(This article originally appeared on Inkjet Insight.)

Everyone loves a productive press. With inkjet vying to take more volume away from traditional presses, color and image quality are yesterday’s problem. Today, the challenge is to go faster and faster. But what does it take to get that next bit of incremental productivity out of an inkjet press?

To answer that question, I reached out to a range of OEMs and many of them kindly responded in time for this article. Experts from Canon, Kodak, Kyocera Document Solutions, and Ricoh contributed to this article.

In this series, we will take deep dive into the many tradeoffs in the quest to make inkjet presses run faster and the different challenges faced when bringing sheet fed devices to market. For purposes of this discussion, we are talking about CMYK production inkjet presses using water-based inks serving the document market rather than the broader industrial/packaging market which has many more substrates and ink chemistries to consider.

Making Inkjet Go Fast

It’s important to note that “fast” inkjet is about overall productivity. An ultra-fast press that requires maintenance for 25% of every shift is equivalent to a press that runs at 80% of the speed and requires 20% of the maintenance.

Inkjet development is plagued by the law of unintended consequences. Many of the levers that inkjet OEMs have at their disposal to make a press go faster come with consequences in the form of increased machine price, running cost, reduced control of dot formation, reliability, and media compatibility.

Everyone is in general agreement about the different levers available but how those levers are “pulled” depends on the market being served, the level of commitment to a particular printhead technology (piezoelectric, thermal, continuous), and whether the press is roll or sheetfed.

At the fundamental level there are five key ingredients: printheads, inks, drying, transport, and the electronics to make them all work together. When you dig into each of these areas, there are lot of nitty gritty details on material science, aerodynamics (it is rocket science!), and electrical engineering that get complicated fast. Let’s start with the relevant characteristics of printhead technology.

Heads and Nozzles and Drops, Oh My!

When considering printheads, an OEM needs to consider the size of the drop(s), drop uniformity, and drop firing frequency. The first thing that may come to mind is that if you want to make the press go faster, fire the drops faster. An OEM may be able to make some level of change to the drop firing frequency through changes in electronics, but significant changes may require a smaller drop size (less volume to fire). However, a smaller drop size may not deliver the same coverage as the previous requiring more nozzles to deliver the same result. More nozzles require more complex controllers and, of course, more cost.

Todd Potrykus, Senior Program Manager, HPS Global Product Marketing with Ricoh weighed in, “Making inkjet go faster is largely a matter of a cost/benefit analysis: at what point does the target functionality become too expensive for the market?” He noted that while the frequency of an individual head is a limitation there is nothing (except cost) to prevent an OEM from combining multiple heads with different firing sequences to achieve a higher speed. For Ricoh’s recently launched Pro VC80000, he shared, ”We have taken advantage of increased firing frequency to maintain resolution at a higher speed—without the expense of multiplying heads. We have also introduced temperature control to the heads to ensure that we have jetting stability even at the higher speeds.”

In assessing the tradeoff in adding more printheads to increase speed (or resolution), both the cost and the longevity of the printhead need to be considered. While HP makes both piezo and thermal heads, they use piezo and UV inks on flatbed presses and exclusively HP thermal printhead technology for their highspeed production inkjet presses. Thermal inkjet heads be 10 to 20% of the cost of piezo heads so many more heads per inch can be justified. In addition to redundancy, this can enable multiple drop sizes. Thermal heads have also yielded a shorter useful life than piezo but not enough to counterbalance the cost differential. In fact, thermal lifespan has been consistently increasing. Notably, Canon’s latest press announcements will leverage Canon’s thermal inkjet technology while their existing product portfolio will continue to leverage Kyocera piezo technology, but with fewer differentiated drop sizes than previous generations.

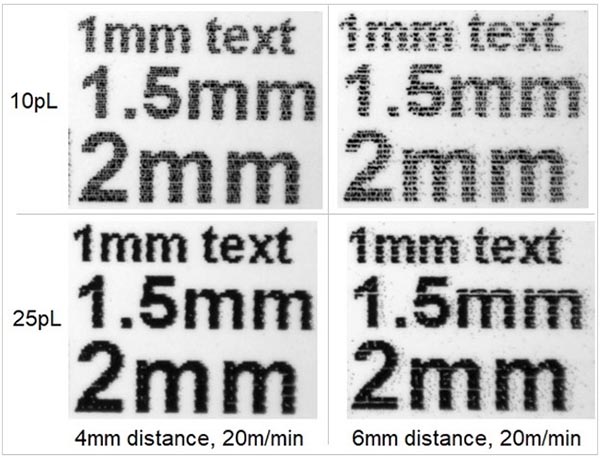

Randy Vandagriff, Senior Vice President, Print at Eastman Kodak Company, warns that there is a practical limit to the smallest drop landing on the media. “As drops get smaller, drop momentum decreases, meaning the nozzle plate needs to be closer to the paper, increasing the risk for head strikes and jet outs, and greatly affecting productivity,” he said. “Eventually it will be impractical to get close enough to a web running at high speeds.”

Kodak has the distinction of being the only OEM offering continuous inkjet printheads, a technology I covered in depth in a previous article. Vandagriff notes that, “Kodak’s unique Continuous Inkjet Technology has demonstrated the ability to generate different print drop sizes at the same frequencies. This enables Kodak to modulate its drop size based on resolution and speed without the addition of more nozzles.” Kodak says that they have demonstrated the ability of their fundamental technology to have drop frequencies that are twice as high as today’s, approaching frequencies of 800 kHz.

The velocity of the drop and the distance it must travel also impact the ability to increase speed. Fast moving transports create wind resistance. Smaller drops require higher velocity, shorter throw distance, or both to avoid developing satellites and other defects that will impact image quality.

Example of reduced jetting accurate and increased satellites at higher throw distance. Source: Mark Bale ©Inkjet Academy.

Piezoelectric printheads generally support a shorter throw distance than either thermal or continuous printheads. This makes it more complex for piezo heads to shift from thin to thick media and may constrain the media range.

Vandagriff says, “Drops generated [from Kodak CIJ heads] have much higher drop momentum, allowing for the nozzles and printheads to be further from the substrate.”

Since resolution demands have been increasing along with the push for more speed and greater substrate support, getting more out of printheads requires putting more demands on electronics.

Dr. Martin Berg, Product Line Manager Continuous Feed Inkjet with Canon, says, “Printheads can be modified/developed to get a larger operating window with respect to ink throughflow. The jetting speed of the printhead can be optimized by nozzle design and driving electronics.” Berg notes that the electronics, in terms of data handling and raster performance are currently a barrier. While electronics in general are getting cheaper every year, press controller architectures must be able to scale to adapt to increasing data demands.

Inkjet printheads are meaningless without something to jet and the chemical composition, viscosity and overall complexity of the ink have an impact on suitability and productivity. In our next installment we will talk about ink and drying choices of various OEMs as well as the distinct challenges of sheetfed inkjet presses.