By Steve Aranoff & Robert FitzPatrick, The EAGLE October 31, 2006 -- The Eagle walked the floor of Graph Expo in Chicago and saw not just a vast mingling of salespeople, customers and products, but an elaborate series of rituals. These rituals are largely a legacy of the past and have not been critically examined. New forces in the marketplace, in finance and in technology raise the question about whether much of what we do at these annual shows is useful or even relevant now. The first installment of this series dealt with ritual selection of hotels and the occupation of large acreage on the showroom floor. It questioned the relevance today of a ritual gathering of only vendors and printers when print buyers are in fact the new “end-users,” the ones who control the destiny of print. They are not in attendance. These rituals were questioned when the new mission of shows is about leading customers into technologies they don’t know they need and some of which are not financially proven. Is the showroom floor the best place for educational selling or discussing complex new challenges facing the medium of print? This final part takes note of other strange rituals including press conferences that are actually advertisements, rumor mongering that overshadows millions spent on marketing and Wall Street finance that hovers above the show floor driving manufacturers into “innovation” and deciding who will survive and who will perish. Freedom the Press A time honored ritual of the annual graphic arts show is the press conference and the busy interviewing by the industry press corps. The news media in the graphic arts industry are officially treated as objective, fair and balanced and independent. Their attention is sought by all vendors. There is the appearance of a free press in the industry. Yet, the unspoken reality is that purchased advertising prevails over earned publicity in garnering press coverage and determining what gets reported and what is never written. The objective independence of the industry press corps is gently mocked the moment we arrive in the pressroom. Portfolios are handed out to carry around the show each bearing the prominent log of Adobe and name tag ribbons are hung around our necks with the word “Kodak’ repeated every few inches. We are sent on to the floor as billboards for major vendors whose advertising we are expected to embellish or at least dutifully reinforce. In the ritual of press conferences, the rooms are jammed with journalists for announcements by companies that purchase the most advertising from the publishers that the journalists represent. Kodak’s and HP’s meetings were standing room only, though they had no more substantive news announcements than other lesser known vendors. And, in keeping with the respect that their advertising volume gains, few questions are asked, and certainly nothing that would cause discomfort, like HP’s Boardroom troubles that are all over the world’s business press or Kodak’s struggles for reinvention. Contrast this with the Pitman Company press conference. As an independent, family owned company, Pitman’s continued financial stability in a consolidating industry is newsworthy. It is now the largest distributor in the largest market on earth, with arguably more customers in the printing trade than any other vendor on the show floor. As a distribution company, distributors being the first to experience industry shifts and spikes, Pitman’s fate can be seen as the canary in the mineshaft for large potions of the industry. Pitman had recently made an unprecedented acquisition of the Charrette company, the largest distributor of wide format inkjet printing technology, the most notable technology at the show. And Pitman announced a controversial agreement to sell EFI-owned Vutek inkjet printing systems, charting an independent inkjet strategy in the face of its major graphic arts consumables vendors, Kodak and Dupont. Such a move by a major distributor is a mile marker in the life cycle of wide format printing technology. Pitman buys little advertising in comparison with major manufacturers and that fact was starkly reflected in the sparse attendance at its press meeting by industry journalists. The advertising-related attendance and the silence that falls at the question period at the end of most press conferences raise the question of the relevance of these programs. Why call them “press” conferences? Perhaps the agendas should read, “Advertiser Update, Room 401, Refreshments Served”? Or “Publishers’ Meeting, Sponsored by: (fill in the large advertiser here). Text of Future Articles Provided/Attendance Mandatory!” Ritual Rumors While millions are spent on imaginative displays, signage and sales staffs to attract show visitors, an insidious counter force that spends nothing at all can gain equal attention and undo a year of carefully planned marketing. This is the annual ritual of rumor mongering. The 2006 Graph Expo was no exception. The rumors are seldom accurate but usually do contain a grain of truth. Often they are manipulated much like political propaganda or smear campaigns by those who might benefit from people believing the rumor. This year’s main rumor was that AGFA was to be acquired, presumably by Heidelberg. Since Heidelberg does sell some Agfa consumable supplies and could possibly expand that relationship, the rumor was said to have substance. Chief among those who enthusiastically spread the prognosis, reportedly, were Kodak sales reps who whispered to dealers who then faithfully passed them on to customers and other vendors. Seldom are rumors positive. They are always cast as disaster watches. This year’s version, for example, was not told as a great expansion of Heidelberg but a bad break for AGFA, its customers and dealers. But not to worry, other vendors were there to help out. The rumor mongering is never in writing. Often the rumors never even show up in news articles. Rumor mongering uses communication channels that are not categorized or measured. Yet, this unfunded and unrecorded information carries enormous costs. It sabotages the promotions of the target of the rumor. Agfa dealers, for example, reported that they were actively searching for back up products in the event the rumor were true. Customers begin to think of alternative providers, just in case. AGFA officials had to spend unproductive time refuting or explaining away the rumor. Part of the success of rumors, despite their inaccuracy or outright fabrication, is that those who are their subjects cannot effectively account for themselves. The sad fact is that perfectly honest people will look you right in the eye and lie about an impending acquisition, merger or sell off. Under penalty of jail, they cannot divulge information that could affect stock pricing and be constructed as insider trading. So they must lie, as tactfully as they can, if confronted directly. Denials, therefore, fuel a rumor as much as real or construed evidence. A relevant response to ritual rumor mongering would be a real press conference in which all parties affected by a rumor could answer the insidious charges and clarify reality. For sure, this press conference would be well attended even without coffee and pastries served. But, then who would believe the speakers? Unseen Force As noted in the first part of this essay, print buyers – the new end-users – are not walking the floor of the show. The trade show ritual calls only for vendors and print providers to attend. Yet, print buyers are at least being talked about in seminars and speeches. And the need for more dialogue – perhaps even a new kind of show – that enables print providers to engage print buyers is recognized. Another force, however, that is behind the new efforts to “drive demand” for print is present at the show, but invisible. It is hovers above the show floor, pulling strings, uplifting some companies, driving others into oblivion. This is the financial community, Wall Street. Rapid growth by the printing industry’s suppliers is now a requirement, not of their printer customers, but investment bankers. Patient, gradual development is inadequate. Large companies are not allowed to languish in mature or stable markets. Wall Street now abandons mature markets so rapidly that companies are forced into innovation whether the market asks for it or not. The investment bankers’ needs and demands, not the customers’, shape graphic arts corporate strategies. Kodak’s MarketMover program, which is designed to stimulate digital print output, may have less to do with new technology or communication trends than cold hearted finance. Capital’s demands were not always so insistent. Mandates on print for higher volume and greater return on investment ramped up in recent decades. Capital is now indifferent to slow and steady business growth but obsessed with blue sky and futuristic enterprises. It demanded that the print industry shift to digital imaging technologies as soon as possible and withdrew funds from those that hesitated. Now, it demands that these technologies increase output rapidly, whether the market needs it or not. Capital’s irrational demand today that the print industry “ramp up” digital volume is eerily reminiscent of the late 90s when capital went mad for dot-com startups while starving out stable and traditional graphic art suppliers. The dot-coms promised innovation, often falsely, and had glorious stories of creating and opening “unlimited” marketers. The traditional companies, meanwhile, were burdened with inconvenient assets, financial statements, customer bases, competitors and well defined markets. Rationality fled the field and hucksterism replaced salesmanship. No wonder the sales ritual at Graph Expo seemed stressed and strangely disconnected from market realities. Whose job is secure? Who is not a candidate for acquisition? Whose funding is running out? Whose stock is stable? The men in blue, pin stripe suits, yellow power ties and wide suspenders were not glad handing on the show floor. They were unseen, but watching.

Commentary & Analysis

FREE: Rituals and Realities at Graph Expo Part 2

By Steve Aranoff &

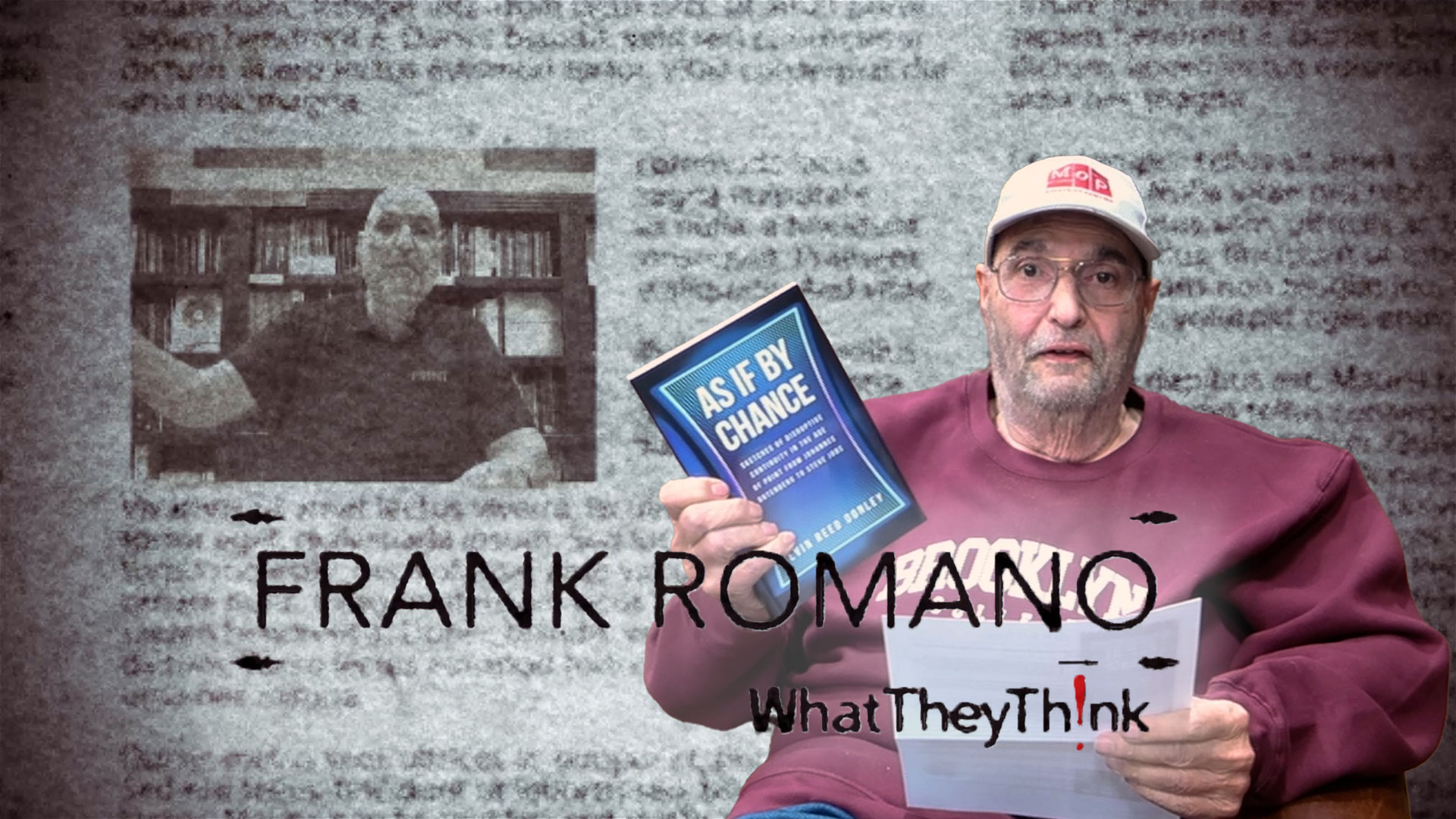

About WhatTheyThink

WhatTheyThink is the global printing industry's go-to information source with both print and digital offerings, including WhatTheyThink.com, WhatTheyThink Email Newsletters, and the WhatTheyThink magazine. Our mission is to inform, educate, and inspire the industry. We provide cogent news and analysis about trends, technologies, operations, and events in all the markets that comprise today's printing and sign industries including commercial, in-plant, mailing, finishing, sign, display, textile, industrial, finishing, labels, packaging, marketing technology, software and workflow.

- 2024 Inkjet Shopping Guide for Folding Carton Presses

- The Future of AI In Packaging

- Inkjet Integrator Profiles: DJM

- Spring Inkjet Update – Webinar

- Security Ink Technologies for Anti-Counterfeiting Measures

- Komori unveils B2 UV Inkjet

- Keeping Nozzles Fresh with Flow

- Komori to Unveil the J-throne 29 Next Generation Digital Press at drupa 2024

WhatTheyThink is the official show daily media partner of drupa 2024. More info about drupa programs

© 2024 WhatTheyThink. All Rights Reserved.