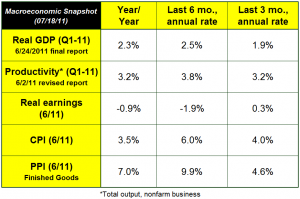

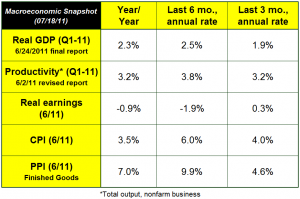

The rates for the CPI and PPI for the last three months are now lower than the six month rates, but even though they are, they are beyond the targeted rates of the Federal Reserve. Real earnings, which is what's in people's paychecks after inflation, is finally showing a small rise, but it might as well be flat. Productivity is still higher than GDP, warning that employment growth will be minimal.

With this overview in mind, it's good to look at where we are since the declared start of the recession in December 2007. Remember, the start of a recession is the last peak of data. So that means that December 2007, or Q4-2007, was the last time things were going well. Since that time, GDP is up +0.6%, so it might as well be flat. Earnings are up +0.9%, which would mean that earnings are rising faster than economic growth, but it doesn't feel that way. Productivity is down -0.1% since that time. The CPI is up +7.4% and the PPI is up +12.4%. Essentially, everything is mainly flat, except for inflation. The cost of staying in the same place has gone up.

The recovery started in June of 2009. Recovery start dates are selected as the low point from the start of the recession. Since that time, GDP is up 5%. Productivity is up +6.6% (again, when productivity is greater than GDP, it implies employment contraction; employment rises when the economy grows faster than productivity). Even though GDP and productivity are up smartly since June 2009, real earnings are down -1.4%. This is why there is such concern for the economy and workers. Other than that there are not enough employed workers, current workers pay is not increasing commensurate with their output. Why? Higher materials prices are eating into business costs, and the easiest place to make up for it is wages, since that is the biggest cost of organizations. The PPI is up +10% since the recovery started, while the CPI is up +4.6%. That disparity gets made up somewhere, and it's in operations. The increased productivity is paying for the increased materials costs.

Where does this lead? There's more muddling ahead. Most all economic forecasters have reduced their forecasts for Q2 and the rest of the year to be in the range of +2% (there were some forecasts of +4% earlier in the year by some of them). Look for forecasts to be revised yet again. On Friday, July 29, GDP for Q2-2011 will be released, but the Bureau of Economic Analysis will be revising their GDP and many other critical data series all the way back to 2003. The data will probably show that the recession was deeper than originally reported. Don't be surprised if the recovery is also downgraded.

The rates for the CPI and PPI for the last three months are now lower than the six month rates, but even though they are, they are beyond the targeted rates of the Federal Reserve. Real earnings, which is what's in people's paychecks after inflation, is finally showing a small rise, but it might as well be flat. Productivity is still higher than GDP, warning that employment growth will be minimal.

With this overview in mind, it's good to look at where we are since the declared start of the recession in December 2007. Remember, the start of a recession is the last peak of data. So that means that December 2007, or Q4-2007, was the last time things were going well. Since that time, GDP is up +0.6%, so it might as well be flat. Earnings are up +0.9%, which would mean that earnings are rising faster than economic growth, but it doesn't feel that way. Productivity is down -0.1% since that time. The CPI is up +7.4% and the PPI is up +12.4%. Essentially, everything is mainly flat, except for inflation. The cost of staying in the same place has gone up.

The recovery started in June of 2009. Recovery start dates are selected as the low point from the start of the recession. Since that time, GDP is up 5%. Productivity is up +6.6% (again, when productivity is greater than GDP, it implies employment contraction; employment rises when the economy grows faster than productivity). Even though GDP and productivity are up smartly since June 2009, real earnings are down -1.4%. This is why there is such concern for the economy and workers. Other than that there are not enough employed workers, current workers pay is not increasing commensurate with their output. Why? Higher materials prices are eating into business costs, and the easiest place to make up for it is wages, since that is the biggest cost of organizations. The PPI is up +10% since the recovery started, while the CPI is up +4.6%. That disparity gets made up somewhere, and it's in operations. The increased productivity is paying for the increased materials costs.

Where does this lead? There's more muddling ahead. Most all economic forecasters have reduced their forecasts for Q2 and the rest of the year to be in the range of +2% (there were some forecasts of +4% earlier in the year by some of them). Look for forecasts to be revised yet again. On Friday, July 29, GDP for Q2-2011 will be released, but the Bureau of Economic Analysis will be revising their GDP and many other critical data series all the way back to 2003. The data will probably show that the recession was deeper than originally reported. Don't be surprised if the recovery is also downgraded.

Commentary & Analysis

The Recession and Recovery in Perspective

Last week'

Last week's consumer price index (CPI) and producer price index (PPI) showed that inflation has slowed down. Does it really matter? One of the problems with inflation measurements is that they do not allow you to judge whether or not the inflation is caused by shortages of goods or increased demand for goods. Nor do they take into account the additional productivity that might be related to those goods, such as our greater efficiency in the use of energy products. If gas prices rise to $4 today, it's not the same gas we had in 1980, because our cars today use that gasoline far more efficiently; it's the price per mile that's the more important measure than miles per gallon.

But that matters little; commodity prices are starting to rise again, and June's inflation pullbacks were probably temporary, until we have some kind of price collapse as we had in late 2008. Who knows when and even if that might come? When I lived on Long Island, there was a gun shop that gave away bumper stickers that said "Make love, not war, but be prepared for both," which, when translated to managerial strategy, is good advice.

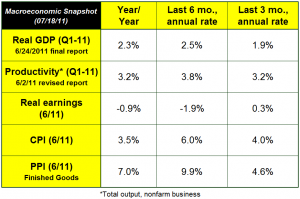

It's probably a better idea to focus on the beginning date of the recession, December 2007 and compare things to that time period. But before that, take a look at our current indicators on a year-to-year basis, and annualized 6-month and 3-month rates (click on table to enlarge).

The rates for the CPI and PPI for the last three months are now lower than the six month rates, but even though they are, they are beyond the targeted rates of the Federal Reserve. Real earnings, which is what's in people's paychecks after inflation, is finally showing a small rise, but it might as well be flat. Productivity is still higher than GDP, warning that employment growth will be minimal.

With this overview in mind, it's good to look at where we are since the declared start of the recession in December 2007. Remember, the start of a recession is the last peak of data. So that means that December 2007, or Q4-2007, was the last time things were going well. Since that time, GDP is up +0.6%, so it might as well be flat. Earnings are up +0.9%, which would mean that earnings are rising faster than economic growth, but it doesn't feel that way. Productivity is down -0.1% since that time. The CPI is up +7.4% and the PPI is up +12.4%. Essentially, everything is mainly flat, except for inflation. The cost of staying in the same place has gone up.

The recovery started in June of 2009. Recovery start dates are selected as the low point from the start of the recession. Since that time, GDP is up 5%. Productivity is up +6.6% (again, when productivity is greater than GDP, it implies employment contraction; employment rises when the economy grows faster than productivity). Even though GDP and productivity are up smartly since June 2009, real earnings are down -1.4%. This is why there is such concern for the economy and workers. Other than that there are not enough employed workers, current workers pay is not increasing commensurate with their output. Why? Higher materials prices are eating into business costs, and the easiest place to make up for it is wages, since that is the biggest cost of organizations. The PPI is up +10% since the recovery started, while the CPI is up +4.6%. That disparity gets made up somewhere, and it's in operations. The increased productivity is paying for the increased materials costs.

Where does this lead? There's more muddling ahead. Most all economic forecasters have reduced their forecasts for Q2 and the rest of the year to be in the range of +2% (there were some forecasts of +4% earlier in the year by some of them). Look for forecasts to be revised yet again. On Friday, July 29, GDP for Q2-2011 will be released, but the Bureau of Economic Analysis will be revising their GDP and many other critical data series all the way back to 2003. The data will probably show that the recession was deeper than originally reported. Don't be surprised if the recovery is also downgraded.

The rates for the CPI and PPI for the last three months are now lower than the six month rates, but even though they are, they are beyond the targeted rates of the Federal Reserve. Real earnings, which is what's in people's paychecks after inflation, is finally showing a small rise, but it might as well be flat. Productivity is still higher than GDP, warning that employment growth will be minimal.

With this overview in mind, it's good to look at where we are since the declared start of the recession in December 2007. Remember, the start of a recession is the last peak of data. So that means that December 2007, or Q4-2007, was the last time things were going well. Since that time, GDP is up +0.6%, so it might as well be flat. Earnings are up +0.9%, which would mean that earnings are rising faster than economic growth, but it doesn't feel that way. Productivity is down -0.1% since that time. The CPI is up +7.4% and the PPI is up +12.4%. Essentially, everything is mainly flat, except for inflation. The cost of staying in the same place has gone up.

The recovery started in June of 2009. Recovery start dates are selected as the low point from the start of the recession. Since that time, GDP is up 5%. Productivity is up +6.6% (again, when productivity is greater than GDP, it implies employment contraction; employment rises when the economy grows faster than productivity). Even though GDP and productivity are up smartly since June 2009, real earnings are down -1.4%. This is why there is such concern for the economy and workers. Other than that there are not enough employed workers, current workers pay is not increasing commensurate with their output. Why? Higher materials prices are eating into business costs, and the easiest place to make up for it is wages, since that is the biggest cost of organizations. The PPI is up +10% since the recovery started, while the CPI is up +4.6%. That disparity gets made up somewhere, and it's in operations. The increased productivity is paying for the increased materials costs.

Where does this lead? There's more muddling ahead. Most all economic forecasters have reduced their forecasts for Q2 and the rest of the year to be in the range of +2% (there were some forecasts of +4% earlier in the year by some of them). Look for forecasts to be revised yet again. On Friday, July 29, GDP for Q2-2011 will be released, but the Bureau of Economic Analysis will be revising their GDP and many other critical data series all the way back to 2003. The data will probably show that the recession was deeper than originally reported. Don't be surprised if the recovery is also downgraded.

The rates for the CPI and PPI for the last three months are now lower than the six month rates, but even though they are, they are beyond the targeted rates of the Federal Reserve. Real earnings, which is what's in people's paychecks after inflation, is finally showing a small rise, but it might as well be flat. Productivity is still higher than GDP, warning that employment growth will be minimal.

With this overview in mind, it's good to look at where we are since the declared start of the recession in December 2007. Remember, the start of a recession is the last peak of data. So that means that December 2007, or Q4-2007, was the last time things were going well. Since that time, GDP is up +0.6%, so it might as well be flat. Earnings are up +0.9%, which would mean that earnings are rising faster than economic growth, but it doesn't feel that way. Productivity is down -0.1% since that time. The CPI is up +7.4% and the PPI is up +12.4%. Essentially, everything is mainly flat, except for inflation. The cost of staying in the same place has gone up.

The recovery started in June of 2009. Recovery start dates are selected as the low point from the start of the recession. Since that time, GDP is up 5%. Productivity is up +6.6% (again, when productivity is greater than GDP, it implies employment contraction; employment rises when the economy grows faster than productivity). Even though GDP and productivity are up smartly since June 2009, real earnings are down -1.4%. This is why there is such concern for the economy and workers. Other than that there are not enough employed workers, current workers pay is not increasing commensurate with their output. Why? Higher materials prices are eating into business costs, and the easiest place to make up for it is wages, since that is the biggest cost of organizations. The PPI is up +10% since the recovery started, while the CPI is up +4.6%. That disparity gets made up somewhere, and it's in operations. The increased productivity is paying for the increased materials costs.

Where does this lead? There's more muddling ahead. Most all economic forecasters have reduced their forecasts for Q2 and the rest of the year to be in the range of +2% (there were some forecasts of +4% earlier in the year by some of them). Look for forecasts to be revised yet again. On Friday, July 29, GDP for Q2-2011 will be released, but the Bureau of Economic Analysis will be revising their GDP and many other critical data series all the way back to 2003. The data will probably show that the recession was deeper than originally reported. Don't be surprised if the recovery is also downgraded.

The rates for the CPI and PPI for the last three months are now lower than the six month rates, but even though they are, they are beyond the targeted rates of the Federal Reserve. Real earnings, which is what's in people's paychecks after inflation, is finally showing a small rise, but it might as well be flat. Productivity is still higher than GDP, warning that employment growth will be minimal.

With this overview in mind, it's good to look at where we are since the declared start of the recession in December 2007. Remember, the start of a recession is the last peak of data. So that means that December 2007, or Q4-2007, was the last time things were going well. Since that time, GDP is up +0.6%, so it might as well be flat. Earnings are up +0.9%, which would mean that earnings are rising faster than economic growth, but it doesn't feel that way. Productivity is down -0.1% since that time. The CPI is up +7.4% and the PPI is up +12.4%. Essentially, everything is mainly flat, except for inflation. The cost of staying in the same place has gone up.

The recovery started in June of 2009. Recovery start dates are selected as the low point from the start of the recession. Since that time, GDP is up 5%. Productivity is up +6.6% (again, when productivity is greater than GDP, it implies employment contraction; employment rises when the economy grows faster than productivity). Even though GDP and productivity are up smartly since June 2009, real earnings are down -1.4%. This is why there is such concern for the economy and workers. Other than that there are not enough employed workers, current workers pay is not increasing commensurate with their output. Why? Higher materials prices are eating into business costs, and the easiest place to make up for it is wages, since that is the biggest cost of organizations. The PPI is up +10% since the recovery started, while the CPI is up +4.6%. That disparity gets made up somewhere, and it's in operations. The increased productivity is paying for the increased materials costs.

Where does this lead? There's more muddling ahead. Most all economic forecasters have reduced their forecasts for Q2 and the rest of the year to be in the range of +2% (there were some forecasts of +4% earlier in the year by some of them). Look for forecasts to be revised yet again. On Friday, July 29, GDP for Q2-2011 will be released, but the Bureau of Economic Analysis will be revising their GDP and many other critical data series all the way back to 2003. The data will probably show that the recession was deeper than originally reported. Don't be surprised if the recovery is also downgraded.

About Dr. Joe Webb

Dr. Joe Webb is one of the graphic arts industry's best-known consultants, forecasters, and commentators. He is the director of WhatTheyThink's Economics and Research Center.

Video Center

- Questions to ask about inkjet for corrugated packaging

- Can Chinese OEMs challenge Western manufacturers?

- The #1 Question When Selling Inkjet

- Integrator perspective on Konica Minolta printheads

- Surfing the Waves of Inkjet

- Kyocera Nixka talks inkjet integration trends

- B2B Customer Tours

- Keeping Inkjet Tickled Pink

© 2024 WhatTheyThink. All Rights Reserved.