Last month saw the Census Bureau’s release of the Quarterly Services Survey, which includes some of the biggest print-buying markets, such as publishing and advertising.

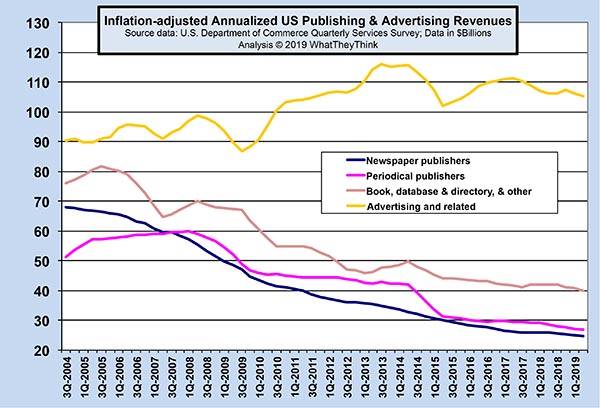

On an annualized basis, since 2004, newspaper publishing revenues have dropped by about $43 billion, although for the past three years the drop in revenues hasn’t been quite as steep as earlier in the decade—or in the previous decade. Periodical and book publishers are in only slightly better shape.

Advertising revenues have been up and down, which is reflective of the fact that the nature of “advertising” is changing. It used to be easy to spot the ad: a page in a newspaper or magazine, a radio or TV commercial, etc. But over the period encompassed by this chart, we’ve seen not just a shift to non-print forms of advertising, but other kinds of marketing initiatives than what we usually think of as “advertising.” Think of content marketing (white papers and sponsored “advertorial”), e-newsletters, mobile apps, and other kinds of initiatives. With this kind of “advertising,” more work is done internally or by freelancers rather than by agencies, and offer much more bang for much less buck. There is also a greater reliance on social media, which is largely the purview of PR agencies/reps (hence the reason that PR employment tends to be consistently higher than other creative markets) or even internal social media managers.

We focus here on print, but when we talk about advertising, we also have to include TV and cable; terrestrial TV audiences are shrinking, people are increasingly cutting the cord, and streaming is the “new cable”—and largely advertising-free. (People happily pay an extra $5–6 for Hulu’s commercial-free service, for example, and Netflix is ad-free, as well.) And pre-roll ads on YouTube rarely survive Skip Ad.

Savvy publishers have been able to succeed with new business models that leverage online and print, and have been able to think beyond the paywall and the print ad.