By Michael Josefowicz January 16, 2006 -- First comes the technology, then come lots of "wild-eyed" predictions of the revolution to come. While some of the predications may be correct, the time frames are often way off. The supporting ecosystem takes a while to develop. But eventually it does. Then real people start changing their day to day behavior. And the culture starts changing. The tech gets faster, better and cheaper. Price points fall, access increases, and more people change their behavior. And then, new business models are invented and entire industries are reinvented--seemingly overnight. A developed digital print network poses a dangerous situation for the textbook industry, which is based on controlling access to content. With the emerging ubiquitous digital print platforms, textbooks and professional books may be the next to go. Printers and publishers can hide their heads in the sand, or they can keep a watchful eye on this development, and prepare for the change. Textbooks and professional books - anytime, anyplace, in any format A couple of years ago there was a lot of ballyhoo about e-books. The internet evangelists believed that books would disappear. But the book people were right. The technologists seriously underestimated the usefulness of books. It turns out that printed output has its own unique advantages that are not going away any time soon. But now, ten years later, with a developed digital print network, the ecosystem has changed again. SONY has unveiled a new generation of e book readers based on e paper technology with a $200 price point. Education and professional consumers can now choose whether they want their books in digital form or in printed output form. They can get what they want, when they want it, and how they want it. It has become a dangerous situation for the textbook industry, which is based on controlling access to content. The last hurdle are the price points. $75 textbooks offered in electronic versions for $30 is not going to do it. The secret sauce was showing the music industry how it could make money from disruptive innovation. It would be nice from the publishers point of view, but I don't think it's going to fly. $10 might or maybe a site license structure will. Maybe it's a subscription model a la netflicks.com, or the 99-cent download model of iTunes, or Google's ad-supported model. Or perhaps textbooks will be bundled with a hardware or software purchase like Encarta. There are many possibilities, but there is little question a new model will emerge. Steve Jobs, as he has in other areas, led the way for music. The iPod is not a technological marvel. It's just a very well designed portable hard drive elegantly connected to the Internet. The secret sauce was the business model that showed the music industry, in spite of it's own furious resistance, how it could make money from disruptive innovation. Apple imagined a new way of doing business, so that non-consumers could be brought into the market and the music publishers could continue to make money. It's the kind of win-- win that leads to sustainable innovation and explosive growth. Now that the stampede has begun, the game begins in earnest. The new model is becoming the common wisdom. With the common wisdom comes big budgets. With big budgets come tipping points-- and the opportunity to make healthy profits. By solving it first in the music world, Apple became the de facto leader. Once a stampede begins, it's much better to be in front of it then someplace in the middle. What might this mean for the textbook business? According the Association of American Publishers, the publishing market in 2004 was $23 billion, of which textbooks for K-12 and College were $7.8 billion. Professional books contributed another $4 billion. Just for perspective, the whole trade book business is only $5 billion. The text book market has historically not been consumer-driven. Students do not make the purchase decision in higher ed. The classroom teacher does not make the decision in K-12. Instead, it's a third-party-payer system, where a school board or a professor decrees that a purchase must be made, and the student, the student's parents or the public winds up paying for it. Usually in these kinds of situations, the cost of sales can be high, but the profit margins are relatively comfortable. The Internet seriously undermines the value propositions that have supported the textbook value chain The Internet seriously undermines the value propositions that have supported the textbook value chain; control of the sales process, the ability to print and deliver huge quantities of books, and the control of content creation. Getting a critical mass of school boards to approve a textbook is a very expensive, difficult process. Printing, storing and delivering textbooks requires large integrated manufacturers. Producing acceptable content has been time consuming and expensive. But, as the music industry has learned, control of 20th century delivery channels for information content is not a defensible advantage. Standards-based education is making content creation much more definable. Access to content producers is no longer only, or even best done, in a large established corporate environment (consider Linux and the entire open-source software movement). And on-demand printing changes the paradigm of "print a lot, store a lot and distribute often" to a paradigm of distributing digital files and printing what you need and shipping directly to the end-user, eliminating storage completely. Textbooks are very expensive, consume lots of resources, get out of date pretty quickly and at the end of day, don't really work very well. This shouldn't really be a surprise, given how far away the editorial and purchasing decisions are from the end user and how many constituencies have to approve the content. Coming tomorrow: A Broken Product Ripe for Disruptive Innovation. Michael Josefowicz expands on his thinking--and how companies can take advantage of the opportunity. The question is, does anyone have the courage to foment change? And who will it be?

Commentary & Analysis

iPods and Textbooks

By Michael Josefowicz January 16,

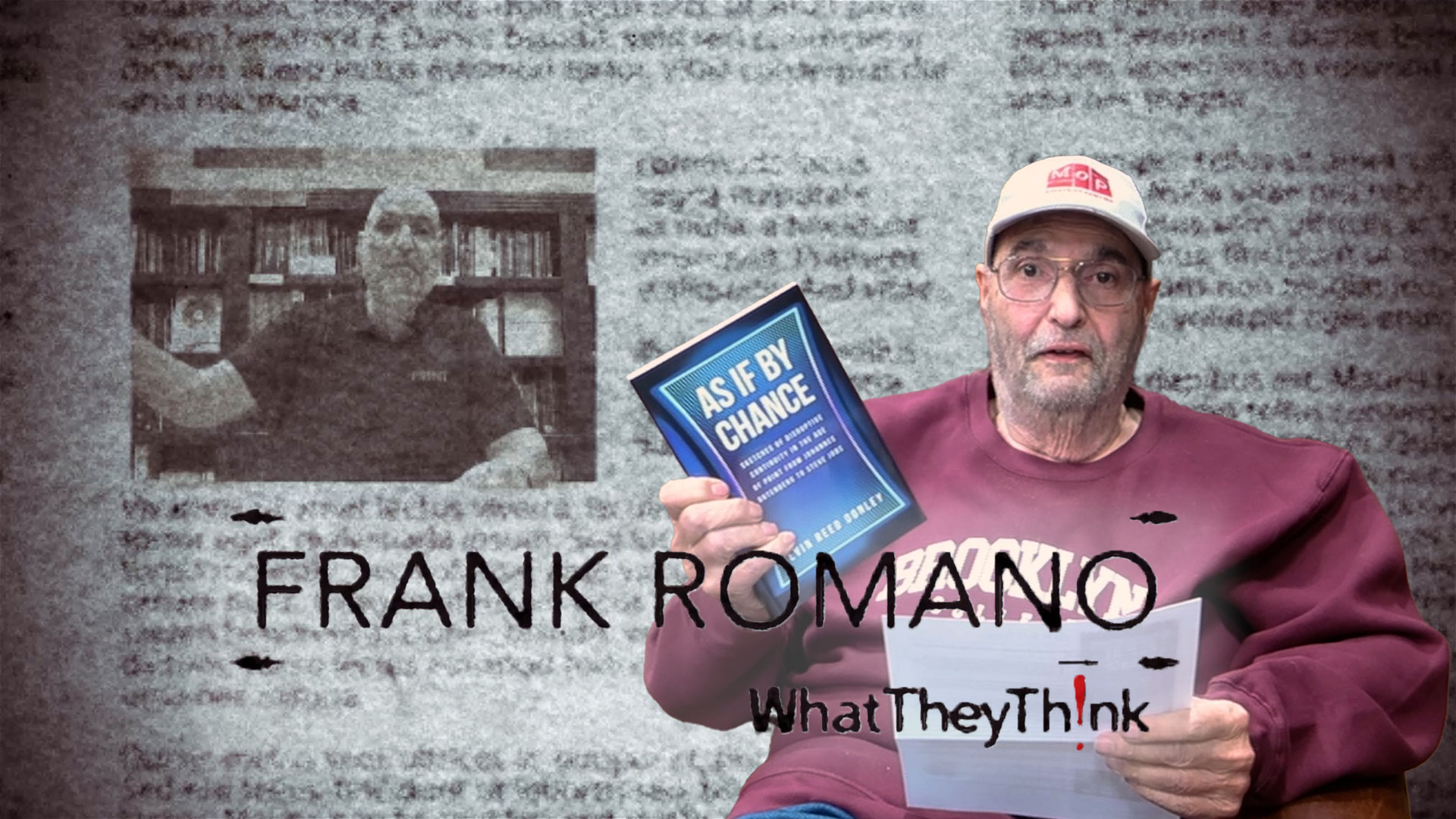

About WhatTheyThink

WhatTheyThink is the global printing industry's go-to information source with both print and digital offerings, including WhatTheyThink.com, WhatTheyThink Email Newsletters, and the WhatTheyThink magazine. Our mission is to inform, educate, and inspire the industry. We provide cogent news and analysis about trends, technologies, operations, and events in all the markets that comprise today's printing and sign industries including commercial, in-plant, mailing, finishing, sign, display, textile, industrial, finishing, labels, packaging, marketing technology, software and workflow.

WhatTheyThink is the official show daily media partner of drupa 2024. More info about drupa programs

© 2024 WhatTheyThink. All Rights Reserved.