Quick: what’s the one form of printed matter that most of us are likeliest to have in our possession at any given moment of the day?

Paper currency. Greenbacks. Dead presidents. Singles, fins, and sawbucks. MarketWatch, an investment site, reports that despite the increasing use of electronic alternatives to cash, the volume of small bills in circulation has remained stable over the last 20 years. So entrenched are everyday transactions with paper currency that the Federal Reserve recently placed its largest order for $1 bills since 2010. (Singles, as the article notes, wear out the fastest and thus have to replaced more often than bigger bills.)

A bit surprising is the article’s assertion that young people (ages 18 to 24) prefer to use cash more often than their parents (45 to 64). Other factors, including household income, determine how, when, and by whom cash is exchanged for goods and services.

Underneath the statistics is our instinctive need for a tangible, portable, and tradable token of the wealth that belongs to us, whatever the “wealth” amounts to in real terms. Coinage has served the purpose since the first ones were minted on the Greek island of Aegina in the fifth or sixth century B.C. Folding money—paper bills—first came into use in China during the Tang Dynasty (A.D. 618-907). By the time the U.S. Treasury began issuing printed currency in 1862 to help the North pay for the Civil War, the identification of money with flat paper was complete.

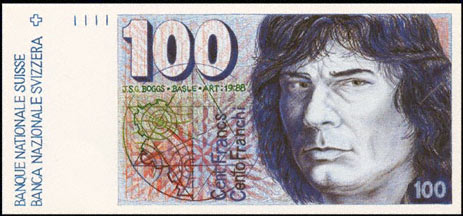

Nobody ever understood people’s hard-wired affinity for hard-copy currency better than J.S.G. Boggs. Boggs isn’t a Treasury official or a banknote printer—he’s an artist who has been creating fanciful replicas of paper money for the last 30 years. They’re perceived as such objects of beauty that Boggs has been able to finance his lifestyle by swapping “Boggs Bills” for the things he needs. This practice—not much different in concept, as far as this writer can see, from paying with bitcoin—has earned him both fame in the art world and notoriety among government anti-counterfeiting agencies. He’s been arrested and raided for doing it in this country, Australia, and the U.K.

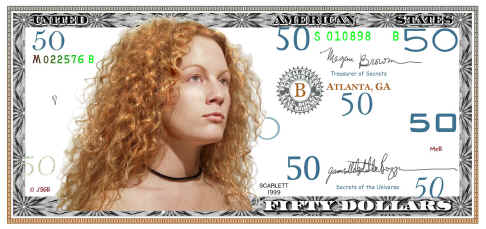

Examples of “Boggs Bills”

Boggs has said, “Most people make this mistake that my work is predominantly about money. And it’s really not... I want them to ask, ‘What is money, really?’ One of the reasons money fascinates me as an image is that money is so many different things all at the same time. It’s a work of art, it’s a medium of exchange, it’s a representation. In short, it’s a representational work of art that represents many different things.” He might have added that it’s also why we will never entirely give up using paper money no matter how much more convenient and secure the virtual currency in our digital wallets turns out to be.

Printed money (the everyday kind) keeps us as close as we keep it precisely because it’s printed. As Boggs knows, it hasn’t run out of ways to engage our imaginations—consider this application, in which a $5 bill was used as the trigger for an augmented reality experience on behalf of President Obama’s 2012 reelection campaign. The green stuff remains as enticingly green as ever, and you can take that to the bank.

Discussion

Join the discussion Sign In or Become a Member, doing so is simple and free