By Kelly Lawrence

(This article originally appeared on Inkjet Insight.)

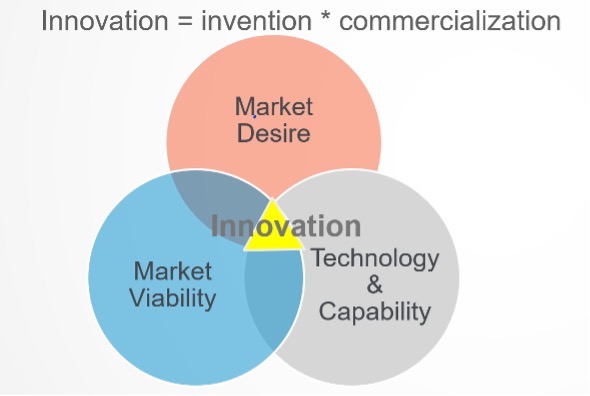

Innovation is the intersection of unmet customer needs, an internal capability to solve the problem better than anyone else, and economic viability. In other words, there must be a problem to solve, your organization needs to be able to solve the problem, and the numbers have to work for your organization and your customer.

To be a true innovation, the solution must be commercialized and it must generate profit. This can be looked at as three key components:

- (Commercialized) Technology or capability

- Market Desire

- Market (Commercial) Viability

Miss one of these critical pieces and you are likely to struggle with innovation.

Technology & Capability

Technology sitting on a shelf that hasn’t been commercialized is a technical capability waiting for the right problem to solve. That technology might be patented. Many organizations use the number of patents as an innovation metric.

There are a number of inkjet players that regularly publish and win new patents. Examples include industry giants such as HP, Epson, Canon, Kodak, Fujifilm, Konica Minolta, and many others. These patents can be a great thing or they can be a huge waste of money and resources depending on the situation. Has the technology generated any new products? Are those products commercialized? Are those products generating revenue and acceptable profitability? If the answer is no, the technology is not an innovation yet. The organization has to decide if it’s worth the cost to maintain patents in the event the technology cannot be leveraged to solve a profitable problem. Trade secrets of course also may also have a place in a company’s strategy.

Think about a print show you attended: drupa, PRINTING United, FESPA, LabelExpo. Now think of all the cool things you saw there. Did they all successfully launch? Did they all bring in the revenue the inventing company promised? As one example, I recall a lot of hype around new pigment inks designed for the direct-to-garment market that intended to enable printing on dark colors of polyester T-shirts. Yet, DuPont remains a key ink supplier and the market has since seen the growth of a different inkjet technology, direct-to-fabric printing.

Even if your organization has the technology, can that technology be scaled and commercialized? I’ve seen new products that worked great in a lab die because they could not be successfully scaled. You’ll want to ensure scalability to an acceptable level when assessing if a technology is likely to make it into a viable product. Ensure the product does what you say it will when made at scale.

Market Desire

Having a problem that is a big enough annoyance that it needs to be solved is the root of an innovation. For many inkjet markets, concerns over nozzle clogging led to the development of recirculating ink systems. For inkjet textile, there was a desire to print pigment due to lightfastness properties and a simplified process that eliminated a need for steaming and washing commonly needed when printing with dye inks. In the earlier days of wide-format inkjet textile printing, Kyocera had the dominant head technology, but the small nozzles made pigment inkjet development challenging. This unmet need drove head developments from a number of players, Fuji Film, Konica Minolta, and Epson to name a few.

Inkjet label printing saw innovation driven by regulatory changes in end use markets. These regulatory changes forced chemical manufacturers to change the labeling of chemicals being sold overseas. It drove a demand for variable color print labels. A number of manufacturers including UPM Raflatac, Avery Dennison, and FLEXcon introduced inkjet label stock that addressed that variable print needs while being able to pass the new BS5609 regulatory standard.

In each of these market scenarios, a need drove the decision. If you don’t have a need, you don’t buy. Let’s say I run a print shop. I do a few million impressions per year and have excess capacity. My customers are loyal. They come to me with repeat business as well as their most challenging print jobs. An OEM comes to me and offers to sell me a faster printing press. I don’t need it. Why? I’m already satisfied with my existing press. I have extra capacity so I don’t need press speed that would further expand my extra capacity.

In fact, my rate limiting step is my finishing process. If my press is faster than finishing, I’ve got a bottleneck going on in my operations. A faster press won’t fix my problem—it just adds to the bottleneck. I’m not a good target for the OEM with the faster press. However, I may have a challenge winning new customer business for unique printing jobs.

If that same OEM took time to ask me about my challenges, I might bring these up. The OEM might learn that I having a growing need to provide tamper evident packaging and security labels. If the OEM understands my needs, the OEM is more likely to sell me equipment that solves that need. When you design innovation for inkjet, consider how your product benefits a potential customer. If the customer is satisfied, you don’t have the business case for an innovation. Find a new problem to solve.

Market Viability

Just because an organization can make a product does not mean that it can do so in an economically viable way. For every product, there is a price ceiling. This is the maximum amount a customer will pay for the given product. If your product is priced above the price ceiling, it won’t sell. Customers do not care how much it costs your organization to make a product. Customers only care about the cost to them for a given value. If the cost and value do not align. Do not expect to sell.

Your Innovation Portfolio

Under a definition of innovation that requires technology and capability, market desire and market viability, what percentage of your new products and services are truly innovations? If the percentage is low, you have a lot of company. Most companies struggle to build a portfolio of true innovations. The good news is that the portfolio and the skills of the team can be improved. Doing so will accelerate innovation success and drive results.

Kelly Lawrence is a recognized business growth expert and the Founder and CEO of Lawrence Innovation, LLC, a business growth advisory. Kelly’s clients learn the process, insights, strategy and tactics to deliver new business results through innovation. Kelly helps clients win in new markets, develop and launch new technologies, products and services and establish new business models that generate sustainable profitability. Kelly has served the print industry for over 20 years – first as print specifier with Fortune Brands' Moen, and later as a print innovator with Berkshire Hathaway's Lubrizol. Lawrence now serves the print industry as a contributor to Inkjet Insight and an Associate Consultant with Smithers. Connect with Kelly on LinkedIn.

Discussion

Only verified members can comment.