Commentary & Analysis

US Commercial Printing Shipments per Employee in Sideways Trend: The Rest is Not So Obvious

If you looked at the shipments per employee data for the commercial printing industry over time,

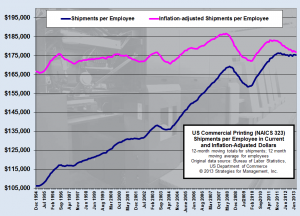

If you looked at the shipments per employee data for the commercial printing industry over time, you'd be convinced of a history of productivity improvement that must be making everyone wealthy beyond their dreams. Since 1994, using manufacturing shipments data from the Commerce Department and employee data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, each employee has added $70,000 of shipments value to their job. (click chart to enlarge)

It's purchasing power that matters, and in that approximate 20 year span, it's up $10,000, not $70,000, or about $500 per year. The rest is inflation.

The number is in the range of $177,000 per employee, and it recently peaked in Spring 2011 at about $183,000. In 2008, it was as high as $186,000. These vary by segment, but those data are not available in a monthly format that allows continuous analysis. Commercial offset is in the range of $225,000 per employee, while pre- and post-press businesses average about $140,000. Data about all 12 NAICS segments as defined by the Commerce Department are not available consistently.

There are some curious lessons that can be gained in reviewing these data. First, no matter how the industry and media dynamics change, we end up in roughly the same spot over time, as if we keep returning to an uncomfortable equilibrium no matter what we tried. Second, even keeping up at this level might be considered heroic, with the downward pressure on shipments caused by media alternatives and other factors. Third, shipments per employee have remained at these levels even though the job count had dropped by more than 300,000 jobs over the last decade and a half. Fourth, this approximate level of shipments has been maintained when the industry had significant profits (late 1990s) and when it has not (the last decade). Fourth, technology changes, such as the growing share of digital printing, has done little to make a dent in the long-term trend. Fifth, the shift in emphasis from print to marketing services has not had significant effect. Sixth, these data do not track well with capacity utilization data; throughout the period of this chart, capacity utilization as measured by the Federal Reserve was on a 30+ year downward trend.

After a while, you can convince yourself that nothing matters, that the equilibrium are is supermagnetic, and when it looks like shipments per employee is breaking away from the trend, it starts to head back.

That's not the case. My usual admonition applies: these are total industry data, including companies doing well and companies that are not. The average team record in the NFL is .500, or the same number of wins as there are losses. Yet some companies excel when others fail, some excel for a season or two, and some seem to excel for long periods of time while others are mired in problems for generations. Business is not sports, the industry is not breakeven. Our history is that the profit-making companies outnumber the "treading water" companies by 3 to 1. We know from PIA financial ratio leaders that profit leaders, in rough terms, have the same basic costs as other printers, but higher sales per employee rates. We know that in recessionary periods, well run companies have shrinking profits but the gap between the profit leaders and the others widens during those periods even though their profits are lower. They do not do one major thing better than the others, they do lots of things a little better than the others, and those small positive differences accumulate at the bottom line.

There is no one measure that should be used for an industry and an individual business. This one, shipments per employee, can be used by both, but should not be used in the same way. For an industry, it shows the importance of factoring out distortions of inflation to see long term trends. For a company, this has to be viewed in terms of the costs and resource decisions that are appropriate for that one company, and no other. What each company does with each dollar can be, and should be, quite different.

# # #

About Dr. Joe Webb

Dr. Joe Webb is one of the graphic arts industry's best-known consultants, forecasters, and commentators. He is the director of WhatTheyThink's Economics and Research Center.

Video Center

- Questions to ask about inkjet for corrugated packaging

- Can Chinese OEMs challenge Western manufacturers?

- The #1 Question When Selling Inkjet

- Integrator perspective on Konica Minolta printheads

- Surfing the Waves of Inkjet

- Kyocera Nixka talks inkjet integration trends

- B2B Customer Tours

- Keeping Inkjet Tickled Pink

© 2024 WhatTheyThink. All Rights Reserved.