As 2012 winds down, how well has the printing industry learned to manage its ongoing consolidation through strategically executed mergers and acquisitions? It's a question that constantly occupies Paul Reilly, founding partner of New Direction Partners (NDP), an advisory firm to printers seeking to secure their futures through M&As.

The picture he sees is a mixed one. Although the pace of dealmaking is picking up, says Reilly, "we're not seeing any new buyers." There's little interest in acquiring printing companies, he explains, by anyone who is not already in the market and looking for opportunities to buy.

Transactions based on multiples of EBITDA-the type of deal most desired by sellers-also are on the rise, and the general pickup in business as the recession fades might appear to be cause. But, there's really no evidence of that, either, according to Reilly, who thinks that better management, not the economy, is what's chiefly responsible for making well-run printing companies more attractive as acquisition targets.

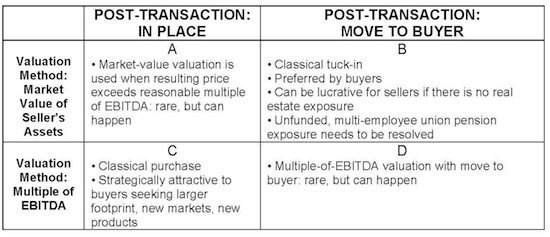

The chart below outlines the kinds of deals that Reilly says printers can expect to negotiate as they plan to acquire other firms or become candidates for acquisition themselves. The scheme consists of four possible outcomes determined by two sets of choices: the method of valuation to be used; and the disposition of the acquired company after the transaction is complete.

The most prevalent types of deals, says Reilly, will be found in the northeast and southwest corners of the chart-B and C, respectively-where the rewards to buyers and sellers can be highest. In B, the seller will be acquired through a tuck-in and will cease to operate as an independent entity. The "classical purchase" in C is based on EBITDA valuation and assumes that the acquired plant will continue to run and produce on its own.

A tuck-in takes place when one firm acquires selected assets and the book of business from another firm and the seller is paid in the form of an earn-out based on future sales. Buyers like tuck-ins because they bring opportunities both for growth and for cost reductions without the need for a large amount of up-front cash. Tuck-ins can be especially lucrative to sellers who have no real estate encumbrances-long-term leases or remaining mortgage payments-and can liquidate equipment and other assets that are not included in the deal.

Tension from Pensions

But, says Reilly, buyers should be cautious about acquiring companies whose employees are covered by a pension plan, especially if the pension plan is tied to a union contract. Such plans, he says, tend to be underfunded, leading to problems in the longer term when employees start to retire. Additionally, exiting a union pension plan to replace it with another may legally require a hefty liability payment to the union.

In a few cases that NDP has seen, says Reilly, the size of the payment actually exceeded the value of the company to be acquired, killing the deals. Fortunately, he adds, "in our experience, the amount of this liability is negotiable."

The "classical purchase" based on EBITDA and continued operation in place (area C on the chart) is a good strategy for companies that want a bigger or footprint or are seeking ready-made entry into new markets such as wide-format output or packaging. However, nothing prohibits closing down and absorbing the assets of a company acquired in this way (area D), and Reilly notes that EBITDA-based deals using this approach have occasionally been known to occur.

The size of the multiple of EBITDA (earnings before interest, tax, depreciation, and amortization) that determines the purchase price depends on the nature of the company being acquired and the growth trend of the segment it belongs to. The current range, according to Reilly, goes from 3 for general commercial printing firms to 5-plus for large firms and those with specialties that differentiate them.

Multiples: Not What They Were

A conservative expectation is best, says Reilly, noting that just a few years ago, the top end of the range was 6. Today, the multiples estimated for the industry's largest and strongest publicly traded firms-R.R. Donnelley, Consolidated Graphics, and Quad Graphics-come in at only a few tenths of a point above or below 4. Not much upward movement in EBITDA multiples is likely for the time being, Reilly says.

That partially accounts for an increase in the number of M&As based not on EBITDA but on the market value of the seller's assets (areas A and B). When a price calculated this way exceeds a figure that can reasonably be expected as a multiple of EBITDA, the deal is better for the seller. Companies can be acquired in place on this basis, but that outcome, according to Reilly, is relatively rare-businesses that cannot command respectable EBITDA multiples typically are not profitable enough to continue in independent operation post-sale.

Reilly asks printers to ask themselves which quadrant of his M&A matrix they would occupy if they had to make a deal tomorrow-a thought experiment that can help them to identify where strategic adjustments are needed. He recommends making a frank and realistic assessment of the options that most printers, sooner or later, will have to choose among as the next chapters for their companies.