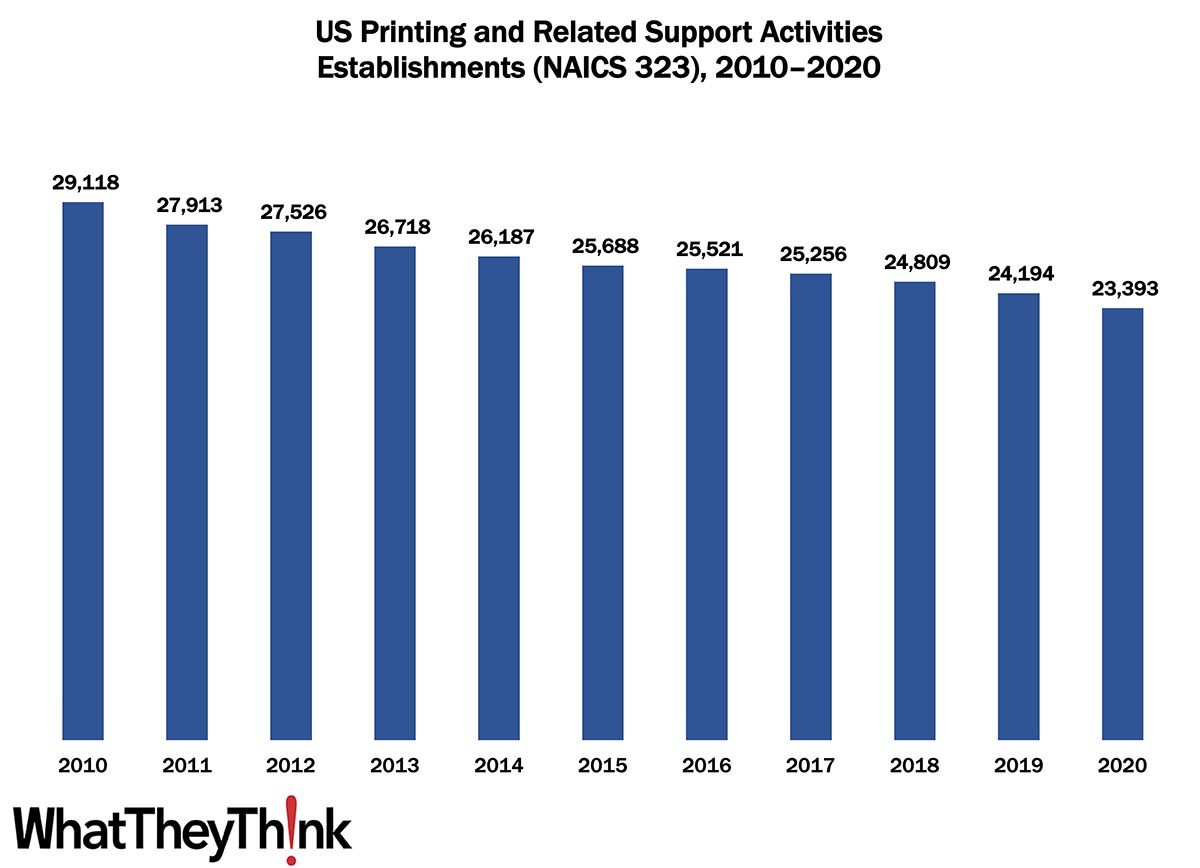

The latest edition of County Business Patterns was just released, which includes 2020 data. If you’re like us, a frisson of terror shot down your spine at seeing that year, but actually CBP 2020 data reflects the number of establishments as of Q1—so these counts are pre-COVID. We’ll have to wait until 2021 County Business Patterns to see the impact of the pandemic on the number of printing establishments. Still, it wouldn’t hurt to start drinking now.

As 2020 began, there were 23,393 establishments in NAICS 323 (Printing and Related Support Activities). This represents a decline of 20% since 2010. The biggest declines were in the early years of the decade, thanks to the Great Recession—from 2010 to 2011, establishments declined by 4%; from 2014 to 2015, the decline was only 2%; and from 2016 to 2017, the decline was 1%. Consolidation picked up toward the end of the decade, with establishments declining 6% from 2018 to 2020.

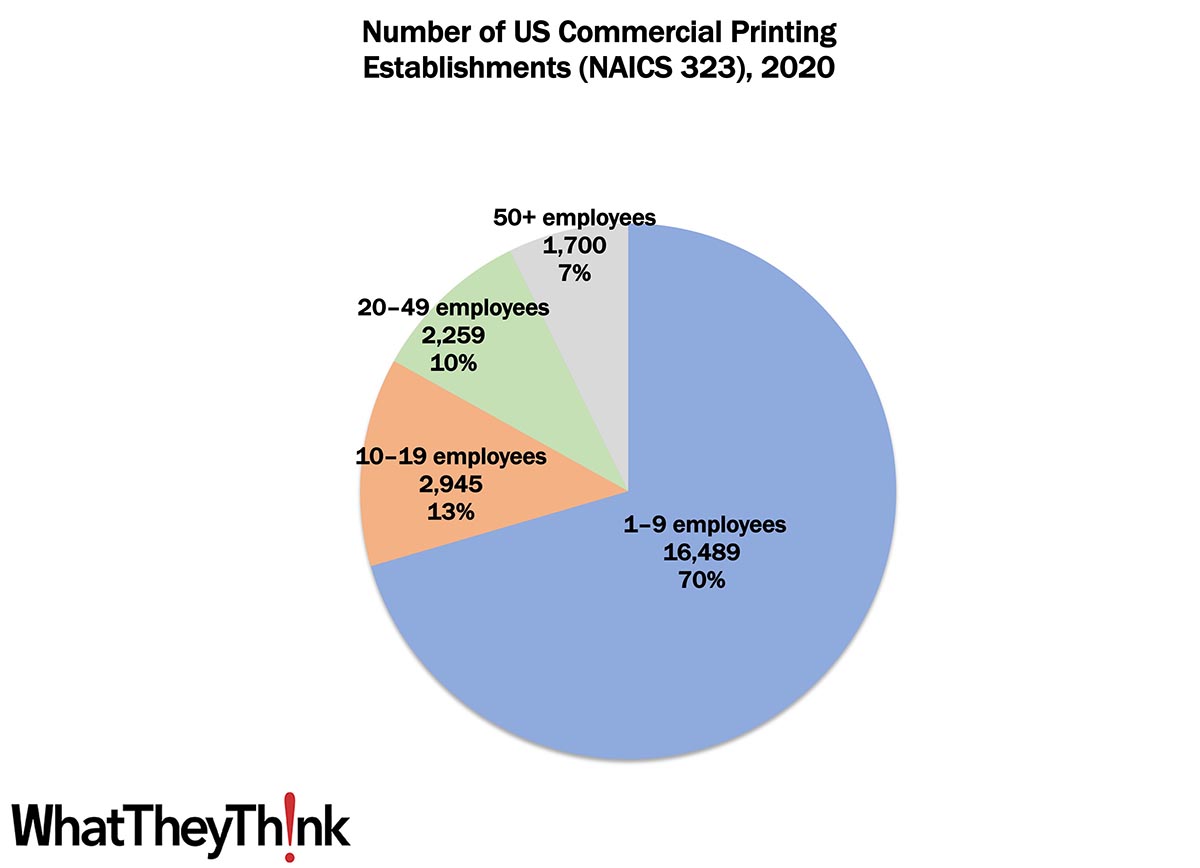

Small shops (1 to 9 employees) still comprise the bulk of the industry, accounting for 70% of all establishments. The largest shops account for only 7% of industry establishments with mid-size shops accounting for about one-fourth of establishments. These percentages have not varied substantially since at least as far back as 2010.

These counts are based on data from the Census Bureau’s County Business Patterns. Throughout this year, we will be updating these data series with the latest CBP figures. County Business Patterns includes other data, such as number of employees, payroll, etc. These counts are broken down by commercial printing business classification (based on NAICS, the North American Industrial Classification System):

- 323 (Printing and Related Support Activities)

- 32311 (Printing)

- 323111 (Commercial Printing, except Screen and Books)

- 323113 (Commercial Screen Printing)

- 323117 (Books Printing)

- 32312 (Support Activities for Printing—aka prepress and postpress services)

These data, and the overarching year-to-year trends, like other demographic data, can be used not only for business planning and forecasting, but also sales and marketing resource allocation.

This Macro Moment…

Estimates for Q2 2022 GDP are not rosy. Via Calculated Risk, Bank of America is predicting -1.2% growth for 2Q, the Atlanta Fed GDPNow is also expecting -1.2%, and Goldman is downright bullish at +0.7%. The mainstream media keeps stoking recession fears, but there is little evidence that we are in one or even approaching one. As BofA says:

It is reasonable to dismiss some of the signal from the GDP declines that may have taken place in the first two quarters of the year on account of the large negative contributions from net trade and inventories. In addition, there is a larger-than-normal gap between GDP and GDI which, historically, has been resolved by GDP getting revised toward GDI, suggesting that some of the as-reported weakness in activity may get revised away over time.

GDI is “Gross Domestic Income,” and while GDP is the value of all the goods and services produced in the US, GDI is the sum of all the income needed to produce those goods and services. Theoretically, the two figures should be the same, but given the difficulty in measuring either of them precisely, there is always some statistical discrepancy, although at >3%, the current GDP/GDI discrepancy is a couple of percentage points higher than normal. Essentially, GDP shows the economy is shrinking, while GDI shows that it is growing. Which is it? James Bullard, president of the St. Louis Fed, feels that GDI at the moment is more in line with other economic indicators.

“At this point, it appears that the GDI measure is more consistent with observed labor markets, suggesting the economy continues to grow,” Bullard said in remarks accompanying the slides, noting that labor markets are “robust” and by a broad swathe of measures stronger than they have been in more than 20 years.

Ultimately, the big issue in the economy right now is inflation, and while it’s nothing to sneeze at (especially if there are still tissue shortages) it’s more of a supply issue than anything, and if the Fed gets too heavy handed, there is the very real chance they’ll cause a recession. After all, it’s happened before.