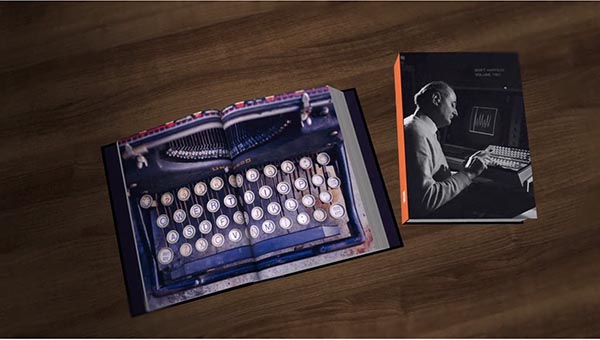

Shift Happens

There have been books about the history of the typewriter, the Linoytype, phototypesetting, even desktop publishing, but there has yet to be written a history of the keyboard (although Frank my beg to differ). Now, a new book aims to change that. Marcin Wichary is a design manager who has written and is Kickstarting a book called Shift Happens.

Keyboards fascinated me for years. But it occurred to me that a good, comprehensive, and human story of keyboards – starting with typewriters and ending with modern computers and phones – has never been written. How did we get from then to now? What were the steps along the way? And how on earth does QWERTY still look the same now as it did 150 years ago? I wanted a book like this for years. So I wrote it.

Told in two volumes and lavishly illustrated, it has more than quadrupled its Kickstarter goal.

The book contains over 1,300 photos, including both historical photographs of keyboards in use (some really hard to find!), as well as modern, beautiful photos of all kinds of keyboards. I carefully considered the inclusion and appearance of every picture (here’s one example), and more than 1/3 photos appearing in “Shift Happens” were taken exclusively for this book by me and others.

Check out the book’s website here. Take a 3D tour of the book here.

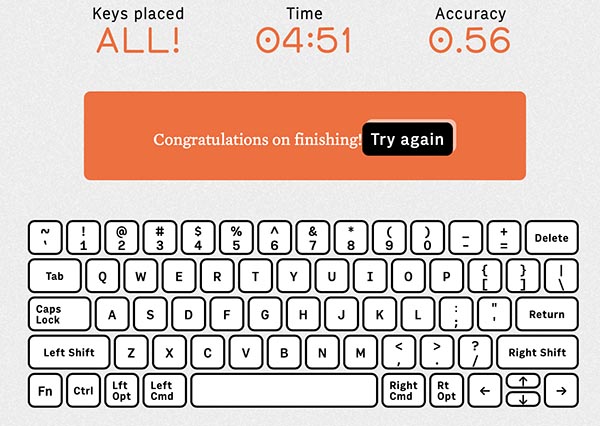

And play the interactive game “Can you arrange a keyboard from memory?” here. It’s harder than you’d think!

Parts is Parts

If, by the way, you happen to own a typewriter—an old school one—you may have trouble finding parts to keep it in working order. However, if you have access to a 3D printer, head on over to 3Dtypewriterparts.com and see if you can print downloadable 3D printable files of the parts you need, from a variety of different makes and models.

If you need parts for your 3D printer, sorry, can’t help.

The Sensitive Type

Via Print magazine, here is a new phrase to conjure with: “type empathy.” Say what?

That is, the ability to widen the lens—historically, culturally, orientationally—on how we teach typography and create it. Can we further our awareness and create more meaningful dialogue with one another through more diverse typography choices?

That’s a big ask for typography. How does that work in practice?

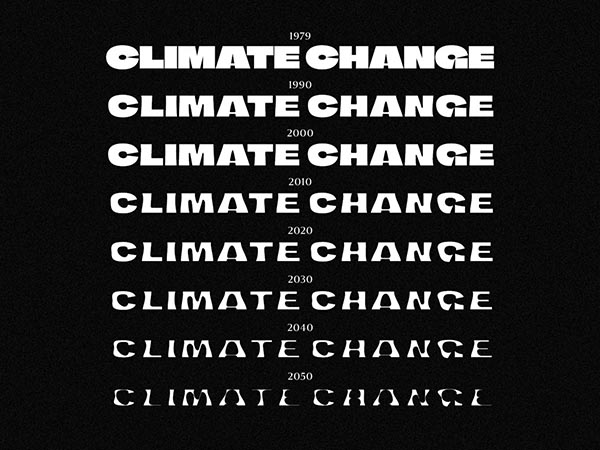

Our world faces catastrophic issues that need attention. As global warming viciously plays out, it’s not enough to visualize its disasters in tidy, bold headlines, as the Nordic region’s largest newspaper, Helsingin Sanomat, discovered. Working with Eino Korkala and Daniel Coull, the team created Climate Crisis Font based on Arctic Sea ice data. The heaviest font-weight represents the Arctic sea ice in 1979, while the lightest—mere amoebic slivers—represents the IPCC’s 2050 forecast when that same ice will shrink to 30% of its 1979 mass. The typeface provides a window into our bleak future—unless we act.

Classical type is making way for a more nuanced type that not only carries what we are saying but how it’s said and who is saying it. It’s not only condensed, all-cap, bold type (which we adore) shouting into the air — type is creating a new dialogue.

Marginal Notes

If you’re like us, and we know we are, you sometimes write in books. Not necessarily in novels, but sometimes in non-fiction we’ll highlight or underline certain passages or add various comments to the text. This has been going on for as long as there have books, and, via the BBC, researchers are now starting to focus their attention on ancient book doodles.

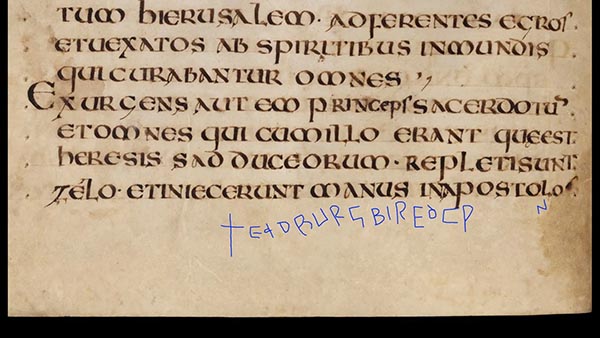

Around 1,300 years ago, a woman leant over a precious book, and etched some letters into the margin, along with some cartoonish drawings. She didn’t use ink – she scratched them in, so they were almost invisible to the naked eye.

The 8th-Century book – a copy of the Act of Apostles [sic] from the Christian New Testament – is now kept in the Bodleian Library in Oxford. Researchers have known for a while that the religious text was probably owned by a woman, but they weren't sure who.

In 2022, the researcher Jessica Hodgkinson at the University of Leicester decided to take a closer look, and was surprised to find a hidden etching on page 18, just below the Latin text.

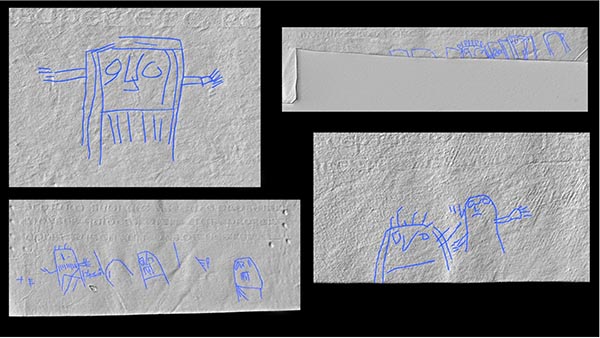

When digitally highlighted, it looked like this:

Credit: Archiox/Bodleian Library

What could it mean? The first symbol is pretty obviously a cross, with the next set of letters spelling out “Eadburg,” which Hodgkinson is pretty certain is the name of the book’s owner, and she’s fairly certain she was a nun. It had also been scratched into four other pages.

The subsequent letters were a bit more enigmatic: could it mean “bears cwærtern” – the Old English word for “prison”? The Latin passage it accompanies describes the imprisonment of the Apostles, so Eadburg might have been drawing a parallel with her own situation.

On several other pages, Hodgkinson and her colleagues found drawings of little people—a square figure with outstretched arms looking not unlike Spongebob Squarepants, a person holding their hand in the face of a companion, and others.

Credit: Archiox/Bodleian Library

The Archiox researchers use two devices to create digital representations of pages and objects: the “Selene”, which has four cameras capable of capturing differences in surface relief down to 25 micrometres (0.025mm/0.001in), and the “Lucida”, which deploys lasers and two tiny cameras to create 3D scans.

They are using this technology to uncover previously hidden doodles and other marginalia in other books in the Bodleian’s collection—and even on centuries-old copper printing plates. No one knows why people made these notes or doodles.

[Adam Lowe, founder of the Factum Foundation in Madrid, a non-profit which engineered the technology for the Bodleian as part of the Archiox project] suggests that through this new approach, there could be thousands of new discoveries waiting to be made, hidden in plain sight in libraries and art collections. “People are starting to realise that ‘relief information’ is transforming our knowledge. There must be objects in libraries all over the world that could benefit from this technology…it's about treating material objects as evidence,” he says. “There’s a lot that’s known, but there’s a lot more that can be, and I think that's an incredibly inspiring and exciting thought.”

Post Parade

Emily Post, that is. The COVID pandemic (or, actually, the 21st century) threw a monkey wrench into what we think of acceptable behavior or proper etiquette. How do we behave in certain circumstances, online or off? New York magazine is here to help, because when you think of proper etiquette, you immediately think of New York.

We’ve enjoyed a global pandemic, open employer-employee warfare, a multifront culture war, and social upheavals both great and small. The old conventions are out (we don’t whisper the word cancer or let women off the elevator first anymore, for starters). The venues in which we can make fools of ourselves (group chats, Grindr messages, Slack rooms public and private) are multiplying, and each has its own rules of conduct. And everyone’s just kind of rusty. Our social graces have atrophied.

It seems like had before, but fine, premise granted.

We asked people instead what specific kinds of interactions or situations really made them anxious, afraid, uncertain, ashamed. From there, we created rigid, but not entirely inflexible, rules.

Then we took our own medicine — we implemented these rules in our professional and personal lives. Some really didn’t work. (“It’s been great to chat” didn’t quite land when we used it as a way to exit a boring conversation at a holiday party.) Others felt like instant canon (we agreed, for example, that text-message amnesty is granted after 72 hours). We fine-tuned and eliminated. We talked to friends, entertaining experts, and service workers. We sparked office arguments and made messes and ended up with a guide that we hope will stand the test of at least a bit of time — until the next great exciting social upheaval.

It’s voluminous and comprehensive guide, only a fraction of which will be relevant (and some we just didn’t understand). Click through if you want to know what Emily Post would say if she were on TikTok.

Graphene Goes Kayaking

Was it a good week for graphene news? It’s always a good week for graphene news! Graphene is being used to create stronger and lighter composite kayaks. From (who else?) Graphene-Info:

Haydale has announced that its bespoke mechanical graphene masterbatch has been used to create stronger and lighter composite sea kayaks for Norwegian paddle sport brand Norse Kayaks ("Norse").

Using the new graphene-enhanced material has reportedly made the Norse kayak 30% lighter, going from 23kg to 16kg, making the composite kayak easier to load and transport. The use of graphene in the vacuum infusion composite layup process has also increased both impact strength and stiffness, improving the resistance to breakage in critical areas of the kayak. Vibration dampening has also improved the user experience.

“Either This Man Is Dead or My Watch Has Stopped”

One recent feature incorporated into devices like iPhones and Apple Watches is the ability to detect car crashes and automatically call 911. Sounds like a useful feature, right? Well… Via the NY Times:

But the latest innovation appears to send the device into overdrive: It keeps mistaking skiers, and some other fitness enthusiasts, for car-wreck victims.

Lately, emergency call centers in some ski regions have been inundated with inadvertent, automated calls, dozens or more a week. Phone operators often must put other calls, including real emergencies, on hold to clarify whether the latest siren has been prompted by a human at risk or an overzealous device.

… The problem extends beyond skiers. “My watch regularly thinks I’ve had an accident,” said Stacey Torman, who works in London at Salesforce and also teaches spin classes. She might be safely on the bike, exhorting her class to ramp up the energy, or waving her arms to congratulate them, when her Apple Watch senses danger.

“I want to celebrate, but my watch really doesn’t want me to celebrate,” she said. Oh great, she thinks, “now my watch thinks I’m dead.”

Wait until the phones and watches themselves can determine who lives and who dies.

Waiting for the UFOs

A recent headline in the Washington Post stated the blatantly obvious: “We don’t know what UFOs Are.” Well, you know, we wouldn’t. If we did, they wouldn’t be “unidentified” flying objects, now would they? In a related story, via Business Insider, several years ago, Chinese spy balloons had been classified as UFOs. It’s also interesting that the DOD is phasing out the term “UFO.”

In December, the Department of Defense established the All-domain Anomaly Resolution Office to identify “unidentified anomalous phenomena” — in space, in the air, on land, or in the sea — that may threaten national security. The term UAP replaces the traditional “unidentified flying object” or UFO designation, as officials expect to evaluate anomalies “across all domains.”

Jurassic Park II: Dead as a Dodo

Via Scientific American, a company called Colossal Biosciences has announced plans to “de-extinct” the dodo (their term—you just can’t do that to the English language). They have seven secured $150 million in funding to do so. But is it feasible?

In 2002 [Beth Shapiro, lead paleogeneticist and a scientific advisory board member at Colossal Biosciences] published research in Science describing how her team had extracted a tiny piece of the bird’s mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA)—the DNA inside little organelles called mitochondria that gets passed down from mother to offspring. That snippet of mtDNA showed the dodo’s closest living relative was the Nicobar pigeon. Then, in 2022, Shapiro announced that her team at U.C. Santa Cruz had reconstructed the dodo’s entire genome.

Reconstructing a genome is one thing. Getting a living entity, that’s quite another.

Technically, a species could be resurrected by cloning DNA from a remnant cell. In reality, this has been impossible to achieve, mostly because viable DNA cannot be found. Most de-extinction programs aim to re-create a proxy of an extinct animal by genetic engineering, editing the genome of a closely related living species to replicate the target species’ genome. The edited genome would then be implanted into an egg cell of that related species to develop.

That’s when the real problems start.

The process must ensure that development proceeds correctly, that the animal is born successfully, that suitable surrogate parents nurture the creature, that it is administered a nutritious diet and that it is raised in an appropriate environment.

Which probably won’t be easy for a species that has been extinct for nearly 400 years. But even then:

With mammals, the process is like that used in the creation of Dolly the sheep, the world’s first animal to be cloned successfully from adult cells. But, Shapiro says, “we can’t clone birds.” Cloning requires access to an egg cell that is ready for fertilization but not yet fertilized. “There is no access to a bird egg cell at the same developmental time as there is for a mammal,” she explains. Colossal Biosciences is exploring a process to extract avian primordial germ cells (PGCs) from bird eggs. If the process works, PGCs from pigeons would be manipulated to eventually develop into a dodolike bird.

The big question is, why do this in the first place? Species can’t exist without an appropriate ecosystem—that’s why they go extinct: their environment changed and they failed to adapt. Bringing them back seems a little cruel. Still, it may make for an interesting remake of Jurassic Park.

“Water Me Now!”

Artist and educator David Bowen has created what we presume is an art installation comprising a machete-wielding philodendron. We kid you not:

This installation enables a live plant to control a machete. plant machete has a control system that reads and utilizes the electrical noises found in a live philodendron. The system uses an open source micro-controller connected to the plant to read varying resistance signals across the plant’s leaves. Using custom software, these signals are mapped in real-time to the movements of the joints of the industrial robot holding a machete. In this way, the movements of the machete are determined based on input from the plant. Essentially the plant is the brain of the robot controlling the machete determining how it swings, jabs, slices and interacts in space.

Cool idea for a murder mystery…

Bear It All

Recently, a bear discovered a wildlife camera that we use to monitor wildlife across #Boulder open space. Of the 580 photos captured, about 400 were bear selfies.?? Read more about we use wildlife cameras to observe sensitive wildlife habitats. https://t.co/1hmLB3MHlU pic.twitter.com/714BELWK6c

— Boulder OSMP (@boulderosmp) January 23, 2023

Endless Pastabilities

Last month, we linked to the tragic news that Ronzoni was discontinuing its Pastini (hmm…WhatTheyThink’s “Search News by Company” feature does not include Ronzoni; who do we see about that? Oh, right…). Anyway, we have better news on the pasta front this week: pasta maker Sfoglini is adding three new pasta shapes. Food & Wine has the lowdown:

Pasta manufacturer Sfoglini is teaming up with The Sporkful Podcast creator and host Dan Pashman to add three likely-new-to-you pasta shapes to your pantry. The two existing shapes hitting the brand’s roster are quattrotini and vesuvio — fun to look at, fun to wrangle on your fork, and fun to eat. The third is a new shape designed by Pashman himself, called cascatelli.

Because we are on top of all the latest pasta news, we have linked to cascatelli before. As for quattrotini, that comprises four tubes connected by a four-sided rectangle and is apparently served once a year during Carnival in a small region of Sicily. The new version includes some sauce-grabbing ridges.

The second shape, vesuvio, was named for its likeness to Mount Vesuvius. Short, round, and anchored by a large base that tapers to a thin cone, sauce collects into the spirals promising a perfect bite every time. This shape can be found in towns around the volcano it was named for, though it’s very hard to find in the U.S.

You have to be careful because vesuvio can erupt without warning and douse your kitchen with pasta sauce.

Left to right: quattrotini, cascatelli, and vesuvio. That looks like Mount Vesuvius?

If you want to give them a try, get thee to Sfoglini’s website.

Did anything catch your eye “around the Web” this week? Let us know at [email protected].

This Week in Printing, Publishing, and Media History

February 6

AD 60: The earliest date for which the day of the week is known. A graffito in Pompeii identifies this day as a dies Solis (Sunday). In modern reckoning, this date would have been a Wednesday.

1515: Italian publisher, founded the Aldine Press Aldus Manutius dies (b. 1449).

1756: American colonel and politician, 3rd Vice President of the United States Aaron Burr born. Wait for it.

1945: Jamaican singer-songwriter and guitarist Bob Marley born.

February 7

1497: In Florence, Italy, supporters of Girolamo Savonarola burn cosmetics, art, and books, in a “Bonfire of the vanities.”

1812: English novelist and critic Charles Dickens born.

1885: American novelist, short-story writer, playwright, and Nobel Prize laureate Sinclair Lewis born.

1898: Émile Zola is brought to trial for libel for publishing J'Accuse…!.

1997: NeXT merges with Apple Computer, starting the path to Mac OS X.

February 8

1587: The death of Mary, Queen of Scots (b. 1542).

1828: French author, poet, and playwright Jules Verne born.

1834: Russian chemist and academic, and creator of the Periodic Table of Elements Dmitri Mendeleev born.

1915: D. W. Griffith’s controversial film The Birth of a Nation premieres in Los Angeles.

1922: United States President Warren G. Harding introduces the first radio set in the White House.

1946: The first portion of the Revised Standard Version of the Bible, the first serious challenge to the popularity of the Authorized King James Version, is published.

1971: The NASDAQ stock market index opens for the first time.

1978: Proceedings of the United States Senate are broadcast on radio for the first time.

February 9

1737: English-American philosopher, author, activist, and pamphleteer Thomas Paine born.

1870: US president Ulysses S. Grant signs a joint resolution of Congress establishing the U.S. Weather Bureau.

1881: Russian novelist, short story writer, essayist, and philosopher Fyodor Dostoyevsky dies (b. 1821).

1923: Irish rebel, poet, and playwright Brendan Behan born.

1964: The Beatles make their first appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show, performing before a record audience of 73 million viewers across the US.

1986: Halley’s Comet last appeared in the inner Solar System.

February 10

1890: Russian poet, novelist, literary translator, and Nobel Prize laureate Boris Pasternak born.

1898: German director, playwright, and poet Bertolt Brecht born.

1940: Tom and Jerry make their debut with the cartoon Puss Gets the Boot.

1962: Roy Lichtenstein’s first solo exhibition opens. It includes Look Mickey, which featured his first use of Ben-Day dots, speech balloons, and comic imagery sourcing, all of which he is now known for.

1967: American director, producer, and screenwriter Vince Gilligan born.

1996: IBM supercomputer Deep Blue defeats Garry Kasparov in chess for the first time.

2005: American actor, playwright, and author Arthur Miller dies (b. 1915).

February 11

1650: French mathematician and philosopher René Descartes dies (b. 1596). Guess he didn’t think.

1800: English photographer, politician, and inventor of the calotype Henry Fox Talbot born.

1840: Gaetano Donizetti’s opera La fille du régiment receives its first performance in Paris, France.

1843: Giuseppe Verdi’s opera I Lombardi alla prima crociata receives its first performance in Milan, Italy.

1847: Thomas Edison born.

1909: American director, producer, and screenwriter Joseph L. Mankiewicz born.

1938: BBC Television produces the world’s first ever science fiction television program, an adaptation of a section of the Karel ?apek play R.U.R., that coined the term “robot.”

February 12

1804: German anthropologist, philosopher, and academic Immanuel Kant dies (b. 1724).

1809: English geologist and theorist Charles Darwin born.

1809: Sixteenth U.S. President Abraham Lincoln born.

1885: German publisher and founder of Der Stürmer Julius Streicher born.

1924: George Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue receives its premiere in a concert titled “An Experiment in Modern Music,” in Aeolian Hall, New York, by Paul Whiteman and his band, with Gershwin playing the piano.

1948: American computer scientist and engineer Ray Kurzweil born.

1950: English singer-songwriter, guitarist, and producer Steve Hackett born.

1994: Four thieves break into the National Gallery of Norway and steal Edvard Munch’s iconic painting The Scream.

Discussion

Join the discussion Sign In or Become a Member, doing so is simple and free