- Representatives from large paper mills generally felt that adapting papers that worked for both offset lithography and toner-based digital printing was relatively easy compared to inkjet.

- Offset papers are designed not to absorb water from an offset fountain solution. The rapid growth of inkjet has created a need for papers that won’t absorb a fountain solution but will absorb water-based inkjet inks.

- Inkjet-treated papers offer print service providers some assurance that the stocks will perform well for the applications that they print on their high-speed production color inkjet systems, but adding a pre-treatment increases the cost of the paper.

By Jim Hamilton

Introduction

Anyone who uses high-speed production color inkjet systems to produce documents knows that paper can be an issue, particularly for jobs that require glossy finishes and high coverage levels. System vendors and paper mills are working diligently to create effective strategies to address this issue. In a nutshell, these solutions can be distilled into two categories:

- Inkjet-treated papers

- Advanced inks and drying systems

This article, the first in a two-part series, will discuss the pros and cons of inkjet-treated papers. Next week’s piece will address advanced inks and drying systems.

The Perspective from Paper Mills

I recently had the opportunity to speak with a number of representatives from large paper mills about production color inkjet printing and the challenges it presents for them. In general, these representatives felt that adapting papers that worked for both offset lithography and toner-based digital printing was relatively easy compared to inkjet. Bear in mind, however, that offset inks and electrophotographic toners have something in common—in both cases, you are trying to press something (i.e., the inks or toners) into the paper. That model changes with inkjet.

Most inkjet printing systems use water-based inks that get sprayed onto the surface of the paper. The ink’s ability to adhere presents a vastly different scenario than offset inks or toners, particularly as it relates to drying the water associated with most inkjet inks for document applications. For years, paper mills made offset papers that were designed not to absorb water from an offset fountain solution. Now, because of the rapid growth of inkjet, they are trying to design papers that won’t absorb a fountain solution but will absorb water-based inkjet inks. It is easy to understand the frustration that paper mills must feel when faced with this monumental engineering challenge. It should therefore come as no surprise that when paper mills are asked about the ideal solution to this inkjet dilemma, they say it must come down to papers that are specially treated to function well with inkjet inks.

A treated paper is a stock that has been produced with a coating that enables inkjet inks to adhere well to the paper. Although these treatments are usually applied at the mill, they can also be applied at a separate location or even at the printing site. You can get an inkling of how this might work by looking into what HP introduced with its first high-speed color printing systems, now known at the HP PageWide Web Press series. These devices incorporated a row of inkjet heads whose sole purpose was to lay down a solution called a bonding agent just in the image areas. This is basically the same as treating the paper on the fly. Although this technique works well on lower coverage applications for uncoated papers, it struggles as coverage levels increase and is not particularly well-suited for coated papers. The treated papers that are sold by many mills apply a treatment akin to HP’s bonding agent, but the treatment is applied across the entire sheet as part of the paper manufacturing process.

Inkjet-treated papers offer print service providers some assurance that the stocks will perform well for the applications that they print on their high-speed production color inkjet systems. Although this is certainly appealing, the challenge is that adding a pre-treatment increases the cost of the paper. What’s more, print service providers generally need to stock two classes of paper—one for their offset presses and one for their inkjet systems. Although this scenario is not ideal, it does address the problem.

The Bottom Line

To summarize, here are the top pros and cons for water-based inkjet printing on treated papers:

- PRO: Strong results across all applications, including high-coverage jobs on coated papers

- CON: Increased cost in relation to comparable untreated papers

- CON: The need to stock two separate paper classes for offset and inkjet

- CON: May not work equally well for all inkjet ink formulations

This concludes my assessment of treated inkjet papers. Next week’s article will explore the case for advanced inks and dryers for production inkjet printing.

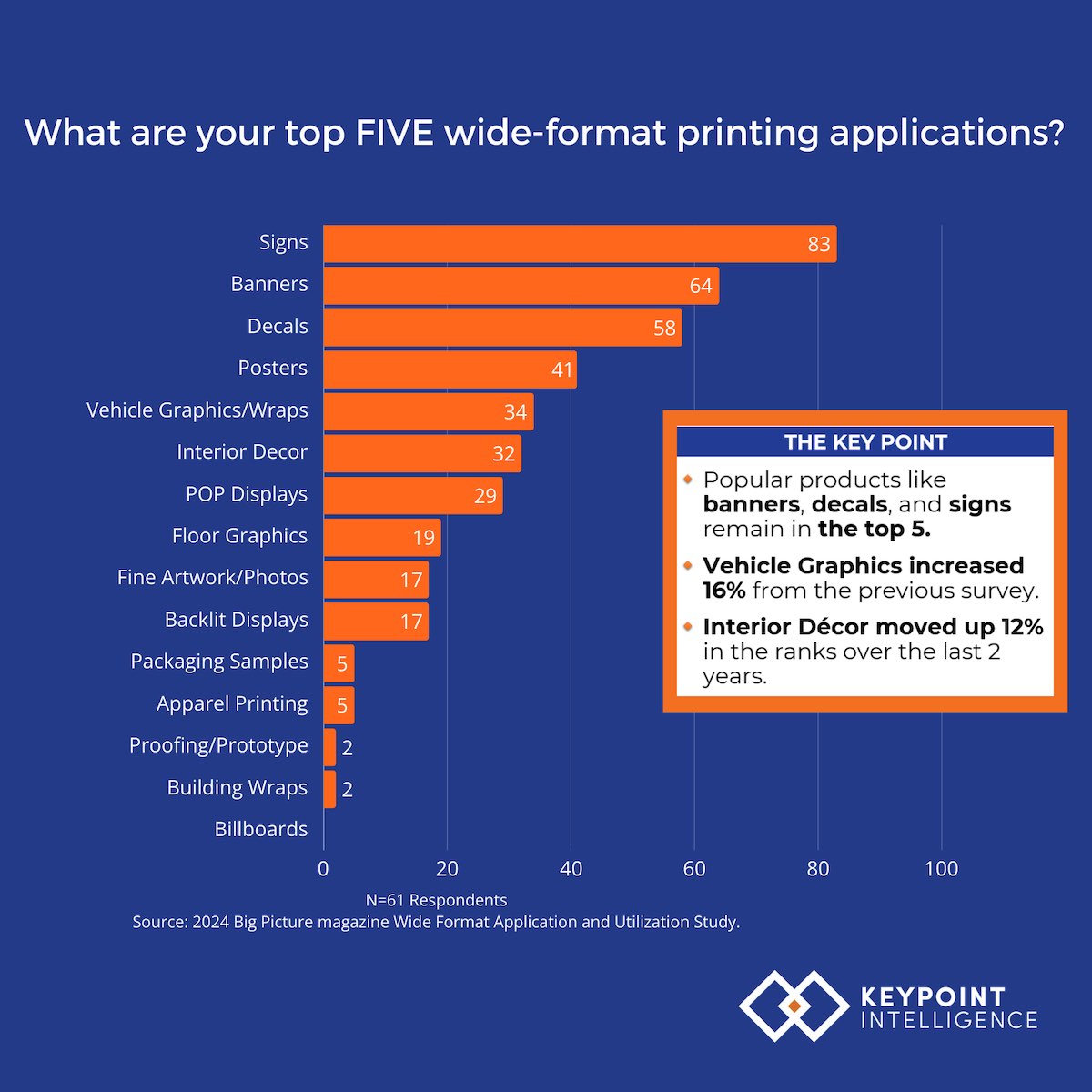

Jim Hamilton is a well-known industry analyst who serves as Consultant Emeritus for a number of Keypoint Intelligence – InfoTrends’ consulting services. He supports areas including production digital printing, wide format signage, labels & packaging, functional & industrial printing, production workflow & variable data tools, document outsourcing, digital marketing & media, and customer communications.