While it is true that small business employment is more than half of total employment in the US, the reality is that small business needs large businesses to be healthy, since so many small businesses sell their services to large businesses. What's a large business? While the definition varies a bit by industry, the one that fits most is having 500 or more employees. In the chart above, I used 50 employees as the cutoff, and even when I ignore the microbusinesses, the 50+ group is only 5.6% of total business establishments. Of course, small businesses create more employment, because there are so many of them. But small businesses also lose the most employees.

Small businesses are essential to the economy, but stimulating employment in small businesses alone is not the answer. Stimulating the demand for the services and goods produced by small businesses, often in service to large businesses, is far more important. All big businesses started as small businesses that found a market for what they offered. When that market does not demand goods and services, there will be no increase in small business employment.

Small business is overly burdened by regulatory costs. This is true, and not enough small businesses realize it. While all businesses have regulatory costs, some good, some bad, some seriously detrimental to doing business, the biggest problem is that regulatory costs are so hard to measure. In many ways, it's not that a small business is burdened by regulatory costs that is the problem, it's the cost of starting a new business and taking the first steps that is. The risks of starting a business are bad enough; when you add the costs of regulatory compliance that must be met well before a unit of goods or services is produced, that is a drag on the economy that few recognize. To understand economics, one must have a great appreciation of the unseen, not just the physical manifestations of commerce. No one can see a decision not to do something, and regulations often create vacuums in economic activity. As economist Milton Friedman warned, all regulations are applied to existing businesses, but no one seems to realize the unintended consequences that may affect businesses yet to be started.

It's worth taking a look at some of the regulatory costs of business, and I strongly recommend that all small business owners aggressively remind their legislators, whether local, state, or national, and especially their advocates, such as Chambers of Commerce, about these resources. The Small Business Administration released a report in September 2010 that estimated the costs of regulation as more than $1.7 trillion dollars in 2008. The report is quite an eye-opener; it should be, because that $1.7 trillion was before the recession, and before the new regulations issued in light of the financial collapse and new health care plans. A small manufacturing business pays, according to the government's own data, more that $14,000 per employee, in compliance costs. If anyone questions why manufacturers consider going overseas, show them table 14, page 50 (p54 of the PDF file). The combination of fast-growing markets alone is enough to capture company interests, but combine that with lower compliance costs, and the decision can be quite compelling.

Also take a look at the Competitive Enterprise Institute's Ten Thousand Commandments report for 2011 further discusses the regulatory environment, with one of its key indicators being the number of pages in the Federal Register, where all new regulations and laws are reported. The report states "Regulatory costs now comfortably exceed the cost of individual income taxes, and those costs vastly exceed revenue from corporate taxes... regulatory costs now tower over the estimated 2010 individual income taxes of $936 billion... Corporate

income taxes, estimated at $157 billion, are dwarfed by regulatory costs... regulatory cost levels exceed the level of pretax corporate profits..."

Are small businesses disproportionately affected by regulatory costs? Yes, and those costs divert resources away from productive activities in the same manner that they may prevent hazards or problems that the regulations were created for. But the ultimate costs are that the economy is deprived of more small businesses because the barriers to entry that regulations are inadvertently created. In the end, regulatory costs and business taxes, are all in the prices paid in the marketplace by consumers and other businesses.

While it is true that small business employment is more than half of total employment in the US, the reality is that small business needs large businesses to be healthy, since so many small businesses sell their services to large businesses. What's a large business? While the definition varies a bit by industry, the one that fits most is having 500 or more employees. In the chart above, I used 50 employees as the cutoff, and even when I ignore the microbusinesses, the 50+ group is only 5.6% of total business establishments. Of course, small businesses create more employment, because there are so many of them. But small businesses also lose the most employees.

Small businesses are essential to the economy, but stimulating employment in small businesses alone is not the answer. Stimulating the demand for the services and goods produced by small businesses, often in service to large businesses, is far more important. All big businesses started as small businesses that found a market for what they offered. When that market does not demand goods and services, there will be no increase in small business employment.

Small business is overly burdened by regulatory costs. This is true, and not enough small businesses realize it. While all businesses have regulatory costs, some good, some bad, some seriously detrimental to doing business, the biggest problem is that regulatory costs are so hard to measure. In many ways, it's not that a small business is burdened by regulatory costs that is the problem, it's the cost of starting a new business and taking the first steps that is. The risks of starting a business are bad enough; when you add the costs of regulatory compliance that must be met well before a unit of goods or services is produced, that is a drag on the economy that few recognize. To understand economics, one must have a great appreciation of the unseen, not just the physical manifestations of commerce. No one can see a decision not to do something, and regulations often create vacuums in economic activity. As economist Milton Friedman warned, all regulations are applied to existing businesses, but no one seems to realize the unintended consequences that may affect businesses yet to be started.

It's worth taking a look at some of the regulatory costs of business, and I strongly recommend that all small business owners aggressively remind their legislators, whether local, state, or national, and especially their advocates, such as Chambers of Commerce, about these resources. The Small Business Administration released a report in September 2010 that estimated the costs of regulation as more than $1.7 trillion dollars in 2008. The report is quite an eye-opener; it should be, because that $1.7 trillion was before the recession, and before the new regulations issued in light of the financial collapse and new health care plans. A small manufacturing business pays, according to the government's own data, more that $14,000 per employee, in compliance costs. If anyone questions why manufacturers consider going overseas, show them table 14, page 50 (p54 of the PDF file). The combination of fast-growing markets alone is enough to capture company interests, but combine that with lower compliance costs, and the decision can be quite compelling.

Also take a look at the Competitive Enterprise Institute's Ten Thousand Commandments report for 2011 further discusses the regulatory environment, with one of its key indicators being the number of pages in the Federal Register, where all new regulations and laws are reported. The report states "Regulatory costs now comfortably exceed the cost of individual income taxes, and those costs vastly exceed revenue from corporate taxes... regulatory costs now tower over the estimated 2010 individual income taxes of $936 billion... Corporate

income taxes, estimated at $157 billion, are dwarfed by regulatory costs... regulatory cost levels exceed the level of pretax corporate profits..."

Are small businesses disproportionately affected by regulatory costs? Yes, and those costs divert resources away from productive activities in the same manner that they may prevent hazards or problems that the regulations were created for. But the ultimate costs are that the economy is deprived of more small businesses because the barriers to entry that regulations are inadvertently created. In the end, regulatory costs and business taxes, are all in the prices paid in the marketplace by consumers and other businesses.

Commentary & Analysis

Counterintuitive Economics

This week'

This week's column is a collection of comments and links to a variety of items that might seem counter-intuitive to prevailing thinking found in the economics press. I hope you enjoy them.

All the manufacturing jobs are gone. Not yet, but manufacturing jobs are disappearing worldwide. Economics professor Mark Perry of the University of Michigan explains how manufacturing has a shrinking share of worldwide GDP. The baseline data come from the United Nations. There was an analysis about seven years ago (no longer available online) by investment firm AllianceBernstein that showed even China's manufacturing force was declining. Yet, at the same time, in another Mark Perry post, he explains how the inflation-adjusted output per worker has been rising. The number of workers in a sector is not important. During the 1930s and 1940s, approximately one-quarter of the workforce was involved in agriculture. Today, it is less than 2%, and the USA is a net exporter of agricultural goods. A lot of it has to do with the way workers are classified. A software worker is often classified in the publishing industry, yet what they are doing, creating the packets of instructions that run computers, would have years and years ago been classified as part of manufacturing. When a manufacturing company has a company cafeteria, its cafeteria workers are considered manufacturing employees because they work in a manufacturing company. If the company outsources its cafeteria management to Aramark or Host, suddenly, the number of manufacturing workers declines, and those same workers are now considered service workers. Construction workers are considered to be service workers, not manufacturing workers. If they install a pre-manufactured kitchen cabinet, that cabinet was created by a manufacturing worker. If the construction worker builds a cabinet on site, it was built by a service worker. The common thinking that manufacturing jobs are somehow better than any other job diverts attention from the real business revolutions that are happening every day in communications, transportation, logistics, medical delivery, education, and professional services. Manufacturing will become so automated, manufacturing workers will decline just like agricultural workers did; let's not make the assumption that it is automatically negative. The categorization of workers is not important, but the real incomes of workers is far more important, regardless of how a bureaucratic rule forces them to be counted.

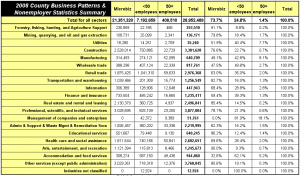

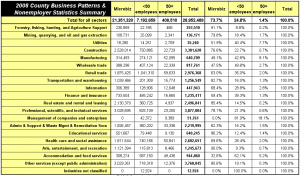

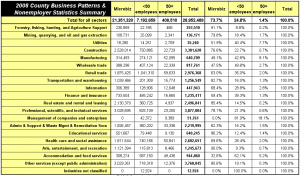

Small business is the engine of economic growth and source of new jobs. This is a perennial favorite, because it's not as true as it seems. There are in the range of 28 million businesses in the USA, with more than 21 million of them being what could be best characterized as "microbusinesses" because they do not have employees other than their owners. The data are from the 2008 County Business Patterns and the 2008 Nonemployer Statistics (2009 data will be available sometime in July). The nonemployers are proprietors, partners, Sub-S corporations, and others that declare their incomes on tax returns and do not issue W2 forms. Aside from businesses, there are moonlighters, hobbyists, and various people who get paid on 1099s. Most of these microbusinesses only have revenues of a few thousand dollars, but many are the revenues of professional positions, such as lawyers and accountants, or independent sales representatives, and many other positions. These microbusinesses are rarely considered in economic discussions. (click to enlarge)

While it is true that small business employment is more than half of total employment in the US, the reality is that small business needs large businesses to be healthy, since so many small businesses sell their services to large businesses. What's a large business? While the definition varies a bit by industry, the one that fits most is having 500 or more employees. In the chart above, I used 50 employees as the cutoff, and even when I ignore the microbusinesses, the 50+ group is only 5.6% of total business establishments. Of course, small businesses create more employment, because there are so many of them. But small businesses also lose the most employees.

Small businesses are essential to the economy, but stimulating employment in small businesses alone is not the answer. Stimulating the demand for the services and goods produced by small businesses, often in service to large businesses, is far more important. All big businesses started as small businesses that found a market for what they offered. When that market does not demand goods and services, there will be no increase in small business employment.

Small business is overly burdened by regulatory costs. This is true, and not enough small businesses realize it. While all businesses have regulatory costs, some good, some bad, some seriously detrimental to doing business, the biggest problem is that regulatory costs are so hard to measure. In many ways, it's not that a small business is burdened by regulatory costs that is the problem, it's the cost of starting a new business and taking the first steps that is. The risks of starting a business are bad enough; when you add the costs of regulatory compliance that must be met well before a unit of goods or services is produced, that is a drag on the economy that few recognize. To understand economics, one must have a great appreciation of the unseen, not just the physical manifestations of commerce. No one can see a decision not to do something, and regulations often create vacuums in economic activity. As economist Milton Friedman warned, all regulations are applied to existing businesses, but no one seems to realize the unintended consequences that may affect businesses yet to be started.

It's worth taking a look at some of the regulatory costs of business, and I strongly recommend that all small business owners aggressively remind their legislators, whether local, state, or national, and especially their advocates, such as Chambers of Commerce, about these resources. The Small Business Administration released a report in September 2010 that estimated the costs of regulation as more than $1.7 trillion dollars in 2008. The report is quite an eye-opener; it should be, because that $1.7 trillion was before the recession, and before the new regulations issued in light of the financial collapse and new health care plans. A small manufacturing business pays, according to the government's own data, more that $14,000 per employee, in compliance costs. If anyone questions why manufacturers consider going overseas, show them table 14, page 50 (p54 of the PDF file). The combination of fast-growing markets alone is enough to capture company interests, but combine that with lower compliance costs, and the decision can be quite compelling.

Also take a look at the Competitive Enterprise Institute's Ten Thousand Commandments report for 2011 further discusses the regulatory environment, with one of its key indicators being the number of pages in the Federal Register, where all new regulations and laws are reported. The report states "Regulatory costs now comfortably exceed the cost of individual income taxes, and those costs vastly exceed revenue from corporate taxes... regulatory costs now tower over the estimated 2010 individual income taxes of $936 billion... Corporate

income taxes, estimated at $157 billion, are dwarfed by regulatory costs... regulatory cost levels exceed the level of pretax corporate profits..."

Are small businesses disproportionately affected by regulatory costs? Yes, and those costs divert resources away from productive activities in the same manner that they may prevent hazards or problems that the regulations were created for. But the ultimate costs are that the economy is deprived of more small businesses because the barriers to entry that regulations are inadvertently created. In the end, regulatory costs and business taxes, are all in the prices paid in the marketplace by consumers and other businesses.

While it is true that small business employment is more than half of total employment in the US, the reality is that small business needs large businesses to be healthy, since so many small businesses sell their services to large businesses. What's a large business? While the definition varies a bit by industry, the one that fits most is having 500 or more employees. In the chart above, I used 50 employees as the cutoff, and even when I ignore the microbusinesses, the 50+ group is only 5.6% of total business establishments. Of course, small businesses create more employment, because there are so many of them. But small businesses also lose the most employees.

Small businesses are essential to the economy, but stimulating employment in small businesses alone is not the answer. Stimulating the demand for the services and goods produced by small businesses, often in service to large businesses, is far more important. All big businesses started as small businesses that found a market for what they offered. When that market does not demand goods and services, there will be no increase in small business employment.

Small business is overly burdened by regulatory costs. This is true, and not enough small businesses realize it. While all businesses have regulatory costs, some good, some bad, some seriously detrimental to doing business, the biggest problem is that regulatory costs are so hard to measure. In many ways, it's not that a small business is burdened by regulatory costs that is the problem, it's the cost of starting a new business and taking the first steps that is. The risks of starting a business are bad enough; when you add the costs of regulatory compliance that must be met well before a unit of goods or services is produced, that is a drag on the economy that few recognize. To understand economics, one must have a great appreciation of the unseen, not just the physical manifestations of commerce. No one can see a decision not to do something, and regulations often create vacuums in economic activity. As economist Milton Friedman warned, all regulations are applied to existing businesses, but no one seems to realize the unintended consequences that may affect businesses yet to be started.

It's worth taking a look at some of the regulatory costs of business, and I strongly recommend that all small business owners aggressively remind their legislators, whether local, state, or national, and especially their advocates, such as Chambers of Commerce, about these resources. The Small Business Administration released a report in September 2010 that estimated the costs of regulation as more than $1.7 trillion dollars in 2008. The report is quite an eye-opener; it should be, because that $1.7 trillion was before the recession, and before the new regulations issued in light of the financial collapse and new health care plans. A small manufacturing business pays, according to the government's own data, more that $14,000 per employee, in compliance costs. If anyone questions why manufacturers consider going overseas, show them table 14, page 50 (p54 of the PDF file). The combination of fast-growing markets alone is enough to capture company interests, but combine that with lower compliance costs, and the decision can be quite compelling.

Also take a look at the Competitive Enterprise Institute's Ten Thousand Commandments report for 2011 further discusses the regulatory environment, with one of its key indicators being the number of pages in the Federal Register, where all new regulations and laws are reported. The report states "Regulatory costs now comfortably exceed the cost of individual income taxes, and those costs vastly exceed revenue from corporate taxes... regulatory costs now tower over the estimated 2010 individual income taxes of $936 billion... Corporate

income taxes, estimated at $157 billion, are dwarfed by regulatory costs... regulatory cost levels exceed the level of pretax corporate profits..."

Are small businesses disproportionately affected by regulatory costs? Yes, and those costs divert resources away from productive activities in the same manner that they may prevent hazards or problems that the regulations were created for. But the ultimate costs are that the economy is deprived of more small businesses because the barriers to entry that regulations are inadvertently created. In the end, regulatory costs and business taxes, are all in the prices paid in the marketplace by consumers and other businesses.

While it is true that small business employment is more than half of total employment in the US, the reality is that small business needs large businesses to be healthy, since so many small businesses sell their services to large businesses. What's a large business? While the definition varies a bit by industry, the one that fits most is having 500 or more employees. In the chart above, I used 50 employees as the cutoff, and even when I ignore the microbusinesses, the 50+ group is only 5.6% of total business establishments. Of course, small businesses create more employment, because there are so many of them. But small businesses also lose the most employees.

Small businesses are essential to the economy, but stimulating employment in small businesses alone is not the answer. Stimulating the demand for the services and goods produced by small businesses, often in service to large businesses, is far more important. All big businesses started as small businesses that found a market for what they offered. When that market does not demand goods and services, there will be no increase in small business employment.

Small business is overly burdened by regulatory costs. This is true, and not enough small businesses realize it. While all businesses have regulatory costs, some good, some bad, some seriously detrimental to doing business, the biggest problem is that regulatory costs are so hard to measure. In many ways, it's not that a small business is burdened by regulatory costs that is the problem, it's the cost of starting a new business and taking the first steps that is. The risks of starting a business are bad enough; when you add the costs of regulatory compliance that must be met well before a unit of goods or services is produced, that is a drag on the economy that few recognize. To understand economics, one must have a great appreciation of the unseen, not just the physical manifestations of commerce. No one can see a decision not to do something, and regulations often create vacuums in economic activity. As economist Milton Friedman warned, all regulations are applied to existing businesses, but no one seems to realize the unintended consequences that may affect businesses yet to be started.

It's worth taking a look at some of the regulatory costs of business, and I strongly recommend that all small business owners aggressively remind their legislators, whether local, state, or national, and especially their advocates, such as Chambers of Commerce, about these resources. The Small Business Administration released a report in September 2010 that estimated the costs of regulation as more than $1.7 trillion dollars in 2008. The report is quite an eye-opener; it should be, because that $1.7 trillion was before the recession, and before the new regulations issued in light of the financial collapse and new health care plans. A small manufacturing business pays, according to the government's own data, more that $14,000 per employee, in compliance costs. If anyone questions why manufacturers consider going overseas, show them table 14, page 50 (p54 of the PDF file). The combination of fast-growing markets alone is enough to capture company interests, but combine that with lower compliance costs, and the decision can be quite compelling.

Also take a look at the Competitive Enterprise Institute's Ten Thousand Commandments report for 2011 further discusses the regulatory environment, with one of its key indicators being the number of pages in the Federal Register, where all new regulations and laws are reported. The report states "Regulatory costs now comfortably exceed the cost of individual income taxes, and those costs vastly exceed revenue from corporate taxes... regulatory costs now tower over the estimated 2010 individual income taxes of $936 billion... Corporate

income taxes, estimated at $157 billion, are dwarfed by regulatory costs... regulatory cost levels exceed the level of pretax corporate profits..."

Are small businesses disproportionately affected by regulatory costs? Yes, and those costs divert resources away from productive activities in the same manner that they may prevent hazards or problems that the regulations were created for. But the ultimate costs are that the economy is deprived of more small businesses because the barriers to entry that regulations are inadvertently created. In the end, regulatory costs and business taxes, are all in the prices paid in the marketplace by consumers and other businesses.

While it is true that small business employment is more than half of total employment in the US, the reality is that small business needs large businesses to be healthy, since so many small businesses sell their services to large businesses. What's a large business? While the definition varies a bit by industry, the one that fits most is having 500 or more employees. In the chart above, I used 50 employees as the cutoff, and even when I ignore the microbusinesses, the 50+ group is only 5.6% of total business establishments. Of course, small businesses create more employment, because there are so many of them. But small businesses also lose the most employees.

Small businesses are essential to the economy, but stimulating employment in small businesses alone is not the answer. Stimulating the demand for the services and goods produced by small businesses, often in service to large businesses, is far more important. All big businesses started as small businesses that found a market for what they offered. When that market does not demand goods and services, there will be no increase in small business employment.

Small business is overly burdened by regulatory costs. This is true, and not enough small businesses realize it. While all businesses have regulatory costs, some good, some bad, some seriously detrimental to doing business, the biggest problem is that regulatory costs are so hard to measure. In many ways, it's not that a small business is burdened by regulatory costs that is the problem, it's the cost of starting a new business and taking the first steps that is. The risks of starting a business are bad enough; when you add the costs of regulatory compliance that must be met well before a unit of goods or services is produced, that is a drag on the economy that few recognize. To understand economics, one must have a great appreciation of the unseen, not just the physical manifestations of commerce. No one can see a decision not to do something, and regulations often create vacuums in economic activity. As economist Milton Friedman warned, all regulations are applied to existing businesses, but no one seems to realize the unintended consequences that may affect businesses yet to be started.

It's worth taking a look at some of the regulatory costs of business, and I strongly recommend that all small business owners aggressively remind their legislators, whether local, state, or national, and especially their advocates, such as Chambers of Commerce, about these resources. The Small Business Administration released a report in September 2010 that estimated the costs of regulation as more than $1.7 trillion dollars in 2008. The report is quite an eye-opener; it should be, because that $1.7 trillion was before the recession, and before the new regulations issued in light of the financial collapse and new health care plans. A small manufacturing business pays, according to the government's own data, more that $14,000 per employee, in compliance costs. If anyone questions why manufacturers consider going overseas, show them table 14, page 50 (p54 of the PDF file). The combination of fast-growing markets alone is enough to capture company interests, but combine that with lower compliance costs, and the decision can be quite compelling.

Also take a look at the Competitive Enterprise Institute's Ten Thousand Commandments report for 2011 further discusses the regulatory environment, with one of its key indicators being the number of pages in the Federal Register, where all new regulations and laws are reported. The report states "Regulatory costs now comfortably exceed the cost of individual income taxes, and those costs vastly exceed revenue from corporate taxes... regulatory costs now tower over the estimated 2010 individual income taxes of $936 billion... Corporate

income taxes, estimated at $157 billion, are dwarfed by regulatory costs... regulatory cost levels exceed the level of pretax corporate profits..."

Are small businesses disproportionately affected by regulatory costs? Yes, and those costs divert resources away from productive activities in the same manner that they may prevent hazards or problems that the regulations were created for. But the ultimate costs are that the economy is deprived of more small businesses because the barriers to entry that regulations are inadvertently created. In the end, regulatory costs and business taxes, are all in the prices paid in the marketplace by consumers and other businesses.

About Dr. Joe Webb

Dr. Joe Webb is one of the graphic arts industry's best-known consultants, forecasters, and commentators. He is the director of WhatTheyThink's Economics and Research Center.

Video Center

WhatTheyThink is the official show daily media partner of drupa 2024. More info about drupa programs

© 2024 WhatTheyThink. All Rights Reserved.