As we have written about the changes in the seasonality of the commercial printing business over time, March has become the biggest month of the printing year. (For a discussion of the change in seasonality, please see the column about it). We will have a first indication of March's volume with the release of printing employment data on Friday, April 6. Based on last year, we would expect a shipments level of in the range of $7.4 billion.

One of our readers who accessed the Commerce data for February directly recently asked if the month's data should be adjusted for the extra selling day of leap year. It's kind of a fool's errand to torture that kind of precision out of these kinds of data. First, the data are always subject to revision. Every month's release of new data includes a revision of the prior month's data, as noted above. Second, every May, the Commerce Department makes a major revision to the entire data series going back five years, with the three most years subject to some significant revisions. There have been cases where data are revised up from the original report, then revised below the original estimate, and then revised yet again. Third, one can't always assume that February is a short month; depending on the way holidays and weekends fall for a particular month, what seems like a short month may not be. When I counted the days, February 2012 had 21 business days, while January had 20, despite being two days longer. Fourth, we can't always assume that the days in the workweek are common throughout the year. In July, for example, many companies shut down for two weeks for maintenance and vacations. Some companies, especially larger ones, run production six or seven days a week. Then, of course, there are differences in numbers of shifts. With so many variables, it's hard enough to keep things straight, but one thing you don't want to do is to impart a false level of precision to data that are not collected with precision.

As managers, we need to know that data can be revised and don't always reflect what we may believe at first glance. Data that are estimates, and only become reliable years later, long after business decisions were made with them. We must make decisions as best we can with what we have, synthesizing data and also first hand experiences of ourselves and others. Macroeconomic data, like GDP, are of little use in these situations other than to provide some very general background. Technology trends are far more powerful. One only needs to be reminded of Apple computer, now selling iPads at the rate of 4 million per month, and iPhones at the rate of 12 million per month.

# # #

As we have written about the changes in the seasonality of the commercial printing business over time, March has become the biggest month of the printing year. (For a discussion of the change in seasonality, please see the column about it). We will have a first indication of March's volume with the release of printing employment data on Friday, April 6. Based on last year, we would expect a shipments level of in the range of $7.4 billion.

One of our readers who accessed the Commerce data for February directly recently asked if the month's data should be adjusted for the extra selling day of leap year. It's kind of a fool's errand to torture that kind of precision out of these kinds of data. First, the data are always subject to revision. Every month's release of new data includes a revision of the prior month's data, as noted above. Second, every May, the Commerce Department makes a major revision to the entire data series going back five years, with the three most years subject to some significant revisions. There have been cases where data are revised up from the original report, then revised below the original estimate, and then revised yet again. Third, one can't always assume that February is a short month; depending on the way holidays and weekends fall for a particular month, what seems like a short month may not be. When I counted the days, February 2012 had 21 business days, while January had 20, despite being two days longer. Fourth, we can't always assume that the days in the workweek are common throughout the year. In July, for example, many companies shut down for two weeks for maintenance and vacations. Some companies, especially larger ones, run production six or seven days a week. Then, of course, there are differences in numbers of shifts. With so many variables, it's hard enough to keep things straight, but one thing you don't want to do is to impart a false level of precision to data that are not collected with precision.

As managers, we need to know that data can be revised and don't always reflect what we may believe at first glance. Data that are estimates, and only become reliable years later, long after business decisions were made with them. We must make decisions as best we can with what we have, synthesizing data and also first hand experiences of ourselves and others. Macroeconomic data, like GDP, are of little use in these situations other than to provide some very general background. Technology trends are far more powerful. One only needs to be reminded of Apple computer, now selling iPads at the rate of 4 million per month, and iPhones at the rate of 12 million per month.

# # #

Commentary & Analysis

February US Commercial Printing Shipments Flat with 2011

February 2012 printing shipments were reported by the Commerce Department as flat with 2011,

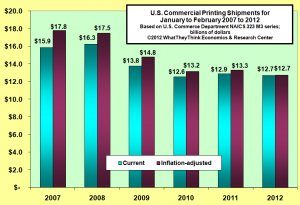

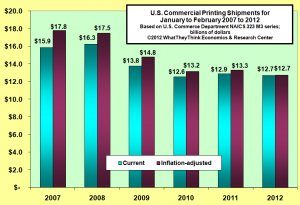

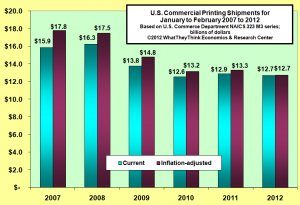

February 2012 printing shipments were reported by the Commerce Department as flat with 2011, at $6.358 billion in current US dollars. The was the same amount as January 2012 after a -$43 million downward revision. (It looked so odd that the January and February 2012, and February 2011 were exactly the same that we called the Commerce Department, and they confirmed that the reporting was correct).

On an inflation-adjusted basis, February shipments were down -2.8%. For the first two months of the year, shipments are down -$203 million, or -1.6%, and down -$579 million, or -4.3%. (click on chart to enlarge)

As we have written about the changes in the seasonality of the commercial printing business over time, March has become the biggest month of the printing year. (For a discussion of the change in seasonality, please see the column about it). We will have a first indication of March's volume with the release of printing employment data on Friday, April 6. Based on last year, we would expect a shipments level of in the range of $7.4 billion.

One of our readers who accessed the Commerce data for February directly recently asked if the month's data should be adjusted for the extra selling day of leap year. It's kind of a fool's errand to torture that kind of precision out of these kinds of data. First, the data are always subject to revision. Every month's release of new data includes a revision of the prior month's data, as noted above. Second, every May, the Commerce Department makes a major revision to the entire data series going back five years, with the three most years subject to some significant revisions. There have been cases where data are revised up from the original report, then revised below the original estimate, and then revised yet again. Third, one can't always assume that February is a short month; depending on the way holidays and weekends fall for a particular month, what seems like a short month may not be. When I counted the days, February 2012 had 21 business days, while January had 20, despite being two days longer. Fourth, we can't always assume that the days in the workweek are common throughout the year. In July, for example, many companies shut down for two weeks for maintenance and vacations. Some companies, especially larger ones, run production six or seven days a week. Then, of course, there are differences in numbers of shifts. With so many variables, it's hard enough to keep things straight, but one thing you don't want to do is to impart a false level of precision to data that are not collected with precision.

As managers, we need to know that data can be revised and don't always reflect what we may believe at first glance. Data that are estimates, and only become reliable years later, long after business decisions were made with them. We must make decisions as best we can with what we have, synthesizing data and also first hand experiences of ourselves and others. Macroeconomic data, like GDP, are of little use in these situations other than to provide some very general background. Technology trends are far more powerful. One only needs to be reminded of Apple computer, now selling iPads at the rate of 4 million per month, and iPhones at the rate of 12 million per month.

# # #

As we have written about the changes in the seasonality of the commercial printing business over time, March has become the biggest month of the printing year. (For a discussion of the change in seasonality, please see the column about it). We will have a first indication of March's volume with the release of printing employment data on Friday, April 6. Based on last year, we would expect a shipments level of in the range of $7.4 billion.

One of our readers who accessed the Commerce data for February directly recently asked if the month's data should be adjusted for the extra selling day of leap year. It's kind of a fool's errand to torture that kind of precision out of these kinds of data. First, the data are always subject to revision. Every month's release of new data includes a revision of the prior month's data, as noted above. Second, every May, the Commerce Department makes a major revision to the entire data series going back five years, with the three most years subject to some significant revisions. There have been cases where data are revised up from the original report, then revised below the original estimate, and then revised yet again. Third, one can't always assume that February is a short month; depending on the way holidays and weekends fall for a particular month, what seems like a short month may not be. When I counted the days, February 2012 had 21 business days, while January had 20, despite being two days longer. Fourth, we can't always assume that the days in the workweek are common throughout the year. In July, for example, many companies shut down for two weeks for maintenance and vacations. Some companies, especially larger ones, run production six or seven days a week. Then, of course, there are differences in numbers of shifts. With so many variables, it's hard enough to keep things straight, but one thing you don't want to do is to impart a false level of precision to data that are not collected with precision.

As managers, we need to know that data can be revised and don't always reflect what we may believe at first glance. Data that are estimates, and only become reliable years later, long after business decisions were made with them. We must make decisions as best we can with what we have, synthesizing data and also first hand experiences of ourselves and others. Macroeconomic data, like GDP, are of little use in these situations other than to provide some very general background. Technology trends are far more powerful. One only needs to be reminded of Apple computer, now selling iPads at the rate of 4 million per month, and iPhones at the rate of 12 million per month.

# # #

As we have written about the changes in the seasonality of the commercial printing business over time, March has become the biggest month of the printing year. (For a discussion of the change in seasonality, please see the column about it). We will have a first indication of March's volume with the release of printing employment data on Friday, April 6. Based on last year, we would expect a shipments level of in the range of $7.4 billion.

One of our readers who accessed the Commerce data for February directly recently asked if the month's data should be adjusted for the extra selling day of leap year. It's kind of a fool's errand to torture that kind of precision out of these kinds of data. First, the data are always subject to revision. Every month's release of new data includes a revision of the prior month's data, as noted above. Second, every May, the Commerce Department makes a major revision to the entire data series going back five years, with the three most years subject to some significant revisions. There have been cases where data are revised up from the original report, then revised below the original estimate, and then revised yet again. Third, one can't always assume that February is a short month; depending on the way holidays and weekends fall for a particular month, what seems like a short month may not be. When I counted the days, February 2012 had 21 business days, while January had 20, despite being two days longer. Fourth, we can't always assume that the days in the workweek are common throughout the year. In July, for example, many companies shut down for two weeks for maintenance and vacations. Some companies, especially larger ones, run production six or seven days a week. Then, of course, there are differences in numbers of shifts. With so many variables, it's hard enough to keep things straight, but one thing you don't want to do is to impart a false level of precision to data that are not collected with precision.

As managers, we need to know that data can be revised and don't always reflect what we may believe at first glance. Data that are estimates, and only become reliable years later, long after business decisions were made with them. We must make decisions as best we can with what we have, synthesizing data and also first hand experiences of ourselves and others. Macroeconomic data, like GDP, are of little use in these situations other than to provide some very general background. Technology trends are far more powerful. One only needs to be reminded of Apple computer, now selling iPads at the rate of 4 million per month, and iPhones at the rate of 12 million per month.

# # #

As we have written about the changes in the seasonality of the commercial printing business over time, March has become the biggest month of the printing year. (For a discussion of the change in seasonality, please see the column about it). We will have a first indication of March's volume with the release of printing employment data on Friday, April 6. Based on last year, we would expect a shipments level of in the range of $7.4 billion.

One of our readers who accessed the Commerce data for February directly recently asked if the month's data should be adjusted for the extra selling day of leap year. It's kind of a fool's errand to torture that kind of precision out of these kinds of data. First, the data are always subject to revision. Every month's release of new data includes a revision of the prior month's data, as noted above. Second, every May, the Commerce Department makes a major revision to the entire data series going back five years, with the three most years subject to some significant revisions. There have been cases where data are revised up from the original report, then revised below the original estimate, and then revised yet again. Third, one can't always assume that February is a short month; depending on the way holidays and weekends fall for a particular month, what seems like a short month may not be. When I counted the days, February 2012 had 21 business days, while January had 20, despite being two days longer. Fourth, we can't always assume that the days in the workweek are common throughout the year. In July, for example, many companies shut down for two weeks for maintenance and vacations. Some companies, especially larger ones, run production six or seven days a week. Then, of course, there are differences in numbers of shifts. With so many variables, it's hard enough to keep things straight, but one thing you don't want to do is to impart a false level of precision to data that are not collected with precision.

As managers, we need to know that data can be revised and don't always reflect what we may believe at first glance. Data that are estimates, and only become reliable years later, long after business decisions were made with them. We must make decisions as best we can with what we have, synthesizing data and also first hand experiences of ourselves and others. Macroeconomic data, like GDP, are of little use in these situations other than to provide some very general background. Technology trends are far more powerful. One only needs to be reminded of Apple computer, now selling iPads at the rate of 4 million per month, and iPhones at the rate of 12 million per month.

# # #

About Dr. Joe Webb

Dr. Joe Webb is one of the graphic arts industry's best-known consultants, forecasters, and commentators. He is the director of WhatTheyThink's Economics and Research Center.

Video Center

WhatTheyThink is the official show daily media partner of drupa 2024. More info about drupa programs

© 2024 WhatTheyThink. All Rights Reserved.