Commentary & Analysis

Statistical Trends in Print, or, Dr. Joe's Mixed Media Message

The trends in commercial printing demand are often up to debate,

The trends in commercial printing demand are often up to debate, but sometimes statistical analysis can be helpful in understanding them better. Economic events are often the reasons given for shifts in demand and shipments, but that's much to nebulous. We know there are more specific issues, and there is too much general evidence that strong economic growth only makes the adoption rate of digital technologies and media stronger.

In some recent analysis, the regression model of real GDP and CPI-adjusted printing shipments shows that for every billion dollar increase in real GDP results in a -$19.4 million change in commercial print shipments. This regression equation has r²= 71.9%, which is a strong statistical relationship, no matter how unsatisfying (or confusing) the thought is that a growing economy might actually hurt an industry rather than benefit it.

Now is a good time to make the point that statistical relationships change over time. There was a time when this relationship between print and the economy was positive. Also, depending on the starting year of the data series, you can create different results. I can't get a positive result to appear unless I ignore the last decade or more. But I can make the r² change and the dollar relationship to GDP change. The bigger problem with statistical data is that models can only detect change after the change has occurred and been evident for a while. It is a warning sign to managers when models don't reflect reality any longer. When the models say one thing and reality says something else, that's not a problem with the model, it's a problem with management clinging to a model rather than relying on their experience and ability to interpret what they see and experience first hand. Models are intended to help us see new things or to give order to things that seem disordered. Models that don't work tell us as much or sometime more than models that do. (Statistical soapbox time is now finished).

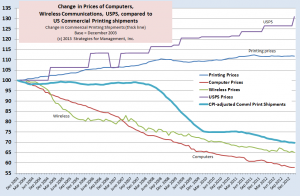

There are other factors that affect demand, notably the prices of other goods, notably computer equipment, wireless communications, and the costs of postage. We compared these data series with printing shipments. The Producer Price Index for computer equipment has an r²=76.9%, and it means that every 1-point positive change in the index equals $337 million more print sales. The only problem is that the PPI for computing equipment keeps going down, so every 1-point negative change is a $337 million decline in print shipments. Since 2000, the PPI for computers has fallen by 58%. If we could just repeal Moore's Law (you know, that computing power doubles every 18 months while the price decreases by half) things would be okay. (click chart to enlarge)

Wireless communications PPI has an r²=65.0%, and every 1-point change equals a $1.1 billion change in shipments, and that has fallen as well. Since December 2003, that index has fallen by 35%.

And now my favorite: the PPI for the postal service. Devoid of recognition of the market prices of computers and communications, the PPI for the USPS as increased 43.7% since January 2000. Every 1-point upward change in its PPI is equivalent to a decrease in printing shipments by $912 million. The r² for that? 91.6%; a stronger statistical relationship than commercial print's relationship with the prices for computing technology and wireless communications, and GDP. Since December 2003, Commercial printing prices are up +11.8%. Much of that rise has been in materials and operations costs, with little, if any going to the printing businesses themselves. The USPS often touts that its prices are only rising at the rate of inflation. For first class, that is the case, but for other classes, it is not; many bulk classes have changed outside the CPI boundary.

It was not always this way. When there were limited substitutes, most postal increases were absorbed by users and paid for by more efficient mailing practices, such as cleaner mailing lists, changes in sizes of materials mailed or the weight of the papers used, or implementing new ways of increasing response rates (decades ago, use of toll-free phone numbers did just that). There was a time when postal increases were whined about but not much happened to aggregate volume. That's obviously not the case any more.

But there's a deeper fallacy in the USPS contention that postal increases are essentially limited to inflation. They have direct competitors that are falling in price, not rising. This means that every time the USPS raises prices, even following the CPI, the gap between their competitive replacements widens. That widening gap creates pressure elsewhere in the value chain of postal-distributed media.

When elephants fight, as the saying goes, the biggest losers are the ants.

When print is budgeted by a client, they budget their total costs, and judge the value of the effort against the total cost of other media. In that print job price, they include the distribution cost of that printed good. In a market with declining demand, prices are supposed to adjust downward in an attempt to match the capability to produce with the new demand level. USPS prices should have been going down in a normal market, but they obviously have not, because postal prices are not subject to market pricing. Because of that, printing prices have stagnated, but printing prices should have been being reduced as well.

Print prices are lower now than ever, practically, because they have not kept up with inflation. Even that is not enough, because they needed to decline in some commensurate manner with competitive substitutes. Because pricing could not adjust to the shift in demand, the nature of supply changed. This resulted in the closure of print businesses and the departure of more than about 350,000 workers from the industry in the last 15 years.

This is the nature of creative destruction, of how new goods replace old goods by changing the relationship of their resources and their costs in response to competitors considered to be outside of the industry.

What is a printer to do? This is where the creativity and innovative approach of our entrepreneurs is found, or should be. Remember that person with the media budget? Focus on their target audience and make all of their media budget more effective. Postal costs are only part of the problem. It's what you do with those costs and how you leverage them that's important. We know that postal costs are not market-relevant to the new media choices available today, and that will not be changing. When the cost of something rises, it becomes an incentive to use that cost more wisely and judiciously.

Make sure that postal-distributed media perform functions that other media cannot do, and use postal-based formats to make other media more effective. That requires a high degree of wisdom about client operations, objectives, and long-term goals, and necessitates a different way of selling and marketing our industry's capabilities.

It also means that non-postal print becomes a more important good in the future success of the print business. This is why specialty goods, posters, signage, promotional items, personalized goods, all have more positive market futures, especially when they tie-in with digital media (such as QR codes on posters, and tie-ins with local media like Foursquare and others).

In an overcommunicated society, media mix, even for small businesses, is critical. It's hard to justify one communications channel when no one can anticipate which channel a customer or prospect will use. The store that relied on its Yellow Pages ad now relies on a poster in its window, a website, a Facebook page, and a graphic-wrapped delivery truck. It moved from relying on one medium, to relying on many. This means that branding and consistency across all media is essential, and that being able to produce shorter runs of hard goods, like print, posters, and other items, is a constant requirement.

Short run jobs, as always, place pressure on the nature of capital investment and fixed costs of print businesses. It's easy to build a business when there is a steady flow of jobs of $5,000 or more. It's harder to build a business with an erratic flow of $100 jobs without a significant change in strategy that affects the entire business.

# # #

About Dr. Joe Webb

Dr. Joe Webb is one of the graphic arts industry's best-known consultants, forecasters, and commentators. He is the director of WhatTheyThink's Economics and Research Center.

Video Center

- Questions to ask about inkjet for corrugated packaging

- Can Chinese OEMs challenge Western manufacturers?

- The #1 Question When Selling Inkjet

- Integrator perspective on Konica Minolta printheads

- Surfing the Waves of Inkjet

- Kyocera Nixka talks inkjet integration trends

- B2B Customer Tours

- Keeping Inkjet Tickled Pink

© 2024 WhatTheyThink. All Rights Reserved.