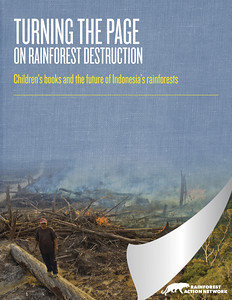

ainforest Action Network’s recent analysis of the paper used in children’s books published by the top-ten U.S. children’s book publishers revealed that 90% of these publishers had published at least one in three books on paper containing tropical wood fibers linked to the clearing and conversion of Indonesia’s rainforests.

This is disturbing on a number of levels. The first is that of printing jobs being sent offshore. The books sampled for the RAN study, all “U.S. titles,” were printed in China. That should come as no surprise, as North American publishers increasingly have been outsourcing their printing to China for some time.

According to Joe Webb’s 2005 study, costs is the driving factor here, as Chinese printers can produce projects at as much as 30-50 percent savings over domestic sources. Lower labor costs, newer equipment, and, at times, subsidized paper costs contribute to these savings. According to the United Nations Commodity Trading Database, Chinese sales of children’s picture books to the U.S. grew by more than 180 percent during the period 2000-2005, with an average increase of more than 35 percent per year. Today, 50 percent of the children’s picture books printed on coated paper and sold in the U.S. are printed in China.

A second area of concern is the voracious appetite of the Chinese printing and paper industry for market pulp, and the effects of that pulp production on exporting countries. Though China does have its own pulp industry, the volumes of paper demanded by printing in China will outstrip internal pulp-making capacity for at least a decade, according to a 2005 CIFOR report by Barr and Demawan on China’s plantation-based wood-pulp industry. At present, China’s top six pulp supplying countries are Canada (20% of total imports), Indonesia (18%), Brazil (14%), Russia (14%), the U.S. (11%), and Chile (10%).

Some of these countries adhere to rigorous national forest management standards, and others simply do not. Some, such as Chile, have a well-established, size-stable base of sustainable plantation forests, and have in place well-document commitments not to harvest native forests In other countries, such as Indonesia, the demand for increasing quantities of pulp is driving continued conversion of natural forests to plantations. This conversion continues despite temporary regional moratoriums and national “cease-conversion” deadlines that never seem to be set in stone. (The report brochure contains a discussion, from RAN’s perspective, of the many issues surrounding forestry in Indonesia. The document is available in PDF format here (1.3Mb).

But just how did RAN identify the Indonesian fiber content in these children’s picture books? It relied on the same sort of fiber analysis performed for U.S. paper manufacturers when investigating a customer’s paper claim. And it used one of the very same facilities the industry uses, the Integrated Paper Services (IPS) laboratory in Appleton, Wisconsin.

RAN randomly selected three children’s books from each of the ten top U.S. children’s book publishers. All of the books were printed in color, and all were printed on coated paper and manufactured in China. Between November 2009 and April 2010, the 30 books were analyzed to determine if they contained tropical wood content, including species that occur in natural tropical forests (known in the trade as “mixed tropical hardwoods” or MTH) and plantation-grown acacia.

Eighteen of the 30 books tested positive for significant percentages of tropical wood content. In each of these 18 positive samples, acacia fiber was present. In four of the 18 positive samples, MTH fiber also was found.

According to Lafcadio Cortesi, Forest Campaign Director for RAN, the research did not include DNA testing that might have been used to determine the specific clone of acacia used to make the paper. And, because the study pre-dated the phase in of Lacey Act documentation provisions, a comparison of fiber found with stated fiber content could not be performed.

RAN has not yet announced any plans for public days of action based on the findings of the report, but it is likely that the ENGO will to focus some behind-the-scenes efforts to convince major U.S. publishers to use their purchasing power to influence the paper-procurement decisions of domestic and offshore printers alike.

ainforest Action Network’s recent analysis of the paper used in children’s books published by the top-ten U.S. children’s book publishers revealed that 90% of these publishers had published at least one in three books on paper containing tropical wood fibers linked to the clearing and conversion of Indonesia’s rainforests.

This is disturbing on a number of levels. The first is that of printing jobs being sent offshore. The books sampled for the RAN study, all “U.S. titles,” were printed in China. That should come as no surprise, as North American publishers increasingly have been outsourcing their printing to China for some time.

According to Joe Webb’s 2005 study, costs is the driving factor here, as Chinese printers can produce projects at as much as 30-50 percent savings over domestic sources. Lower labor costs, newer equipment, and, at times, subsidized paper costs contribute to these savings. According to the United Nations Commodity Trading Database, Chinese sales of children’s picture books to the U.S. grew by more than 180 percent during the period 2000-2005, with an average increase of more than 35 percent per year. Today, 50 percent of the children’s picture books printed on coated paper and sold in the U.S. are printed in China.

A second area of concern is the voracious appetite of the Chinese printing and paper industry for market pulp, and the effects of that pulp production on exporting countries. Though China does have its own pulp industry, the volumes of paper demanded by printing in China will outstrip internal pulp-making capacity for at least a decade, according to a 2005 CIFOR report by Barr and Demawan on China’s plantation-based wood-pulp industry. At present, China’s top six pulp supplying countries are Canada (20% of total imports), Indonesia (18%), Brazil (14%), Russia (14%), the U.S. (11%), and Chile (10%).

Some of these countries adhere to rigorous national forest management standards, and others simply do not. Some, such as Chile, have a well-established, size-stable base of sustainable plantation forests, and have in place well-document commitments not to harvest native forests In other countries, such as Indonesia, the demand for increasing quantities of pulp is driving continued conversion of natural forests to plantations. This conversion continues despite temporary regional moratoriums and national “cease-conversion” deadlines that never seem to be set in stone. (The report brochure contains a discussion, from RAN’s perspective, of the many issues surrounding forestry in Indonesia. The document is available in PDF format here (1.3Mb).

But just how did RAN identify the Indonesian fiber content in these children’s picture books? It relied on the same sort of fiber analysis performed for U.S. paper manufacturers when investigating a customer’s paper claim. And it used one of the very same facilities the industry uses, the Integrated Paper Services (IPS) laboratory in Appleton, Wisconsin.

RAN randomly selected three children’s books from each of the ten top U.S. children’s book publishers. All of the books were printed in color, and all were printed on coated paper and manufactured in China. Between November 2009 and April 2010, the 30 books were analyzed to determine if they contained tropical wood content, including species that occur in natural tropical forests (known in the trade as “mixed tropical hardwoods” or MTH) and plantation-grown acacia.

Eighteen of the 30 books tested positive for significant percentages of tropical wood content. In each of these 18 positive samples, acacia fiber was present. In four of the 18 positive samples, MTH fiber also was found.

According to Lafcadio Cortesi, Forest Campaign Director for RAN, the research did not include DNA testing that might have been used to determine the specific clone of acacia used to make the paper. And, because the study pre-dated the phase in of Lacey Act documentation provisions, a comparison of fiber found with stated fiber content could not be performed.

RAN has not yet announced any plans for public days of action based on the findings of the report, but it is likely that the ENGO will to focus some behind-the-scenes efforts to convince major U.S. publishers to use their purchasing power to influence the paper-procurement decisions of domestic and offshore printers alike.

Commentary & Analysis

Children's Books Linked to Rainforest Destruction? How Do They Know?

Rainforest Action Network’s recent analysis of the paper used in children’s books published by the top-ten U.S. children’s book publishers revealed that 90% of these publishers had published at least one in three books on paper containing tropical wood fibers linked to the clearing and conversion of Indonesia’s rainforests. But how do they know? And why should you care?

R ainforest Action Network’s recent analysis of the paper used in children’s books published by the top-ten U.S. children’s book publishers revealed that 90% of these publishers had published at least one in three books on paper containing tropical wood fibers linked to the clearing and conversion of Indonesia’s rainforests.

This is disturbing on a number of levels. The first is that of printing jobs being sent offshore. The books sampled for the RAN study, all “U.S. titles,” were printed in China. That should come as no surprise, as North American publishers increasingly have been outsourcing their printing to China for some time.

According to Joe Webb’s 2005 study, costs is the driving factor here, as Chinese printers can produce projects at as much as 30-50 percent savings over domestic sources. Lower labor costs, newer equipment, and, at times, subsidized paper costs contribute to these savings. According to the United Nations Commodity Trading Database, Chinese sales of children’s picture books to the U.S. grew by more than 180 percent during the period 2000-2005, with an average increase of more than 35 percent per year. Today, 50 percent of the children’s picture books printed on coated paper and sold in the U.S. are printed in China.

A second area of concern is the voracious appetite of the Chinese printing and paper industry for market pulp, and the effects of that pulp production on exporting countries. Though China does have its own pulp industry, the volumes of paper demanded by printing in China will outstrip internal pulp-making capacity for at least a decade, according to a 2005 CIFOR report by Barr and Demawan on China’s plantation-based wood-pulp industry. At present, China’s top six pulp supplying countries are Canada (20% of total imports), Indonesia (18%), Brazil (14%), Russia (14%), the U.S. (11%), and Chile (10%).

Some of these countries adhere to rigorous national forest management standards, and others simply do not. Some, such as Chile, have a well-established, size-stable base of sustainable plantation forests, and have in place well-document commitments not to harvest native forests In other countries, such as Indonesia, the demand for increasing quantities of pulp is driving continued conversion of natural forests to plantations. This conversion continues despite temporary regional moratoriums and national “cease-conversion” deadlines that never seem to be set in stone. (The report brochure contains a discussion, from RAN’s perspective, of the many issues surrounding forestry in Indonesia. The document is available in PDF format here (1.3Mb).

But just how did RAN identify the Indonesian fiber content in these children’s picture books? It relied on the same sort of fiber analysis performed for U.S. paper manufacturers when investigating a customer’s paper claim. And it used one of the very same facilities the industry uses, the Integrated Paper Services (IPS) laboratory in Appleton, Wisconsin.

RAN randomly selected three children’s books from each of the ten top U.S. children’s book publishers. All of the books were printed in color, and all were printed on coated paper and manufactured in China. Between November 2009 and April 2010, the 30 books were analyzed to determine if they contained tropical wood content, including species that occur in natural tropical forests (known in the trade as “mixed tropical hardwoods” or MTH) and plantation-grown acacia.

Eighteen of the 30 books tested positive for significant percentages of tropical wood content. In each of these 18 positive samples, acacia fiber was present. In four of the 18 positive samples, MTH fiber also was found.

According to Lafcadio Cortesi, Forest Campaign Director for RAN, the research did not include DNA testing that might have been used to determine the specific clone of acacia used to make the paper. And, because the study pre-dated the phase in of Lacey Act documentation provisions, a comparison of fiber found with stated fiber content could not be performed.

RAN has not yet announced any plans for public days of action based on the findings of the report, but it is likely that the ENGO will to focus some behind-the-scenes efforts to convince major U.S. publishers to use their purchasing power to influence the paper-procurement decisions of domestic and offshore printers alike.

ainforest Action Network’s recent analysis of the paper used in children’s books published by the top-ten U.S. children’s book publishers revealed that 90% of these publishers had published at least one in three books on paper containing tropical wood fibers linked to the clearing and conversion of Indonesia’s rainforests.

This is disturbing on a number of levels. The first is that of printing jobs being sent offshore. The books sampled for the RAN study, all “U.S. titles,” were printed in China. That should come as no surprise, as North American publishers increasingly have been outsourcing their printing to China for some time.

According to Joe Webb’s 2005 study, costs is the driving factor here, as Chinese printers can produce projects at as much as 30-50 percent savings over domestic sources. Lower labor costs, newer equipment, and, at times, subsidized paper costs contribute to these savings. According to the United Nations Commodity Trading Database, Chinese sales of children’s picture books to the U.S. grew by more than 180 percent during the period 2000-2005, with an average increase of more than 35 percent per year. Today, 50 percent of the children’s picture books printed on coated paper and sold in the U.S. are printed in China.

A second area of concern is the voracious appetite of the Chinese printing and paper industry for market pulp, and the effects of that pulp production on exporting countries. Though China does have its own pulp industry, the volumes of paper demanded by printing in China will outstrip internal pulp-making capacity for at least a decade, according to a 2005 CIFOR report by Barr and Demawan on China’s plantation-based wood-pulp industry. At present, China’s top six pulp supplying countries are Canada (20% of total imports), Indonesia (18%), Brazil (14%), Russia (14%), the U.S. (11%), and Chile (10%).

Some of these countries adhere to rigorous national forest management standards, and others simply do not. Some, such as Chile, have a well-established, size-stable base of sustainable plantation forests, and have in place well-document commitments not to harvest native forests In other countries, such as Indonesia, the demand for increasing quantities of pulp is driving continued conversion of natural forests to plantations. This conversion continues despite temporary regional moratoriums and national “cease-conversion” deadlines that never seem to be set in stone. (The report brochure contains a discussion, from RAN’s perspective, of the many issues surrounding forestry in Indonesia. The document is available in PDF format here (1.3Mb).

But just how did RAN identify the Indonesian fiber content in these children’s picture books? It relied on the same sort of fiber analysis performed for U.S. paper manufacturers when investigating a customer’s paper claim. And it used one of the very same facilities the industry uses, the Integrated Paper Services (IPS) laboratory in Appleton, Wisconsin.

RAN randomly selected three children’s books from each of the ten top U.S. children’s book publishers. All of the books were printed in color, and all were printed on coated paper and manufactured in China. Between November 2009 and April 2010, the 30 books were analyzed to determine if they contained tropical wood content, including species that occur in natural tropical forests (known in the trade as “mixed tropical hardwoods” or MTH) and plantation-grown acacia.

Eighteen of the 30 books tested positive for significant percentages of tropical wood content. In each of these 18 positive samples, acacia fiber was present. In four of the 18 positive samples, MTH fiber also was found.

According to Lafcadio Cortesi, Forest Campaign Director for RAN, the research did not include DNA testing that might have been used to determine the specific clone of acacia used to make the paper. And, because the study pre-dated the phase in of Lacey Act documentation provisions, a comparison of fiber found with stated fiber content could not be performed.

RAN has not yet announced any plans for public days of action based on the findings of the report, but it is likely that the ENGO will to focus some behind-the-scenes efforts to convince major U.S. publishers to use their purchasing power to influence the paper-procurement decisions of domestic and offshore printers alike.

ainforest Action Network’s recent analysis of the paper used in children’s books published by the top-ten U.S. children’s book publishers revealed that 90% of these publishers had published at least one in three books on paper containing tropical wood fibers linked to the clearing and conversion of Indonesia’s rainforests.

This is disturbing on a number of levels. The first is that of printing jobs being sent offshore. The books sampled for the RAN study, all “U.S. titles,” were printed in China. That should come as no surprise, as North American publishers increasingly have been outsourcing their printing to China for some time.

According to Joe Webb’s 2005 study, costs is the driving factor here, as Chinese printers can produce projects at as much as 30-50 percent savings over domestic sources. Lower labor costs, newer equipment, and, at times, subsidized paper costs contribute to these savings. According to the United Nations Commodity Trading Database, Chinese sales of children’s picture books to the U.S. grew by more than 180 percent during the period 2000-2005, with an average increase of more than 35 percent per year. Today, 50 percent of the children’s picture books printed on coated paper and sold in the U.S. are printed in China.

A second area of concern is the voracious appetite of the Chinese printing and paper industry for market pulp, and the effects of that pulp production on exporting countries. Though China does have its own pulp industry, the volumes of paper demanded by printing in China will outstrip internal pulp-making capacity for at least a decade, according to a 2005 CIFOR report by Barr and Demawan on China’s plantation-based wood-pulp industry. At present, China’s top six pulp supplying countries are Canada (20% of total imports), Indonesia (18%), Brazil (14%), Russia (14%), the U.S. (11%), and Chile (10%).

Some of these countries adhere to rigorous national forest management standards, and others simply do not. Some, such as Chile, have a well-established, size-stable base of sustainable plantation forests, and have in place well-document commitments not to harvest native forests In other countries, such as Indonesia, the demand for increasing quantities of pulp is driving continued conversion of natural forests to plantations. This conversion continues despite temporary regional moratoriums and national “cease-conversion” deadlines that never seem to be set in stone. (The report brochure contains a discussion, from RAN’s perspective, of the many issues surrounding forestry in Indonesia. The document is available in PDF format here (1.3Mb).

But just how did RAN identify the Indonesian fiber content in these children’s picture books? It relied on the same sort of fiber analysis performed for U.S. paper manufacturers when investigating a customer’s paper claim. And it used one of the very same facilities the industry uses, the Integrated Paper Services (IPS) laboratory in Appleton, Wisconsin.

RAN randomly selected three children’s books from each of the ten top U.S. children’s book publishers. All of the books were printed in color, and all were printed on coated paper and manufactured in China. Between November 2009 and April 2010, the 30 books were analyzed to determine if they contained tropical wood content, including species that occur in natural tropical forests (known in the trade as “mixed tropical hardwoods” or MTH) and plantation-grown acacia.

Eighteen of the 30 books tested positive for significant percentages of tropical wood content. In each of these 18 positive samples, acacia fiber was present. In four of the 18 positive samples, MTH fiber also was found.

According to Lafcadio Cortesi, Forest Campaign Director for RAN, the research did not include DNA testing that might have been used to determine the specific clone of acacia used to make the paper. And, because the study pre-dated the phase in of Lacey Act documentation provisions, a comparison of fiber found with stated fiber content could not be performed.

RAN has not yet announced any plans for public days of action based on the findings of the report, but it is likely that the ENGO will to focus some behind-the-scenes efforts to convince major U.S. publishers to use their purchasing power to influence the paper-procurement decisions of domestic and offshore printers alike.

ainforest Action Network’s recent analysis of the paper used in children’s books published by the top-ten U.S. children’s book publishers revealed that 90% of these publishers had published at least one in three books on paper containing tropical wood fibers linked to the clearing and conversion of Indonesia’s rainforests.

This is disturbing on a number of levels. The first is that of printing jobs being sent offshore. The books sampled for the RAN study, all “U.S. titles,” were printed in China. That should come as no surprise, as North American publishers increasingly have been outsourcing their printing to China for some time.

According to Joe Webb’s 2005 study, costs is the driving factor here, as Chinese printers can produce projects at as much as 30-50 percent savings over domestic sources. Lower labor costs, newer equipment, and, at times, subsidized paper costs contribute to these savings. According to the United Nations Commodity Trading Database, Chinese sales of children’s picture books to the U.S. grew by more than 180 percent during the period 2000-2005, with an average increase of more than 35 percent per year. Today, 50 percent of the children’s picture books printed on coated paper and sold in the U.S. are printed in China.

A second area of concern is the voracious appetite of the Chinese printing and paper industry for market pulp, and the effects of that pulp production on exporting countries. Though China does have its own pulp industry, the volumes of paper demanded by printing in China will outstrip internal pulp-making capacity for at least a decade, according to a 2005 CIFOR report by Barr and Demawan on China’s plantation-based wood-pulp industry. At present, China’s top six pulp supplying countries are Canada (20% of total imports), Indonesia (18%), Brazil (14%), Russia (14%), the U.S. (11%), and Chile (10%).

Some of these countries adhere to rigorous national forest management standards, and others simply do not. Some, such as Chile, have a well-established, size-stable base of sustainable plantation forests, and have in place well-document commitments not to harvest native forests In other countries, such as Indonesia, the demand for increasing quantities of pulp is driving continued conversion of natural forests to plantations. This conversion continues despite temporary regional moratoriums and national “cease-conversion” deadlines that never seem to be set in stone. (The report brochure contains a discussion, from RAN’s perspective, of the many issues surrounding forestry in Indonesia. The document is available in PDF format here (1.3Mb).

But just how did RAN identify the Indonesian fiber content in these children’s picture books? It relied on the same sort of fiber analysis performed for U.S. paper manufacturers when investigating a customer’s paper claim. And it used one of the very same facilities the industry uses, the Integrated Paper Services (IPS) laboratory in Appleton, Wisconsin.

RAN randomly selected three children’s books from each of the ten top U.S. children’s book publishers. All of the books were printed in color, and all were printed on coated paper and manufactured in China. Between November 2009 and April 2010, the 30 books were analyzed to determine if they contained tropical wood content, including species that occur in natural tropical forests (known in the trade as “mixed tropical hardwoods” or MTH) and plantation-grown acacia.

Eighteen of the 30 books tested positive for significant percentages of tropical wood content. In each of these 18 positive samples, acacia fiber was present. In four of the 18 positive samples, MTH fiber also was found.

According to Lafcadio Cortesi, Forest Campaign Director for RAN, the research did not include DNA testing that might have been used to determine the specific clone of acacia used to make the paper. And, because the study pre-dated the phase in of Lacey Act documentation provisions, a comparison of fiber found with stated fiber content could not be performed.

RAN has not yet announced any plans for public days of action based on the findings of the report, but it is likely that the ENGO will to focus some behind-the-scenes efforts to convince major U.S. publishers to use their purchasing power to influence the paper-procurement decisions of domestic and offshore printers alike.

About Peter Nowack

© 2025 WhatTheyThink. All Rights Reserved.