost more to you. So inflation could be zero, but the prices would be out of reach. That's just as bad as inflation.

* * *

Next week, we get the first estimate of GDP for the third quarter. There is little reason to expect that it will be anything other than in the 2% range in real terms.

Commentary & Analysis

Real Earnings Lessen as Inflation Moderates, Or Is It Rotten to the Core?

Consumer Price Index and Producer Price Index data were released this week,

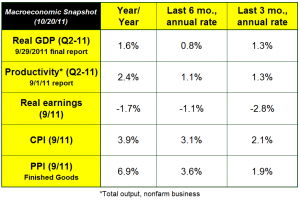

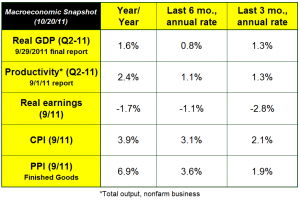

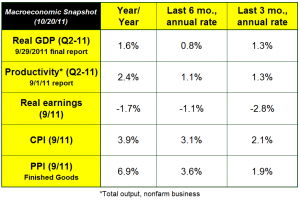

Consumer Price Index and Producer Price Index data were released this week, and both showed some moderation in broader context. The reports of month-to-month change were not good. The CPI rose +0.3%, or +3.6% when annualized, outside of the Fed's target to keep it under +2%. The PPI, the change in the costs of goods when manufactured, went up +0.8%, producing a whopping +9.6% on an annualized basis.

It is better, however, to look at it in wider time frames. Our monthly macroeconomic shapshot shows the annualized rates for the last 12 months, the last 6 months, and the last three months. Over the last three months, inflation appears to be slowing (click table to enlarge).

Even slowing inflation needs to be put in context. Over a 10-year period, supposedly moderate inflation of 2% per year means that a dollar loses more than 20% of its purchasing power, even more when compounding is considered.

The slowdown in prices probably reflects a slowdown in the global economy, and what may be considered another recession.

Of greatest concern is that real earnings, that is, the average worker earnings after adjustment for inflation is still going down. The economy is growing, though at very slow rates, but earnings continue to erode. This is a serious problem, as productivity is still rising, and workers are not benefiting from it. Businesses, unable to pass on all of their increased costs (PPI has been greater than CPI for quite a long time), pay for those costs by reducing expenditures in other areas. As mentioned in last week's note, the economy is still in efficiency mode, and lacks and expansionary movement. Risks are not considered worth their costs, while making internal operations better, or at least cost less, has an immediate and measurable impact.

Many businesspeople are a bit confused about the CPI. I have had the experience many times where someone, whom I know reads the paper every day and pays attention to business news, would claim that the CPI does not include food or energy. It does, but so many of these economic measures are just a blur to everyone. What he was talking about was “core CPI,” which does exclude food and energy, because those are considered to be so volatile from month to month that they can give false signals as to the direction of inflation in short periods of time. The business media loves reporting core CPI for some reason, which may, after so many years of doing it, be just out of habit. The academic literature has shown than core CPI is not that good an indicator, and that the regular CPI reporting conveys inflation just fine.

Core CPI should create a logical concern, but no one seems to ask the question. What if wages are low, as they are now, and those lower wages are keeping food and energy prices from rising? Is the decreasing amounts of wages distorting the core CPI. I would contend that it does, and I believe it is misleading policymakers into making false assumptions about inflation, such as inflation being “tame.” It's not. If prices were flat, but your income fell, goods would cost more to you. So inflation could be zero, but the prices would be out of reach. That's just as bad as inflation.

* * *

Next week, we get the first estimate of GDP for the third quarter. There is little reason to expect that it will be anything other than in the 2% range in real terms.

Even slowing inflation needs to be put in context. Over a 10-year period, supposedly moderate inflation of 2% per year means that a dollar loses more than 20% of its purchasing power, even more when compounding is considered.

The slowdown in prices probably reflects a slowdown in the global economy, and what may be considered another recession.

Of greatest concern is that real earnings, that is, the average worker earnings after adjustment for inflation is still going down. The economy is growing, though at very slow rates, but earnings continue to erode. This is a serious problem, as productivity is still rising, and workers are not benefiting from it. Businesses, unable to pass on all of their increased costs (PPI has been greater than CPI for quite a long time), pay for those costs by reducing expenditures in other areas. As mentioned in last week's note, the economy is still in efficiency mode, and lacks and expansionary movement. Risks are not considered worth their costs, while making internal operations better, or at least cost less, has an immediate and measurable impact.

Many businesspeople are a bit confused about the CPI. I have had the experience many times where someone, whom I know reads the paper every day and pays attention to business news, would claim that the CPI does not include food or energy. It does, but so many of these economic measures are just a blur to everyone. What he was talking about was “core CPI,” which does exclude food and energy, because those are considered to be so volatile from month to month that they can give false signals as to the direction of inflation in short periods of time. The business media loves reporting core CPI for some reason, which may, after so many years of doing it, be just out of habit. The academic literature has shown than core CPI is not that good an indicator, and that the regular CPI reporting conveys inflation just fine.

Core CPI should create a logical concern, but no one seems to ask the question. What if wages are low, as they are now, and those lower wages are keeping food and energy prices from rising? Is the decreasing amounts of wages distorting the core CPI. I would contend that it does, and I believe it is misleading policymakers into making false assumptions about inflation, such as inflation being “tame.” It's not. If prices were flat, but your income fell, goods would cost more to you. So inflation could be zero, but the prices would be out of reach. That's just as bad as inflation.

* * *

Next week, we get the first estimate of GDP for the third quarter. There is little reason to expect that it will be anything other than in the 2% range in real terms.

Even slowing inflation needs to be put in context. Over a 10-year period, supposedly moderate inflation of 2% per year means that a dollar loses more than 20% of its purchasing power, even more when compounding is considered.

The slowdown in prices probably reflects a slowdown in the global economy, and what may be considered another recession.

Of greatest concern is that real earnings, that is, the average worker earnings after adjustment for inflation is still going down. The economy is growing, though at very slow rates, but earnings continue to erode. This is a serious problem, as productivity is still rising, and workers are not benefiting from it. Businesses, unable to pass on all of their increased costs (PPI has been greater than CPI for quite a long time), pay for those costs by reducing expenditures in other areas. As mentioned in last week's note, the economy is still in efficiency mode, and lacks and expansionary movement. Risks are not considered worth their costs, while making internal operations better, or at least cost less, has an immediate and measurable impact.

Many businesspeople are a bit confused about the CPI. I have had the experience many times where someone, whom I know reads the paper every day and pays attention to business news, would claim that the CPI does not include food or energy. It does, but so many of these economic measures are just a blur to everyone. What he was talking about was “core CPI,” which does exclude food and energy, because those are considered to be so volatile from month to month that they can give false signals as to the direction of inflation in short periods of time. The business media loves reporting core CPI for some reason, which may, after so many years of doing it, be just out of habit. The academic literature has shown than core CPI is not that good an indicator, and that the regular CPI reporting conveys inflation just fine.

Core CPI should create a logical concern, but no one seems to ask the question. What if wages are low, as they are now, and those lower wages are keeping food and energy prices from rising? Is the decreasing amounts of wages distorting the core CPI. I would contend that it does, and I believe it is misleading policymakers into making false assumptions about inflation, such as inflation being “tame.” It's not. If prices were flat, but your income fell, goods would cost more to you. So inflation could be zero, but the prices would be out of reach. That's just as bad as inflation.

* * *

Next week, we get the first estimate of GDP for the third quarter. There is little reason to expect that it will be anything other than in the 2% range in real terms.

Even slowing inflation needs to be put in context. Over a 10-year period, supposedly moderate inflation of 2% per year means that a dollar loses more than 20% of its purchasing power, even more when compounding is considered.

The slowdown in prices probably reflects a slowdown in the global economy, and what may be considered another recession.

Of greatest concern is that real earnings, that is, the average worker earnings after adjustment for inflation is still going down. The economy is growing, though at very slow rates, but earnings continue to erode. This is a serious problem, as productivity is still rising, and workers are not benefiting from it. Businesses, unable to pass on all of their increased costs (PPI has been greater than CPI for quite a long time), pay for those costs by reducing expenditures in other areas. As mentioned in last week's note, the economy is still in efficiency mode, and lacks and expansionary movement. Risks are not considered worth their costs, while making internal operations better, or at least cost less, has an immediate and measurable impact.

Many businesspeople are a bit confused about the CPI. I have had the experience many times where someone, whom I know reads the paper every day and pays attention to business news, would claim that the CPI does not include food or energy. It does, but so many of these economic measures are just a blur to everyone. What he was talking about was “core CPI,” which does exclude food and energy, because those are considered to be so volatile from month to month that they can give false signals as to the direction of inflation in short periods of time. The business media loves reporting core CPI for some reason, which may, after so many years of doing it, be just out of habit. The academic literature has shown than core CPI is not that good an indicator, and that the regular CPI reporting conveys inflation just fine.

Core CPI should create a logical concern, but no one seems to ask the question. What if wages are low, as they are now, and those lower wages are keeping food and energy prices from rising? Is the decreasing amounts of wages distorting the core CPI. I would contend that it does, and I believe it is misleading policymakers into making false assumptions about inflation, such as inflation being “tame.” It's not. If prices were flat, but your income fell, goods would cost more to you. So inflation could be zero, but the prices would be out of reach. That's just as bad as inflation.

* * *

Next week, we get the first estimate of GDP for the third quarter. There is little reason to expect that it will be anything other than in the 2% range in real terms.

About Dr. Joe Webb

Dr. Joe Webb is one of the graphic arts industry's best-known consultants, forecasters, and commentators. He is the director of WhatTheyThink's Economics and Research Center.

Video Center

- Questions to ask about inkjet for corrugated packaging

- Can Chinese OEMs challenge Western manufacturers?

- The #1 Question When Selling Inkjet

- Integrator perspective on Konica Minolta printheads

- Surfing the Waves of Inkjet

- Kyocera Nixka talks inkjet integration trends

- B2B Customer Tours

- Keeping Inkjet Tickled Pink

© 2024 WhatTheyThink. All Rights Reserved.