On November 25, 1915, Albert Einstein submitted the final draft of his field equations for the general theory of relativity to the Royal Prussian Academy of Sciences in Berlin. One hundred years later, the work continues to predict the inner workings of space, time, gravity, and every other force that makes the universe the universe.

One thing its creator probably didn’t anticipate was that the fame of the general theory of relativity would make his face and form among the most widely reproduced graphic images ever.

Even to those who don’t know who Einstein was or what his achievements consisted of, the crown of white hair and the benign, bemused expression stand for science in a way that no other symbols do. To graphic artists, the power of that identification has been an irresistible source of inspiration in fine art, pop culture, and commercial interpretations.

This woodcut of Einstein by Antonio Frasconi was commissioned by the Princeton Print Club in 1952 and now belongs to the National Portrait Gallery of the Smithsonian Institution. It isn’t available for sale in reproduction, but thousands of other portraits are—online sources like this one have turned Einsteinian imagery into an industry.

Andy Warhol, who always knew a high-profile graphic opportunity when he saw one, included the father of relativity in his silkscreen series Ten Portraits of Jews of the Twentieth Century. As pictures of Einstein became popular, they also became marketable—so much so that 58 years after his death in 1955, Forbes made a place for him in its list of “The Top-Earning Dead Celebrities” of all time.

Einstein’s globally known appearance was catnip to advertisers and marketers, and that sometimes upset the legal equation. In 2009, when General Motors transplanted his head onto a ripped and buff male body for an ad promoting an SUV, the owner of Einstein’s image pushed back with a lawsuit. The plaintiff was Hebrew University of Jerusalem, to which Einstein had bequeathed the rights to publicity and commercial licensing.

But, A U.S. District Court would rule that the rights had already expired in 2005, 50 years after the physicist’s death—and that the expiration served the public interest of free expression. As the court put it, “Einstein is thoroughly ingrained in our cultural heritage and that at some point needs to be available for expression and not just as a possession, even for tasteless ads.”

For as long as the general theory of relativity continues to hold sway as the key to understanding the cosmos, probably so will Einstein’s appeal as an icon for selling things.

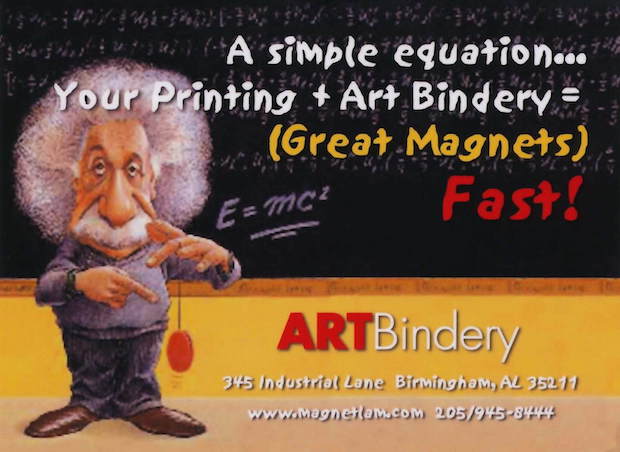

Those who remember Egghead Software, the chain “e-tailer” of applications during the years when applications still came in packages, will also remember its familiar-looking mascot. In a 2000 Pepsi commercial, a dead ringer for the great man called the choice between that soft drink and Coca-Cola “a no-brainer.” The illustration above this post shows that in this industry, too, Einstein enjoys cred as a pitchman.

Needless to say, books have always been vehicles for conveying images of Einstein—and of what his work looked like as he originally published it. For example, collectors can buy or bid for this first-edition offprint of The Foundation of the Generalised Theory of Relativity from 1916. (An offprint is a printed copy of an article that originally appeared as part of a larger publication.)

Princeton University, where Einstein worked and taught from 1933 until his death in 1955, has published a facsimile of the work’s original handwritten manuscript with annotations and an English translation. Princeton and others have partnered with Hebrew University to produce the Digital Einstein Papers, a compendium of 30,000 documents with links to additional materials at Hebrew University’s Einstein Archives Online.

Aimed at young readers—and probably less intimidating than the Princeton publications for grown-up readers who aren’t scholars—is this graphic biography of Einstein from Saddleback Press. And, for those who want to skirt the scholarship altogether and just engage creatively with the man and his image, there is this downloadable coloring page from Crayola.

What would Einstein have made of being transfigured from a slightly eccentric-looking intellectual into one of modern history’s most recognizable, evocative, and beloved visual symbols? Probably none of it would have troubled him—not even the beefcake ad—because he would have seen in it something of his own method for teasing out the hidden mechanics of time and space.

“To stimulate creativity,” he once said, “one must develop the childlike inclination for play and the childlike desire for recognition.” By playing endlessly and respectfully with his image, graphic illustrators have helped in no small way to bring Einstein and his body of work the universal recognition they command.

Discussion

Join the discussion Sign In or Become a Member, doing so is simple and free