Let’s blame it all on a sixth-century monk named Dionysius Exiguus (literally, “Dennis the Short”). He was the one charged, by Pope Saint John I, to start counting actual chronological years or, specifically, the year of Jesus’ birth. Dennis began his chronology with the foundation of Rome, and ergo Jesus was born in the year 753 A.U.C. (that is, ab urbe condita or “from the foundation of the city”—Rome, natch). He then decided to restart everything a year later—and 754 A.U.C. became the year 1 A.D. (Anno Domini, year of the Lord). As anyone with any sense of the space-time continuum is aware (and this often excludes me), this is how we reckon our current years, decades, and centuries, for better or worse. The problem, you can see, is that the diminutive Dionysius didn’t include a year 0. This means that any given decade, century, or millennium technically doesn’t begin when the year rolls over from 9 to 0, but rather from 0 to 1. So when everyone was having all those Y2K millennium parties, it was actually on December 31, 2000, that everyone should have been partying like it was 1999.

Got it? Good.

I bring this up because as the calendar has changed over from 2009 to 2010—improbable as it may seem, for those of us who still haven’t quite become used to the fact that we are 10 years into the 21st century already (as Dionysis Exiguus would say, tempus fugit or, as they would perhaps say in Brooklyn, tempus fuggeddaboutit)—there have been the usual fin-de-decade best-of lists and countdowns, all of which are technically a year early. Or, since the 2000s began in 2000, maybe they’re not. Yes? No? Maybe? Norman, coordinate!

In an essay published five or so years prior to Y2K, one of my great intellectual heroes, the late great biologist Stephen Jay Gould, discussed this issue (see “Dousing Diminutive Dennis’ Debate [or DDDD=2000],” collected in Dinosaur in a Haystack, Harmony Books, 1995) in terms of “high culture” vs. “pop culture”:

...commentary has so far missed this important example from the great century debate. The distinction still mattered in 1900, and high culture won decisively by imposing January 1, 1901, as the inception of the twentieth century. Pop culture (or the amalgam of its diffusion into courts of decision-makers) may already declare clear victory for the millennium, which will occur at the beginning of the year 2000 because most people feel it so in their bones, Dionysius notwithstanding—and again I say bravo. [A] young friend wanted to resolve the debate by granting the first century only ninety-nine years.

Sure; why not? Dionysius was just making it up he went along, so why can’t we?

Whilst I am sure that there are those who will continue to argue that we are still in the “naughts” (or however we are referring to the first decade of the 21st century—and frankly I’d be perfectly in favor of never referring to it ever again), I think it best that we consider it over and move on.

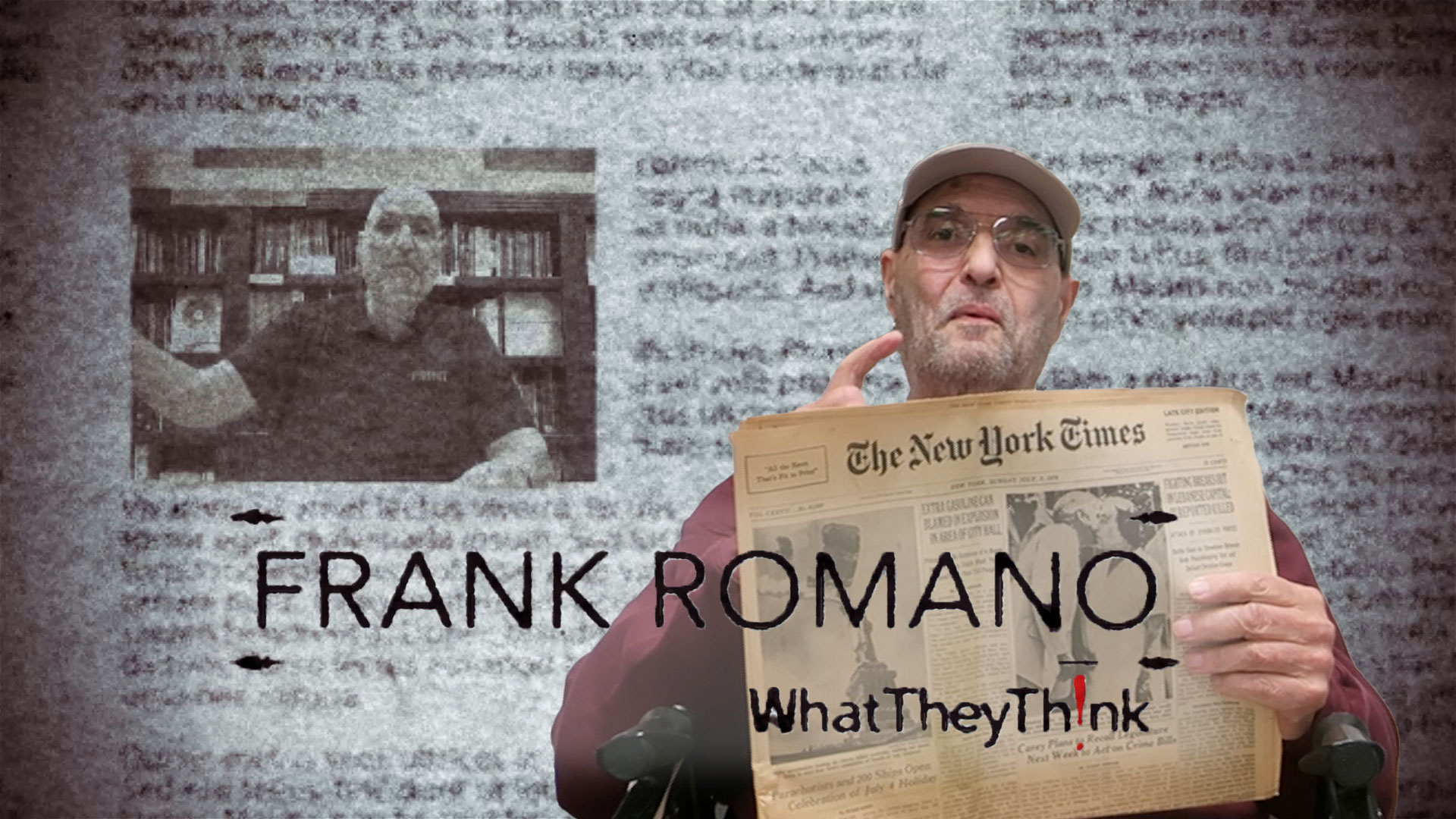

This is the basic theme of a new WhatTheyThink special report that Dr. Joe and I worked on, the January 2010 Quarterly Business Conditions Report.

As probably anyone in the printing industry can tell you, the “naughts” were just that—all for naught, quite possibly the worst decade the industry has ever seen. And it has very little to do with general economic conditions, although the Great Recession certainly didn’t help. Rather, we are an industry in transition, as our culture is moving away from printed to electronic communications. Not wholly, of course, but increasingly. We may not like it, but there it is. (As someone who was once forced, A Clockwork Orange-like, to sit through American Idol, I often find what’s popular to be rather baffling.) Anyway, the printing industry has yet to come to grips with these changes intellectually, much less strategically. In our Quarterly Business Conditions reports (published, cleverly enough, every quarter), in our Print and Creative Forecast 2010, and in other forthcoming reports this year, we offer some ideas and strategies. We look at where we’ve been, where we are now, where we’re going—and, most importantly, where we need to go.

The “naughts” represent a lost decade for the industry. Even if we’re technically a year early, perhaps it’s best to put those lost years behind us and charge into a new decade with optimism and actionable strategies to survive and thrive in the year(s) ahead.

Let’s try to make 2010 be a banner year for the printing industry—and not a John Banner year.

Discussion

Join the discussion Sign In or Become a Member, doing so is simple and free