It’s not tax reform unless it becomes law. There are differences between the House and Senate bills that are narrow enough for reconciliation and passage to look definite. Reform can make a big economic difference, but a lot has to do with timing.

Because of the Congressional Budget Office scoring of bills in a “give with one hand, take away with another” spirit, and their inability, by law, to use dynamic scoring that takes into account historical economic behavior, the reconciliation process can become difficult. Logic and economics can take quite a beating.

The Senate version does not lower the corporate tax rate until 2019, while the House does it for 2018. The belief, using CBO rules, is there will be $100 billion in tax revenue “saved” in 2018 by delaying the new rate. Really? All that would do is have businesses pile on their 2018 expenses, even with expenses that would more naturally occur in 2019. Then, they would push taxable profits into 2019. This can be done simply, especially at the end of the year – does no one think that some vendors in November 2018 will say to best customers “we’ll bill you in 2019”? If a corporation is in the 35% bracket and they know it’s going to 20%, that means each marginal dollar of profit for those few days almost doubles. That’s worth waiting 45 days for. Someone who has never heard the phrase “net present value” can figure this one out. They won’t preserve $100 billion in tax collections; they may actually plummet! We could get a “paper recession” because of the way that GDP is calculated. It is likely that the reconciliation with go with the House bill and make the 20% rate effective in 2018. If it does not, then prepared for some rocky economic data through 2018 because of the revenue and expense timing strategies that small and closely-held large business will employ.

The most important part of the corporate tax reform is the return to a territorial rather than global tax system. The global system is what caused the buildup of trillions of dollars in overseas subsidiaries of US companies that have not been repatriated. It created tax havens, such as Ireland, for corporate entities, especially new IPOs. Most every new major publicly traded company has one of these tax structures at its core. For new IPOs, this structure has been expected, and has been to their advantage; older, established corporations could not always take advantage of it, and some that did, put themselves up for sale to foreign acquirers.

Corporate tax rates have fallen worldwide and the US has become very uncompetitive. But it’s not just rates alone. A look at the upcoming 2018 Index of Economic Freedom rankings shows the US ranked as #48! In 2008, it was #5. There have been many anti-competitive policies that caused the rank to fall, but that’s not the main reason behind it all. It’s the fact that so many countries have aggressively reduced their corporate tax rates and the eased the aspects of starting and running businesses that have caused countries to climb in the rankings. The rankings, to be published in full in January, are reason for optimism for worldwide economic growth. US tax reform can be the engine for a worldwide recovery and regional booms. When the benefits of tax avoidance are greater than the returns from investing in production and the creation of goods and services, that creates counterproductive malinvestments. Consumers are deprived of innovation and better-priced goods. It appears that this problem is going to come to an end.

It would be better if the corporate federal tax rate was zero, with the taxation of profitable corporate operations being paid by the owners. Corporate taxes are in the prices charged to the consumers of the goods and services that the corporations create and offer for sale. Having a rate of zero would reduce the incentives for companies to borrow money, which creates an expense, and increase the incentive for paying dividends. Now, we have companies borrowing money to buy back their stock, a strange use for borrowing, created by the way corporate profits and dividends are taxed. State and local taxes are more logical for corporations to pay as their operations consume and affect the resources around them.

The repatriation of profits is one of the goals of tax reform. I remain skeptical about the magical windfall that is supposed to occur. Most of the funds are from profits in countries that have high growth rate from growing populations and rising incomes. The money may very well stay within those countries because of those demographic trends. Some of those funds have already been used as collateral for borrowing. The funds have already been at work inside those corporations; the resources have already been tapped.

Capital gains rates will stay about the same as they are. Unfortunately, there is no provision for inflation-adjustment for the sale of long-term assets. There is a horrid provision related to the sale of investments where you will no longer be able to specify which shares of stock you are selling but must sell shares based on FIFO. This will also create situations of sales of investments just as a basis of “wash sales.” A wash sale is the sale of an investment that decreased in value to balance off one that increased, just to avoid the capital gains tax. This is a distortion of investing, where portfolio reallocation is made because of tax consequences rather than the true organic value of the holding. Fortunately, individual retirement and other accounts are not subject to this rule. This affects small businesses, however, so it tends to be ignored by legislators and the press. Because they often use personal funds as a buffer against business disruption, tying up money in retirement accounts and other tax-favored investments is not practical. This will be a mess if retained; there are some cynics who say it was left in just so they could take it out in the reconciliation process and claim a victory. Interestingly, the mutual fund industry lobbied for an exemption, which they got.

One area of interest is the full expensing of capital purchases. This has been available to small businesses up to a limit, but this would be a big change by broadening it to all businesses. The biggest problem with depreciation schedules and amortization is the effect of inflation. If inflation is 2% a year, and you have a $100 asset with a cost that is spread evenly over ten years, that tenth year’s depreciation is lower in real value by 20%. I’ve never been a believer in the magical effects of immediate expensing because most of big purchases are financed, and all of the long term calculations of capital investment include net present value calculations, and include inflation factors. This is strictly a tax calculation; just because it makes taxes better does not mean it’s a wise value creation investment.

Neither tax reform plan has full expensing but it shortens depreciation schedules to five years for most items and shortens the depreciation time for buildings and similar assets. Details are sketchy; this is better than it was, and it may not be until the IRS regulations are written. The legislation is likely to only have broad guidelines with little specifics. (Did someone say “we have to pass it to find out what’s in it?”)

The reform of taxes for individuals is good, too, with a bigger standard deduction that will allow more taxpayers to avoid itemizing deductions and save of tax preparation costs. The standard deduction is almost doubled to $12,000 for a single taxpayer and $24,000 for a joint return. This can drastically change the nature of tax decisions of many households, especially those without wages, such as retirees. Estate tax limits are raised significantly, which means that many families will no longer have to be concerned about it, reducing the need for trusts or insurance products to deal with the tax. There are many issues that need to be ironed out, especially for those taxpayers in states with notoriously high property tax rates. There is a limit, in both bills, of $10,000 the property tax deduction. Big party donors live in these geographies, meaning it will be raised or eliminated.

Happy Recession Anniversary

It’s ten years since the recession began in December 2007, but it feels like nine, because the experts didn’t declare that it had started until eleven months later. That was the longest time lag between the onset of a recession to its declaration. There have been recessions that didn’t last that long! This wasn’t any recession, no, this was declared the Great Recession. The only time I had ever heard that “recession” word uttered so often prior to that was during visits to my dental hygienist.

The end of a recession is its lowest point, and that is the date that the recovery begins. July 2009 is that time.

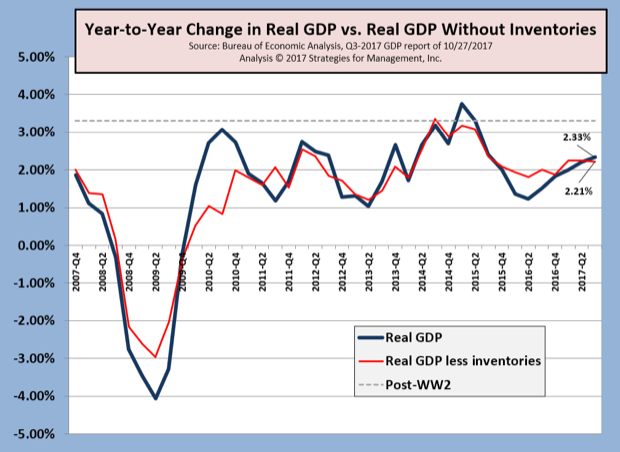

Here is the chart of the last decade with the latest revision of GDP data. The data are on a year-to-year basis. The dotted line is the post-WW2 average real GDP.

The latest real GDP estimate of Q3-2017 was raised to 3.3%. It was only the sixth time that quarter-to-quarter GDP has hit the post-WW2 average since the July 2009 recovery. The higher inventories in the revision kept the year-to-year inventory growth rate at 2.21%, so there was no change to our chart.

The Atlanta Fed’s GDPNow estimate for Q4 is at 3.5%. If that remains at that level, real GDP for the year will be about 2.8%. That would be the highest annual rate since 2005, which was 3.3%.

Most measures of the post-recession economy have not fared as well as real GDP, with many of them still not recovered. It is likely that tax reform, even the flawed version that is near passage, will finally push the economy up past those levels of stagnation. The possibility of a boom 18 months from now is rising. But… we don’t have a law until it passes.