At McNally Jackson Books, they call their new Espresso Book Machine (EBM) "this gleaming, gluing wonder," and the innovative in-store book manufacturing system certainly is all of that. But it's also an experiment in non-traditional publishing that just might represent the start of a new paradigm for bringing books to market, one independent bookseller and one print-on-demand title at a time.

Located on Prince Street in the stylish SoHo district of Manhattan, McNally Jackson Books acquired its EBM from the developer, On Demand Books, in January. The machine has been so busy since then that bookstore owner Sarah McNally can't give a precise count of the number of books it has produced.

Sarah McNally, owner, and Adjua Greaves, Espresso Book Machine (EBM) specialist, at McNally Jackson Books.

She's certain that the volume runs to "thousands and thousands" of titles, most of them by self-publishing authors. In-store book printing with the EBM isn't a major profit center for the bookstore yet, but McNally has high hopes that it could be-once mainstream book publishers realize that what she's doing isn't the competitive threat that some of them think it is.

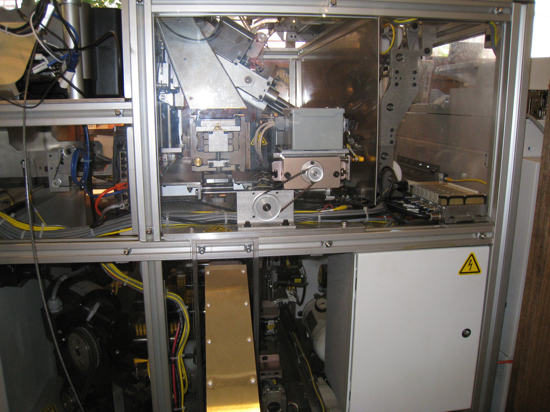

The EBM-an integrated suite of components for printing, binding, and finishing perfect-bound paperback books-occupies about 21 square feet of space in a high-traffic area on the store's main floor, where shelf-browsing customers can watch it in action. A collage in the window facing Prince Street invites passersby to come in and see the EBM for themselves.

Unique in New York

When they do, they will encounter the only Espresso Book Machine in New York City and one of just eight in operation at independent booksellers in the U.S. The worldwide installed base of EBMs comprises 45 locations, including a few with multiple machines. But, McNally had no qualms about being an early adopter: after consulting with other EBM-equipped bookstores, she says, the thought of bringing one to McNally Jackson Books "didn't feel that risky."

The Espresso Book Machine is the brainchild of publisher emeritus Jason Epstein, who with On Demand Books co-founders Dane Neller and Thor Sigvaldason began installing the first units in 2006. Besides independent booksellers, EBM locations include libraries, chain and university bookstores, and other retail outlets.

On Demand Books calls its multi-patented system an "ATM for books" that can produce perfect-bound paperbacks with full-color covers at a production cost, according to the company, of a penny a page.

The workflow is entirely digital. The EBM's EspressNet software links to copyrighted material from publishers affiliated with POD book printer Lightning Source, including Hachette, McGraw-Hill, Simon & Schuster, WW Norton, Macmillan, and John Wiley. Books in the public domain are obtained through arrangements with Google and various Internet repositories. All told, this gives EBM owners access to more than four million printable titles, according to On Demand Books.

Xerox Likes the Idea

Last year, Xerox voted confidence in the in-store book printing concept by partnering with On Demand Books to sell, lease, and service the EBM in a configuration built around its 4112 copier/printer. This version of the EBM, exhibited by Xerox at Graph Expo 2010, is the model installed at McNally Jackson Books.

The production sequence, controlled from a built-in EspressNet interface by either of two EBM operators that the bookstore now employs, begins with the printing of black-and-white, letter- or A4-sized book blocks on the 110-ppm Xerox 4112 while an eight-cartridge Epson inkjet printer simultaneously prints the covers in color. The interior pages can be imaged at up to 1,200 x 1,200 and, for halftones, at up to 2,400 x 2,400 dpi (equivalent to150 lpi in high-quality mode.)

The book blocks are accumulated, clamped, milled on the binding edge, glued with hot-melt adhesive, and pressed to the covers. Trimming on three sides follows, and the finished, perfect-bound books are delivered spine first by the EBM.

Built around a Xerox 4112 copier/printer, the Espresso Book Machine can print, bind, trim, and deliver a paperback book up to 800 pages in five minutes.

The entire robotic process-much of it observable through the machine's clear front panels-takes about five minutes. Books can be queued for automatic production, and, other than removing finished books from the delivery, no operator intervention is needed once the sequence has been initiated.

Book formats can be from 4.5" x 5" to 8" x 10"; trim sizes within this range are infinitely variable. The EBM can bind thicknesses up to 800 pages (the minimum page count is 40). Input files for text and covers are strictly PDF: "that means no .doc, .txt., .rtf, or any other alphabet soup," the bookstore's printing guidelines say.

Don't Mind Us-We're Just Printing

Despite all of the mechanical activity that takes place while the machine is running, production is quiet, and there are no detectable odors from the hot-melt glue simmering at 350ºF inside. During a recent visit, readers seated in an adjacent nook didn't appear to mind-or even to notice-that the EBM was being put through its paces. The device seemed to fit as naturally into the ambience of the bookstore as the coffee bar or the checkout counter.

What's been coming out of the EBM has come as something of a surprise to McNally, who opened the bookstore in 2004. Given New York's large and book-hungry university population, she initially expected most of the demand to be for out-of-print titles.

However, her best EBM customers have turned out to be authors who either can't find conventional publishers or simply prefer to do it themselves. Word about the gleaming, gluing wonder in SoHo has spread fast among these content creators: "We get a new self-publisher almost every day," McNally says. Their works range widely in genre and subject matter, from science fiction and poetry collections to a catalog of do-it-yourself projects and a scholarly dissertation titled, "Abraham Lincoln Was A Witch."

But, just because a book is self-published doesn't mean that its author won't need professional help with the details of getting the title into production. Stepping somewhat beyond the role of printer, McNally Jackson provides this kind of assistance with two low-cost packages of publishing services for authors who use the EBM.

The $100 plan includes file conversion advice, preflight, cover layout, access to freelance designers and editors, and file retention for reruns. There's also a one-time, no-frills option for $15 and an a la carte list of services such as ISBN registration and interior page design.

Prices for Self-Publishers

When files are ready to print-usually after review in one to two business days-the bookstore's EBM customers pay a setup fee of $6 and $0.02 per page. The customer's cost to produce a 100-page book, for example, would be $8: $6 plus (100 x .02). McNally Jackson offers discounts for bulk printing, and it has a print-on-demand consignment program for self-publishers who opt to sell their works in the bookstore.

Cover prices for self-published books are up to the originators. Prices for books sourced from publishing houses and Google follow page-count-based schedules set by those providers. In most cases, says McNally, a book produced in-store on the EBM can be sold for about the same amount of money as a comparable book printed by a publisher.

Self-publishers have generated most of the volume on McNally Jackson's EBM since it was installed at the beginning of the year.

McNally says that her EBM is running at better than break-even and that the machine was "profitable almost immediately" after she put it in. She sees additional opportunities for EBM bookstores in community-service publishing and in creative applications such as the book-length marriage proposal that a hopeful suitor recently printed on her machine.

In McNally's opinion, in-store book printing is a business model whose time has come. "There has been a lot of media for the machine," she says, referring to trade- and general-media reporting about the EBM. "It really looks like it's at a tipping point."

She acknowledges, though, that to some publishers, the tipping point may look more like the edge of a cliff to back away from.

Fearing Fear Itself?

Their reluctance, she says, stems from two concerns. One is data security: the fear of what might happen to book files as they move about the EBM network. (On Demand Books says that the network uses industry-standard cryptography to provide secure communications. The EspressNet software is said to track content movement and order processing with "fine-grained visibility" at every stage.)

Publishers also worry, according to McNally, that booksellers will find in-store printing such an economically attractive proposition that they'll order and stock fewer copies from traditional channels. But the idea that booksellers can get superior profit margins from printing in-copyright books on the EBM is "patently not true," she says.

Her costs to operate McNally Jackson's EBM include dual leasing arrangements with On Demand Books and Xerox; fees payable to the content providers; and the usual overhead associated with running production equipment. The resulting pressure on EBM book margins means, she says, that publishers needn't fear her as a competitor in the printing space.

Their misgivings may be fading. McNally says that two of the largest publishing houses have "theoretically agreed" to open their backlists to printing on her EBM. When they do, and if other publishers follow suit, "it would raise our sales enormously."

And not just at McNally Jackson Books. Given the opportunity to mine a universe of content for on-demand production on the Espresso Book Machine, "there's no bookseller who can, who won't," McNally says.

Discussion

Join the discussion Sign In or Become a Member, doing so is simple and free