A Thai businessman owns Fortune Magazine.

A Thai businessman owns Fortune Magazine.

A dot-com billionaire owns Time Magazine.

The widow of Apple’s founder owns The Atlantic Magazine.

A retail disruptor (and wealthiest person on earth) owns The Washington Post.

Never heard of Chatchaval Jiaravanon, the Thai businessman whose family controls Charoen Phokkhaphan, the largest conglomerate based in Thailand which employs over 300,000 people in over 30 countries? Neither had I until learning that he stepped up and paid $150 million for the iconic chronicle of American industry and business, Fortune Magazine. The Thai billionaire apparently jumped into the bidding when Marc Benioff, founder of software company Salesforce, switched gears and decided to buy Time Magazine instead of Fortune.

Fortune Magazine has been my window into the world of big business since I first subscribed in 1980. I’ve read every issue since, cover-to-cover. The articles in Fortune have been extraordinarily insightful and topical, the research, writing and graphic design top-notch. Even though Fortune is not focused on the smaller privately-held companies that I have owned and/or worked for, the larger companies featured in the pages of Fortune were my customers and those companies set the macro-economic trends that influenced my business life.

Over the past couple of years, as advertisers have moved their advertising budgets from the printed page to digital channels, Fortune magazine has gotten thinner, the paper lighter, and the deep journalistic dives fewer. Recent issues have featured more “sponsored” content, code for advertising disguised as an editorial piece, replete with copy that drones on about the wonders of doing business in Dubai or some other inane topic. If my subscription was not on auto-renew, I suspect that my decades-long habit of readingFortuneon my lunch break would have ended with nary a blip in my routine.

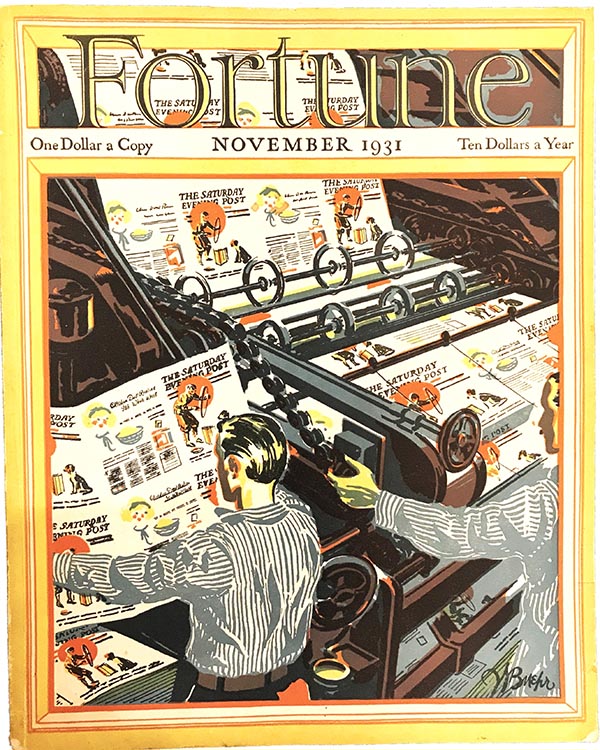

My collection of antique Fortune magazines offers an amazing journey into history; history written as it occurred. In one of the very early issues, November of 1931, the topics covered included: government intervention in farm productivity, the politics behind the growing Port of New Orleans, an accounting of war reparations from World War I, the new unemployment relief programs, the Cleveland orchestra (with color illustrations of each instrument), Soviet propaganda posters, deep sea salvage, outfitting the babies of the wealthy (after all, the magazine was named Fortune), the rising economy of Brazil, and a photo essay of Europe’s top statesmen caught in casual poses (including Mussolini scowling at his guests over coffee).

If it’s possible, the advertising might even be more interesting than the editorial: furs, furniture, clothing, top hats, horse-riding kits, cruise lines, exotic travel destinations (Miami and Hawaii were exotic at that time), yachts, and fine art. These products were among the ads in the November ’31 issue, all aimed at the top earners in society. Other ads were more industrial: plugging the makers of aluminum, brass, bolts, pipes, ball bearings, cars, trucks, and cement. Banks and insurance companies were vying for attention. The back cover, clearly the most expensive advertisement in the book, featured a handsome football player and two very fashionable adoring young ladies enjoying their Camel cigarettes under the headline “something worth cheering about.”

Of special note to those of us in the printing industry, paper manufacturers such as Crane’s Bond, Gilbert Paper and Kimberly-Clark advertised often in the early issues of Fortune to reach the top echelon of American business. Fine writing paper was touted as a necessity promoting the image of a successful company. The cover of November ’31, one of my favorites, was not an illustration of a ship, a plane, a train, or a steel furnace, but rather the image portrayed was that other important driver of economic growth, the printing press, turning out an issue of The Saturday Evening Post.

Without exception, the billionaires, the new owners of these iconic American titles, have vowed to stay out of the editorial side of the enterprise. Their statements are refreshing, especially after all the thrashing about at Time, Inc. over the past several years that management was breaking down the walls between the editorial and business departments, eliminating the firewall between “church and state” that has sustained an editorially independent press. We need a new model of support for the free press, and what appears to be emerging is ownership of these publications by people who are so wealthy that they can sit by and sustain the losses incurred by these broad-based general interest publications. The notion of a billionaire-supported free press is suspect, at least in my opinion, since the century-old advertiser-supported model relied on a constantly evolving and very diverse foundation of revenue sources, none alone so powerful that they could suppress the robust independent journalism we have enjoyed for so long. The new mogul-supported model concentrates the financial support in the hands of a very select few, however well-meaning their initial intentions.

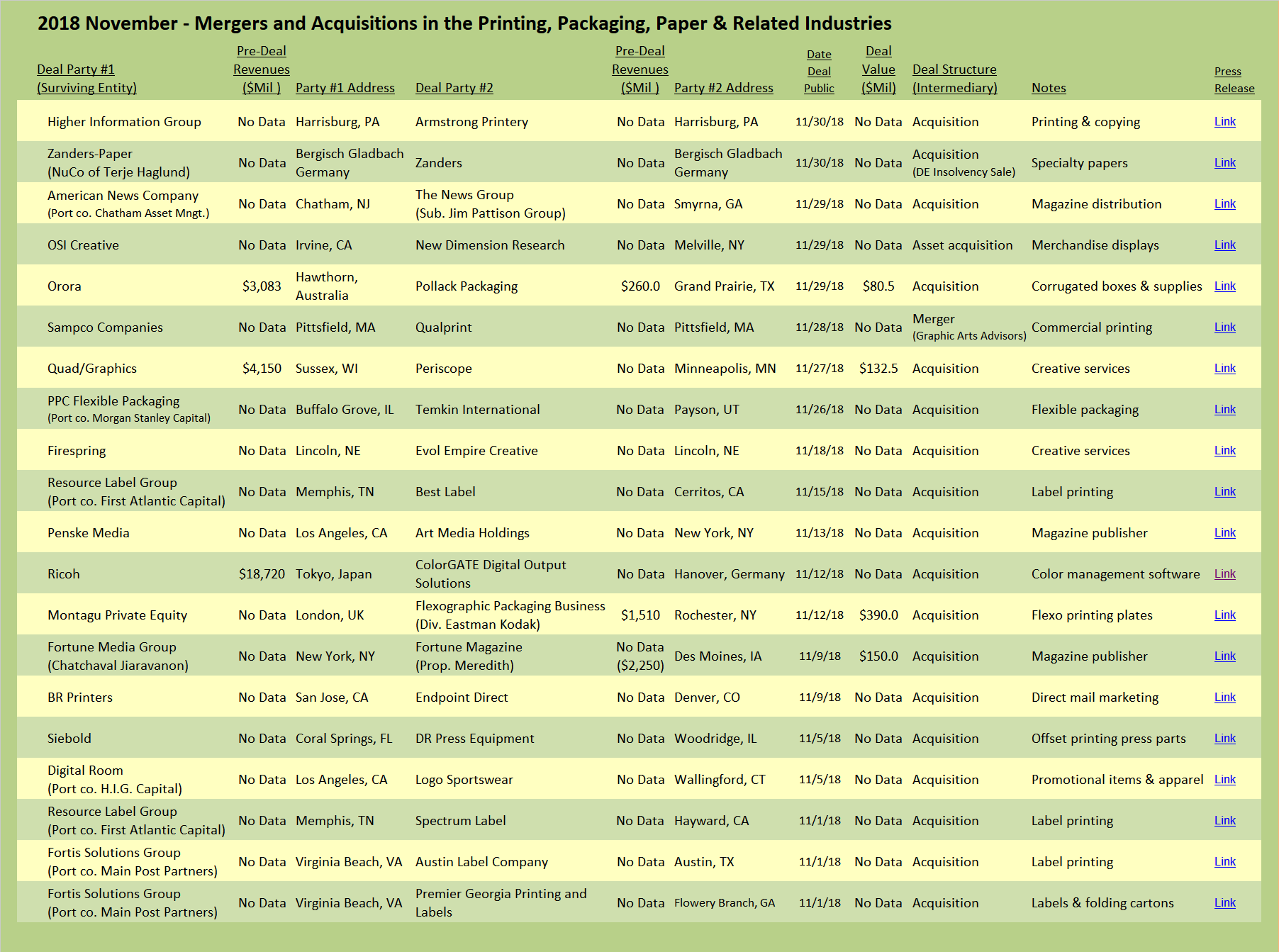

Printing and Creative Services

After its print-affirming acquisition of LSC communications, announced last month, Quad/Graphics got back on course with its “Quad 3.0” strategy, announcing the acquisition of Periscope. The acquired company appears to have all the hallmarks of an upscale, hipster, chic, creative agency in a sophisticated urban setting, complete with rooftop garden meeting area and open work spaces (lest you doubt my “hipster-chic” characterization: no less than six dogs are featured prancing around the office in the one-minute intro video on the website). The Periscope deal mirrors Quad’s September acquisition of Peppermint Warszawa, an upscale creative agency in Warsaw, Poland.

Quad took baby steps into creative digital services back in 2014 when it acquired Brown Printing as part of its “Quad 2.0” strategy of consolidating the large printer segment of the industry. In that transaction, Quad landed the digital and mobile agency Nellymoser, which Brown had previously acquired (see The Target Report: Is the Printing Industry Devolving or Evolving? – March 2013), eventually rolling Nellymoser into its homegrown BlueSoHo creative production boutique.

A much bigger step, really more of a leap, was accomplished earlier this year when Quad acquired Ivie & Associates, the Texas-based marketing production services and marketing execution company (see The Target Report: Turning a Big Ship – Quad/Graphics Acquires – February 2018). Also in line with the “Quad 3.0” strategy was the acquisition of digital marketing services company, Rise Interactive, announced in March of 2018.

Joel Quadracci, chairman of Quad/Graphics, in the press release announcing the Periscope deal, proclaimed that the acquisition will create an “integrated end-to-end marketing platform that we believe will create more value than the traditional siloed agency approach.” Of course, the big advertising agencies (and let’s not exclude the global print management companies) are not waiting around quietly while Quad conquers the higher ground on the creative process ladder. I can hear the retort coming—what could be more siloed than a large capital-intensive, heavy-machinery, industrial printing company trying to integrate with a human-intensive, young, hip, group of creatives that bring their dogs to work and walk out the door at the end of every day?

While I wouldn’t bet against Quad succeeding in carving out a space somewhere in between the top creative agencies and hard-core industrial-strength printing, it’s clear that Quad is covering its bet on the “3.0” creative strategy with the game-changing and much larger pending acquisition of LSC Communications. When that transaction is complete, Quad will instantly vault to the number one position and become the biggest printing and publication logistics company in the US.

On a much smaller scale than Quad, Firespring, headquartered in Lincoln, Neb., continued its evolution into a one-stop marketing services provider with the acquisition of Evol Empire Creative. Evol, as the acquired company is known, specializes in interactive digital, website design and video production. Firespring has grown through a series of acquisitions, including the August 2016 purchase of Jacob North Media Solutions which brought significant print capacity and expertise to the group. That same month, the company acquired an online crowdfunding platform, Deposit a Gift, bringing a unique fundraising service to its focus on the non-profit sector. Firespring has its roots in printing, originating in 2015 as a mash-up of five small printing companies. Mailing services were added shortly after the initial formation of the company with the purchase of On-Time Marketing. Firespring now has more than 200 employees and appears to be delivering on the concept of what a marketing service provider can become, a creative force in its market while still maintaining a strong core print component.

Labels

Private equity interest and activity in the label printing segment remains very strong. Fortis Solutions Group, a portfolio company of Main Post Partners, announced a double header deal with the acquisition of Premier Georgia Printing and Labels located in Flowery Branch, Georgia and the Austin Label Company located in Austin, Texas. The Georgia company also produces folding cartons.

Resource Label Group, with the backing of First Atlantic Capital, acquired Spectrum Label in Hayward, California. The acquired company produces pressure sensitive labeling. Two weeks later, Resource Label Group acquired Best Label, located in Cerritos, California. Best Label also produces pressure sensitive labeling, using letterpress, flexo and digital printing processes. (For more, see The Target Report: Private Equity LOVES Labels – August 2016).

View The Target Report online, complete with deal logs for November 2018