I’m starting a new series called “Faces of Finishing” to share unique insights from individuals in the print finishing industry. There are some really knowledgeable people in this category, but, in general, we’re a low profile group that is not used to getting (or seeking) much attention. So, my goal is to bring some of these faces to the foreground so that we can all benefit from their perspective. I decided to kick-off the series by coaxing my mentor out of retirement for an interview.

Werner Rebsamen

Werner Rebsamen is a bookbinding expert, Professor Emeritus at RIT, and also a great friend of mine. With all of the new advancements and industry focus on finishing, I wanted to know where he sees the greatest change, challenge and opportunity. Werner never disappoints.

Trish Witkowski: With 65+ years of experience in the bookbinding trade, you’ve seen tremendous change in print finishing across the decades of your successful career. What change has surprised you the most?

Werner Rebsamen: In a 1981 Publishers Weekly article, long before Xerox introduced its first DocuTech, I predicted the trend toward short-run printing and binding. That did not go over well with machinery manufacturers producing ever faster and more complex print-finishing systems. Frank Romano's and my forecasts, producing “One Book at a Time,” is now a reality.

Digital printing generated entirely new industries—the most common being the photo book. Some trade and library binders acquired digital printing equipment and offer their clients ultra short run products. Religious publishers and book manufacturers now can print editions in 100+ different languages without stopping their machinery. Machinery manufacturers have adapted to these challenges, using bar-code technologies to match components—like the right case to the right book block. The technology is simply amazing!

TW: What area of the bindery would you like to see more focus on? In your opinion, what is the most overlooked opportunity?

WR: Times have changed. In the past, all major investments in a printing environment were made in the pre-press areas. Recent publications have emphasized that now major investments are being made in print finishing.

It used to take an hour or longer for a changeover of a bindery line. With modern equipment, touch screen technologies, and servo-motors, change overs can be made in no time. This is important, because it takes much longer to remove and move materials to be processed into the print-finishing areas. Those with outdated equipment will struggle to remain competitive.

For example, take a 320-page perfect-bound book set up in 16-page signatures. When a job is finished, the remaining material for the job that was processed must be removed, taken out of the hopper feeding stations, and placed onto the pallets. When everything is taken away, the next job to be processed must be moved into place and loaded into the hopper feeders. That means you must move 20 pallets into place, then place the material into the gathering machines. This issue is the same for saddle stitching lines. Those are time-consuming, labor intensive and expensive tasks.

Newer equipment allows for much quicker fine-tuning and better productivity. But the fact of material handling and the times needed is something no machinery supplier wants to talk about.

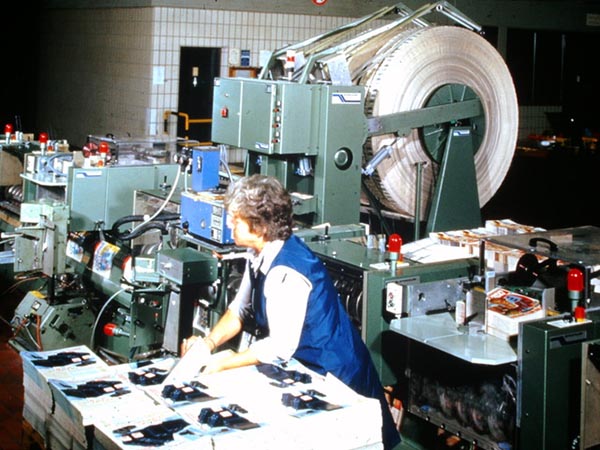

Pallets of gathered material waiting for removal on an adhesive bindery line.

TW: What is the greatest challenge in bookbinding today, and how would you approach solving it?

WR: The word is education—finding and training people. Some of the operators do not even speak English, which further complicates the issue. Today’s operators need to have computer skills and must possess a mechanical aptitude, and that’s challenging to find these days.

As for the incoming material to be converted into printed, marketable items, printers need to familiarize themselves with the importance of material handling. In a RIT graduate study, we found that 76% of all the unwanted stops on saddle stitchers were caused with poorly handled signatures. Fluffy signatures on top of the pallet are full of air, and the ones on the bottom are compressed. Of course curling of signatures becomes a serious issue as well. With uniform, well pressed materials, there is no reason for a machine to stop. That is why in the 1970s, I introduced the slogan: “Well pressed is half bound!"

Example of poor material handling coming to the bindery from the printer.

PrintRoll Technology used in conjunction with manual loading (Image credit: Muller Martini).

I have published several articles on material handling and given many speeches and workshops on this particular issue. At a BIA meeting in San Francisco a few years back, none of the trade binders had any idea what poor material handling actually costs them. The industry has tried PrintRoll and other means to overcome the handicap of material handling with limited success. The best approach is still bundling and overhead cranes for well pressed, uniform materials.

An example of a good handling technique for stacked and uniform materials coming into the print finishing area.

Well-pressed signatures being moved by crane onto the hopper feeder stations. With uniform materials fed into high speed print-finishing systems, they will run virtually non-stop.

Thanks, Werner, for your perspective—and for your immense contribution to this industry.

Could you be the next “Faces of Finishing” interview?

If you have something to say, or a specialized expertise in the print finishing category, I’d like to talk to you. Please send information about what you’d like to share to [email protected].

Discussion

By Jeff White on Mar 01, 2018

Great interview. Werner was one of my favorite instructors at RIT and I still have some of the books I bound in his class back in 78.

By Thomas Lickert on Mar 01, 2018

Nice way to kick-start your "Faces to Finishing". Look forward to more. Lot's of important insights here. It's not the first time I've heard that one trained operators can help you lower overall operating costs. Simprint re-manufacturers pre/post processing products and has done hundreds of installs. There remains a lot of different ideas on how to configure lines in production area's as you know.

What a great mentor you had. Thanks for sharing.

By Mark Pomerantz on Mar 02, 2018

The term 'industry legend' is not one to be tossed around lightly. But in this case, it truly fits. Trish - thank you for honoring Werner Rebsamen, also my professor of Bindery & Finishing, as it was known in those days when I attended RIT. Nobody was more knowledgeable and entertaining at the same time. Reading his perspective today was priceless. Thank you Professor Rebsamen!

By Frank Cost on Mar 03, 2018

Werner,

I knew you couldn't stay retired for long! Wonderful to see you and hear your insights about the industry! You were my teacher, and Trish was my student! So exciting!

Discussion

Join the discussion Sign In or Become a Member, doing so is simple and free