The Museum of Printing doesn’t address the entire history of graphic communications—just the most transformative part of it.

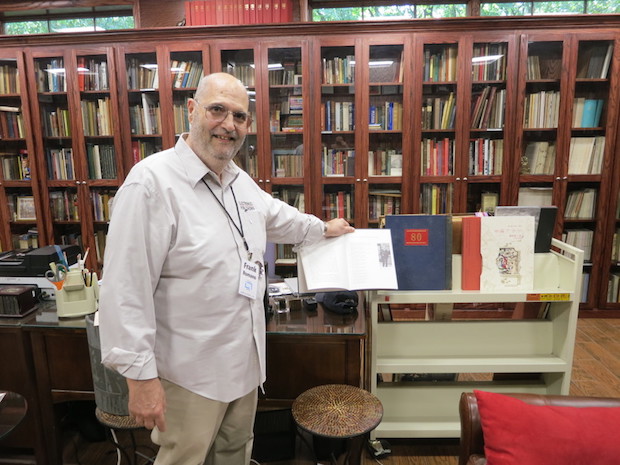

The achievement for which Frank Romano may be best remembered opened its doors in a new location in Haverhill, MA, on September 10. One week later, the museum was the site of a festive reunion by the Typographers Association of New York (TANY) in honor of John Trieste, the trade group’s longtime executive director.

It was appropriate for the unassuming but exhibit-packed building to host a group of people who had witnessed the start of a revolution in typography and prepress when the processes began to change from what they had been to what few had imagined they could be. This is what the Museum of Printing mainly chronicles and celebrates with its unparalleled collection of machines and related artifacts: printing’s dramatic breakthrough into the realm of digitized manufacturing after hundreds of years of analog status quo.

The holdings on display—52 tons of equipment and more than 6,000 books amassed by Romano, co-founders Kim Pickard, Norm Hansen, and Bob Richter, and other supporters of the museum over nearly 30 years—are engagingly curated in a series of themed galleries and a pair of extremely well stocked libraries.

The machine rooms guide visitors along a timeline from roughly the end of the Civil War, with the focus on hot-metal composition and letterpress printing, to a period from the 1950s to the 1980s that spanned the phototype era and the birth of desktop publishing. Composing typewriters, gallery cameras, platemakers, proofing presses, and many other specimens of graphic innovation fill in the details of printing’s progress to a stage where, abruptly, almost everything about it would change forever.

The sense of living history that the collection imparts is overwhelming. Many of the pieces in the fleet of 49 antique letterpresses look as though they could be put back to work printing flyers and handbills as they did two centuries ago. There are massive contraptions such as the Hoe & Co. Rotary Flatbed Newspaper Press, circa 1846, that dominates one of the spaces. Other devices are small in size but huge in significance: for example, the 1980s-vintage Apple Macintosh microcomputers that spelled the beginning of the end for composition and layout as processes for dedicated equipment and specially trained operators only.

Because there is so much to see, it’s not easy to convey just how comprehensive the exhibits are. Romano says, for example, that the Museum of Printing houses the world’s only collection of phototypesetting systems. It has a total of 10 of them, each one helping to tell the story of film-based typography’s brief reign between the end of hot-metal typesetting and the dawn of desktop publishing. That saga begins with the Intertype Fotosetter, a hybrid of a hot-metal linecaster (minus the hot-metal components) and an exposure unit for film characters. The machine is one of just three of its kind remaining in the world.

Touring the galleries, students of printing history will encounter many other devices that truly deserve to be called iconic. There is, of course, Ottmar Mergenthaler’s Linotype—the world’s first successful mechanized linecasting system. The museum has five of them, including a model that could run on punched paper tape from a teletypesetter.

Prepress veterans will recognize the imposing bulk of the Hell Chromagraph DC 300 Drum Color Scanner, a machine that saw 2,500 installations at the then-as-now astonishing price of almost $1 million each. Not far away is the Linotronic 300 film imagesetter, one of a quartet of solutions that turned the desktop publishing revolution of the mid-1980s into an industry-changing coup (the others were the WYSYWIG Apple computing platform, the PostScript page description language, and Aldus PageMaker page composition software).

And everywhere throughout the museum, there is type: thousands upon thousands of wooden and metal letterforms in job case drawers, press chases, and wall-mounted displays. This treasure trove includes 1,700 cases of foundry type and two and a quarter tons of new foundry type in their original wrappers. Visitors can buy sets of these fonts, wrapped like candy bars but weighing much more, in the museum’s gift shop.

The museum is not only a premier exhibit space for the artifacts of printing. Incorporating two commemorative libraries, it is an equally important resource for printing research and scholarship.

Standing sentry at the entrance of the larger of the two repositories, the Romano Book Arts Library, is a tall bronze relief of Charles Francis (1848-1936), founder and first president of the Printers League of New York City and the Printers League of America. Casebound books and ephemera, some of them quite rare, from before and after Francis’s time fill the room’s 32 mahogany bookcases from floor to ceiling. In the center of the library, faces of bygone industry members gaze from a pillar shingled with their portraits on cuts—photoengraved relief plates made for letterpress printing.

Romano, who has spent most of his life collecting (as well as writing) books about printing, has also acquired complete sets of the industry’s seminal trade periodicals—Inland Printer, New England Printer, and the original weekly Printing News—in bound volumes. Another gem of the library, its vast archive of font artwork from the Mergenthaler Linotype Company, is being scanned and digitized in a project with Stanford University.

John Trieste, the TANY honoree, had the pleasure of seeing his name over the doorway of a room now known as the John Trieste Memorial Type Library. The space will serve as a typographic reference center with type specimen books, publications about typography, and other essential materials.

An institution as rich and complex as the Museum of Printing does not come into being overnight, nor does it exist for as long as this one has without enduring its share of growing pains. As Romano tells the story, the museum appears finally to have reached a point where its location is permanent and the collection has the room it needs to be displayed as it deserves.

His connection with the museum started in 1978 when, as the editor of New England Printer, he wrote a piece about the installation of a phototypesetting system at the Boston Globe. The newspaper’s management agreed that the outgoing hot-metal equipment had historical value and that it ought to be preserved someplace where people could see it.

The Taylor family, who were the owners of the Boston Globe at the time, liked the idea and found space in a former mill building in Lowell, MA, that became the museum’s first home. The collection grew under Romano’s general supervision until word came that the mill was to be converted into condominiums. This forced a move to a different space in Lawrence, MA, where eventually, the same thing happened—relocation due to condo conversion.

t was now 1999, and the museum was operating out of its third address in North Andover, MA. It would remain in this venue, which Romano describes as having been “very limited,” until last year, when a more spacious building that previously had housed an electrical supply business became available in Haverhill. Refurbishing and move-in proceeded until the official opening on September 10.

The Museum of Printing is open to the public on Saturday from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. Incorporated since 1978 as The Friends of the Museum of Printing, Inc., a not-for-profit organization, it depends on modest admission fees, gift store sales, memberships, and donations for 100% of its revenue. Running the museum is purely a labor of love. “It only exists because of the volunteers,” Romano says.

Money from the kinds of grants that support exhibition spaces has been hard to come by because, as Romano observes, “nobody wants to stare at an old machine” in the setting of an industrial museum any more. In fact, the Museum of Printing owns more historic iron than it has room to show in Haverhill—the rest of its holdings are stored in a warehouse in Chelsea, MA, a city across the Mystic River from Boston.

But, Romano emphasizes that the Museum of Printing doesn’t acquire vintage graphic equipment just for the sake of stockpiling it. The goal, rather, is to select and present exemplars of the technologies whose stories the museum is attempting to tell. Another objective is to position the museum as a cultural center by promoting its works of graphic art and its library resources.

To attract local attention, the museum stayed open for a week with no admission charges following the opening on September 10. The Haverhill Eagle-Tribune profiled it, and during the TANY event, a representative of the area’s Chamber of Commerce said the group would include the museum on its must-see list of cultural and historical attractions in the region.

Now, support of the museum is up to the industry that inspired its creation. Located less than 40 miles north of Boston, it is easy to reach from anywhere in the Northeast and well worth the journey for those coming from farther away. (Options for visiting printing museums in the U.S. are limited: the only other ones to see are in Carson, CA, and Houston, TX).

Romano says that the Museum of Printing will be of interest and value to “anyone who wants to understand the history of communications.” That includes the readers of these words and all those to whom they can spread the message about the extraordinary panorama of printing history that is now on display in Haverhill.

Discussion

By Shoshana Burgett on Sep 23, 2016

Gillian and I can't wait to see the new facility.

By Deanna Gentile on Sep 23, 2016

Congrats Frank for achieving this....

By Eric Vessels on Sep 26, 2016

Got a walk-through when it was unfinished. Can't wait to see it all put together!

By Donald Goldman on Oct 03, 2016

Hi,

Thanks Patrick for the great introduction to the Museum. And thanks Frank for your constant industry support and legacies through the years.

Sorry to miss the open house but will be visiting with an artist and publisher friend next Saturday.

Don Goldman

Discussion

Join the discussion Sign In or Become a Member, doing so is simple and free