The current fashion system uses high volumes of non-renewable resources to produce clothes that are used only for a short period of time before they are incinerated or placed in landfills.

This was a year of recovery for textiles and apparel as supply chain issues (still a problem) began to settle a bit, and suppliers were back online after the pandemic. Consumers were also buying—both online and back in-stores, which is good news for brands.

Sustainability is still a key issue for the industry, however incremental progress is being made. Some brands are all in, such as Patagonia.

The company has long been known as one of the earliest clothing companies to put sustainability at the top of the list, from its inception, actually. In case you missed it, Patagonia founder Yvon Chouinard, a billionaire, is giving the entire company away to fight the Earth’s climate devastation.

Decision-making authority has been given to a trust that will oversee the company’s mission and values. That trust controls 2% of the stock. The other 98% of the company’s stock will go to a non-profit called the Holdfast Collective, which will use every dollar received to fight the environmental crisis, protect nature and biodiversity and support thriving communities.

Each year, the money Patagonia makes after reinvesting in the business will be distributed to the non-profit to help fight the environmental crisis. But they are an exception on the producer side.

Patagonia is still in the minority as they take on sustainability issues.

Too many companies are still focused on fast fashion and ephemeral trends. This has many deleterious effects on the environment—and is actually bad for the industry itself.

We see proof that going after revenue based on short-term self-interest is to no one’s long-term benefit. Clothing is typically made overseas using labor that isn’t treated well. Brands negotiate tough pricing that gives them the best margins while making it tough for their suppliers to stay in business. Plus, a lot of that “stuff,” which none of us really needs, ends up in the landfill.

“Globally, an estimated 92 million tons of textile waste is created each year, and the equivalent to a rubbish truck full of clothes ends up in landfill sites every second,” according to recent data from BBC. “By 2030, we are expected as a whole to be discarding more than 134 million tons of textiles a year.”

The story states that the current fashion system uses high volumes of non-renewable resources to produce clothes that are used only for a short period of time before they are incinerated or placed in landfills. And with 60% or more of the fabric content coming from fossil fuel feedstocks, these materials will stay in those landfills basically forever. So they use non-renewable resources that are wasted when the garment is worn once or twice and then thrown away.

We can certainly blame the brands for this behavior, and we should. But consumers also need to play a strong role in driving change in this trend. If no one is buying the stuff, it doesn’t matter how cheaply it is made, the brands will ultimately be forced to change their business practices. It will take time, though.

Sustainable Fibers

That being said, many suppliers to the industry are working hard to develop more sustainable feedstocks. We expect to see this accelerate in 2023 and beyond, bringing the volume of these materials to a critical mass that can make a difference. Here are just a few examples.

Lycra

One interesting project is underway at Lycra, perhaps better known by its generic names, spandex or elastane.

Back in the day, your jeans were probably 100% cotton. But as we saw waistlines expanding and consumers looking for more comfort in the form of stretchy fabric, you would probably be hard pressed to find jeans that don’t contain some percentage of spandex. Comfortable, yes. Sustainable, not really.

QIRA, a new fiber from Lycra, will use feedstocks from field corn grown by Iowa farmers, and consists of a next-generation 1,4-butanediol (BDO) as a primary ingredient.

BDO is a chemical commodity used to make polyesters, plastics and spandex fibers, but heretofore has come from petrochemical feedstocks.

The result is an estimated 70% of Lycra fiber derived from annually renewable feedstock, saving up to 93% of greenhouse gas emissions when replacing fossil fuel feedstocks. The company also notes this substitution maintains the high-quality performance consumers are used to with Lycra.

Biologic Feedstocks

Biologic feedstocks are increasingly being used as well, including vegan leather created from almost any fibrous plant material, with mushrooms being at the top of the list.

Companies like MycoWorks and MyForestFoods are active in this space, and we expect many others to join the fray in the coming year. Some brands are already adopting these vegan leathers, but again, it’s a very small percentage of the whole market.

Smartfiber AG has developed a fiber created from seaweed, which is processed and mixed with cellulose to create a plant-based yarn. To ensure sustainability without over harvesting, producers harvest a crop every four years, giving the plants time to regrow. The plant is naturally dried, chopped and added to the cellulose.

It does use chemicals, but in a closed-loop process that does not release chemicals into the environment, as is the case with many other chemical-based processes. The fiber biodegrades and is compostable.

Brands and fabric manufacturers would be well-served to get in on the ground floor of these efforts. Maybe seaweed and mushrooms are not your thing, but there are plenty of other fiber types that do not use petrochemical feedstocks yet deliver the required performance.

In the case of mushroom leather, brands can do even more with it than they can with natural leather without the immense ecological impact of the traditional leather-making process, from pastures and cattle feed to a wide range of toxic chemicals used in the tanning process.

Greenwashing

Consumers also have a responsibility to look into manufacturer claims about their sustainability.

For example, PrettyLittleThing, a fast fashion brand, has made big waves about launching a fast fashion resale marketplace. This is perhaps to compete with reputable resale sites such as Real Real, Poshmark, ThredUp and DePOP. But the big splash only represents about 1% of revenues.

Speaking of online and in-store resale and rental sites, we expect those to continue to gain steam in 2023. As I speak especially to Gen-Zers, a growing component of the buying population, they are taking advantage of these sites.

One friend’s daughter has been in multiple weddings this past year and has used Real Real as the key source for bridesmaid dresses. These can be worn once and then popped back into the resale market for someone else to use, instead of ending up with a closet full of (often pretty ugly) bridesmaid dresses that will never be worn again. Wasn’t there a movie about that?

Another friend’s daughter has created her entire wardrobe using DePOP—buy, wear, sell back, buy something else, etc. The more these types of sites grow, the more pressure there will be on brands to change their business models.

Europe is way ahead of the U.S. in passing regulations that punish greenwashers, but even in the U.S. pressure is being placed on manufacturers across all industries that are putting forward false claims about their sustainability. As consumers, it is our responsibility to dig into the claims to validate their veracity and act accordingly.

Digitalization

We will increasingly see more digitalization of the entire supply chain in 2023 and beyond.

Digital textile printing continues to get faster, better and more affordable—especially when you look at the total life cycle cost. It enables companies like Raspberry Creek Fabrics and BMC.fashion to produce locally in smaller, highly customized runs with exquisite designs, eliminating all that back and forth of heavy fabric from Asia.

Cut-and-sew operations are popping up as well, including SAI-TEX in Los Angeles, BMC.fashion in Phoenix, Sonora Stitch Factory in Tucson, and North Carolina based Sparty Mill.

Again, these are just scratching the surface, but all are taking advantage of digital technologies, for design, production and for training, and helping reshore more of the textiles and apparel industry.

We should also mention the growing number of educational initiatives, such as ISAIC in Detroit, that are attracting new labor to the cut-and-sew business.

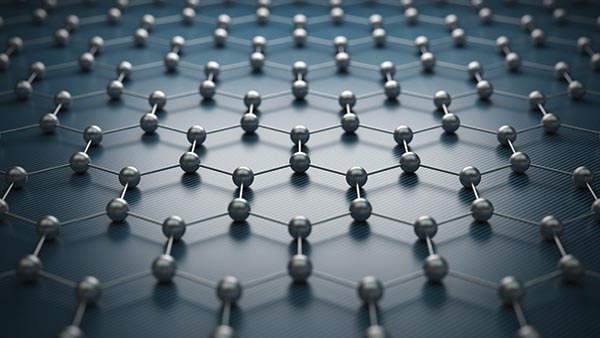

Graphene is Great

We can’t end this outlook without sharing news about Graphene and its increasing use in the textile industry. Why is this important? It goes back to getting rid of cheap, throwaway clothing and also making garments and other textile products more functional.

Graphene, whether covalently bonded into the fiber or used as a coating, has many properties that add value to fabric and apparel. This includes increasing strength, improved abrasion resistance, thermal and anti-microbial properties and conductive properties, the latter of which will be making huge contributions to functional fabrics and wearables.

Graphene, discovered in 2004, has made its way into a number of industries, and is now gaining traction in textiles, including textiles used in the auto industry. There are already graphene-enhanced products on the market, including in sportswear, protective gear and more.

So keep a look out for new developments here as we move into 2023 and beyond.

Graphene is increasingly used in the textiles industry.

Looking Ahead

Despite the reputation of the textiles and apparel industry as one of earth’s most prolific polluters, progress is being made, and the new technologies being developed by suppliers to the industry—as well as pressure from consumers—are two keys to turning this bad situation around.

It’s a huge industry. It won’t happen overnight. But we expect to see new initiatives chipping away at the traditional models in 2023 and beyond.

We all have a role to play, whether we are suppliers, manufacturers, brands, associations, journalists, consumers or upstart companies looking to make dramatic changes. So the question for you, dear reader, is: What’s in your closet?

Discussion

Only verified members can comment.