October 22, 2004 - Dynamic Inertia: The Risk of Organizational Paralysis - Economic Insight - Does Alan Greenspan Read “Fridays with Dr. Joe”? - Ask Dr. Joe Dynamic Inertia: The Risk of Organizational Paralysis The recent Creo news made me think about how difficult it can be as an employee in a company in turmoil. I seemed to excel at that when I had a “regular job.” As an employee, it’s often hard to keep your mind on what you’re supposed to be doing and not get swallowed up by the swirling vortex of uncertainty and cynicism caused by out-of-context news and industry buzz. Usually the “whole story” takes months to emerge, and often has many surprises. This is one of those situations, and there are many like this going on all the time: Heidelberg is reorganizing, Goss is reconstituting, Agfa’s graphic group has a new leader. (Lest someone think I am picking on them, there are more, but my official word count constraint does not allow me to mention them all.) Even a firm that’s holding its own and even expanding may need to adjust itself in ways that can be uncomfortable or unsettling for employees. When business is booming, these events are easier to digest; it’s when business is sluggish or meandering that these issues cause more concern. Under these circumstances, organizations can seem to be paralyzed. It’s hard to get meetings scheduled, difficult to secure approvals, and sometimes hard to function because the attention of top executives is consumed in managing these disruptive events. These situations are hard on CEOs, too, but that’s part of the challenge that makes CEO jobs so interesting and attractive. An old boss of mine used to describe company turmoil as dynamic inertia. It looks like a lot is going on, but nothing is really happening. If the executive’s job is to create change, then they must learn how to to break out of this paralysis and move forward. Paralyzed companies miss opportunities because they’re preoccupied. Creating change requires teaching people not just to embrace change, but to create it; not to cling to issues and events that don’t really matter, but to progress with the issues and events that matter to clients, customers, and prospects. Getting out of—and preventing—the inertia is the CEO’s job. Strangely enough, part of the CEO’s job is to “run blocking” to keep outside forces from unnecessarily affecting the business. Back to top -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Economic Insight The economy is still strong. Last week, it was reported that retail sales rose 1.5% in September, above expectations, the biggest gain since March. There was a 4.2% increase in auto sales, a segment that had been sluggish for the past few months. I always like the analysts who say, “The report wasn’t that good because auto sales were up,” because they were the same analysts who were so dour when auto sales were down. For some reason, auto sales are important only when they are down, but when they are up, they distort the economic picture. I’m glad I’m only a pretend economist. There were also some reports about the trade deficit. I wish they’d just stop. There is so much not counted in the trade data that it’s not worth losing sleep over. The dollars out have to be repatriated to have true value, and they usually end up being invested here. I was perusing my bookshelf the other day, and I saw “The Witch Doctor of Wall Street” by economist Robert Parks (published in 1996 and still available from amazon.com and other retailers). I remember it was the first book that rattled me, because even though I knew a lot about economics, I was still easy prey for media economic reporting. It can be a tough read, and while I might disagree with some occasional analysis in the book, it certainly does make you think and re-evaluate your assumptions. That’s why I still keep it on my shelf. It’s entertaining when he discusses being pressured to make good comments about companies while he was at various brokerage firms. Often those companies didn’t deserve the praise, but the folks on the broker side wanted their business. He has particular disdain for protectionism, especially for those who claim they want free markets but find a way to claim “our industry is different” and supposedly deserves protection. I’m surprised this book isn’t cited more often. I had the opportunity to check the latest difference between the payroll survey of employment and the household survey, a continuing topic in this column. The difference is now 3.4 million workers that the payroll survey does not account for. Self-employment and small business are alive and well, except at the Bureau of Labor Statistics, I guess. Last week I suggested to those who count my words when preparing this column that every time I use the phrase “payroll survey,” it should not be part of my word count limit. If the BLS can ignore workers, I should be able to designate phrases that should not be counted in my word target, as well. It’s only fair. Though I did lose the “argument.” Back to top -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Does Alan Greenspan Read “Fridays with Dr. Joe”? :-) I’m frequently kidded about how some comment shows up in this column and then a WTTer sees it repeated in the newspaper or by a TV talking head. This most recent one was funny because it was Alan Greenspan talking about the inflation-adjusted price of oil, as I did last week and have on several past occasions. I know Mr. Greenspan has a lot more interesting things to do than read this column. But it is funny, and at a minimum, warms one’s heart to know that I can potentially make the same misjudgments that he can. It’s just that when I do them, they’re mostly inconsequential to the economy as a whole. On the Web Back to top -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Ask Dr. Joe Q: I am a new member to the site, and wanted to hear your views on the possible negative aspects of ROI. Much as been made recently of the entire ROI phenomenon and all I can find so far are articles pushing ROI in business and especially in advertising. Do you have any credible information on the negative aspects of this ROI trend? A: There are several problems. First, there is no agreed-upon measure of ROI for advertising except in direct mail where it usually relates to the percentage of orders or average order size that results from a mailing. As far as other forms of advertising, there are no good measures at all. A comparative increase in awareness, measured by research done before and after the advertising, is sometimes used, as is judging whether or not there was an increase in sales. None of these are as straightforward as they seem. Awareness does not always translate into sales. And sales can be stimulated by other factors, including competitive activity (such as shortages of a competitive product, or other factors, such as hot weather encouraging sales of soft drinks, whether or not an ad campaign was in place at the time). Most importantly, the demand for instant results undermines the efforts to develop strong corporate branding, replacing it with short term promotions. For example, one can nearly always stimulate sales by cutting prices. In the long run, buyers learn to wait for sales rather than buying at any other time. If your desire is to create an image of luxurious quality, having a higher price communicates that quality to the buyer. Those pricing efforts are useless if stimulating sales in the near term is done via price promotions. The other thing an ROI obsession can do is to force the selection of media inappropriate to the task. Trade shows take a long time to plan and are expensive. But done correctly, they lower the total cost of sales, and increase revenues. The benefits of trade shows can take months to realize, and the judgment of their ROI is not always possible. An Internet promotion can be measured in just days. Finally, corporate image is an important part of goodwill. We know that goodwill is important because people are willing to pay for it. That is, a company’s reputation has value when the company is purchased. Goodwill is built up over a long period of time, and you don’t know the value of it until the business is sold. So it is impossible to calculate an ROI for efforts to build goodwill until you no longer own the business! While measuring ROI is shortsighted or incomplete at best in many situations, advertisers do need a way to determine whether or not they are getting good value for their investments in advertising and promotion. What I am saying is that being obsessed with ROI creates a myopic view of the long term effects of advertising and promotion, creating a short-term management focus that is counterproductive. Perhaps it’s best described as managers needing to keep two conflicting ideas in their heads: the short term trade-off of ROI, and the concept of “brand equity.” Like a stock, you can get vast swings when you are looking at ROI alone, but when you look at long term performance, certain companies really stand out and seem to be impervious to the quarter-to-quarter mentality. Another analogy. When I watched baseball in the 1960s and 1970s, pitchers were taught how to “pitch” and get through situations, and how to change what they did as they got tired. Today, pitchers are on pitch counts and told to throw as hard as they can as long as they can. Complete games with one pitcher were common in the 1960s and 1970s. They are very uncommon now. Yet I can’t say that the pitching is any better or that careers have really been extended with this new philosophy. ROI obsession is like today’s pitching. Maybe it’s a cultural thing. But I miss the old style of pitching where there was some intestinal fortitude and thinking required to still be on the mound at the end of the game. Back to top

Commentary & Analysis

FREE: Dynamic Inertia, Economic Insight, Alan Greenspan, and Ask Dr. Joe

October 22,

About Dr. Joe Webb

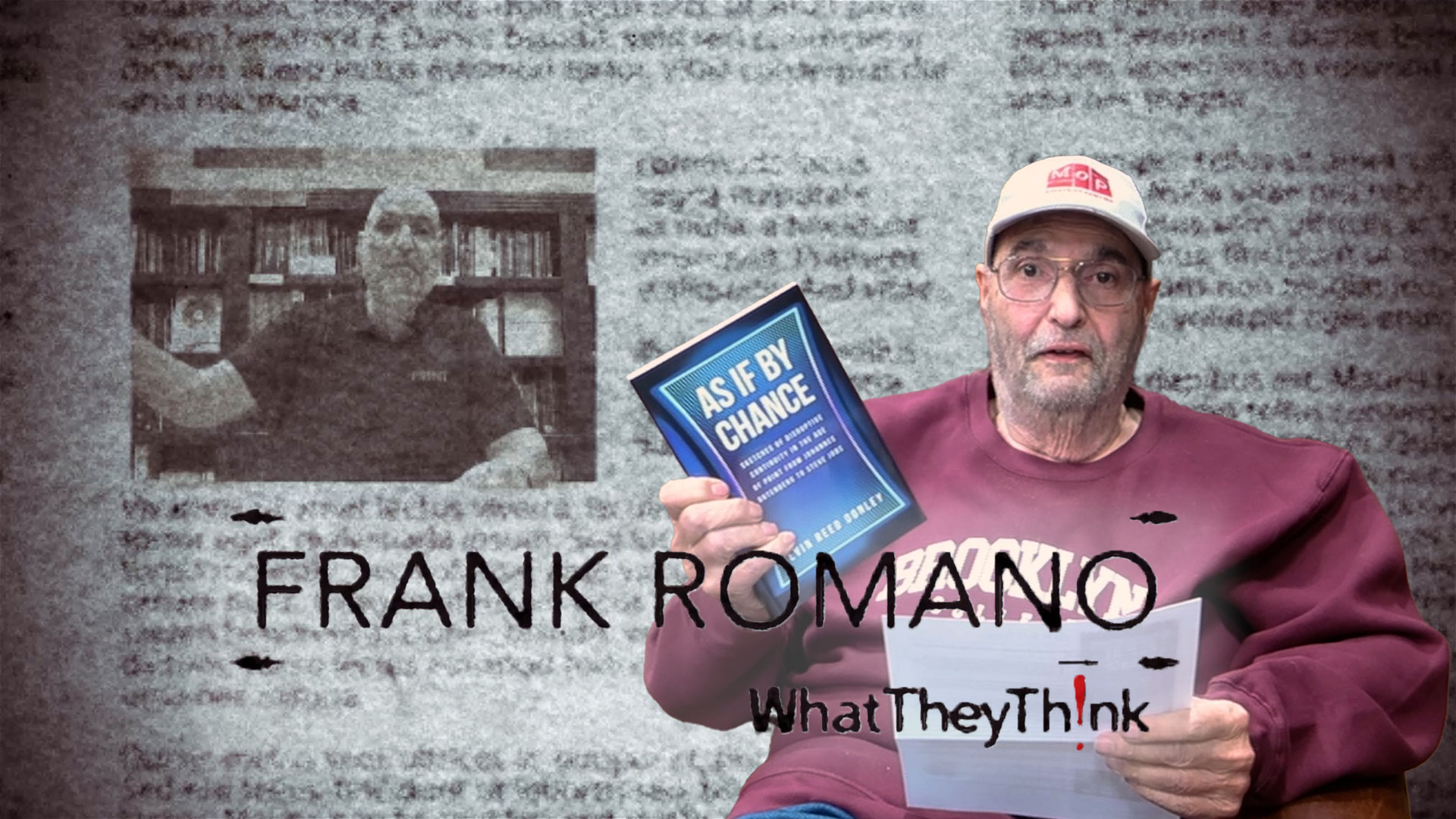

Dr. Joe Webb is one of the graphic arts industry's best-known consultants, forecasters, and commentators. He is the director of WhatTheyThink's Economics and Research Center.

Video Center

WhatTheyThink is the official show daily media partner of drupa 2024. More info about drupa programs

© 2024 WhatTheyThink. All Rights Reserved.