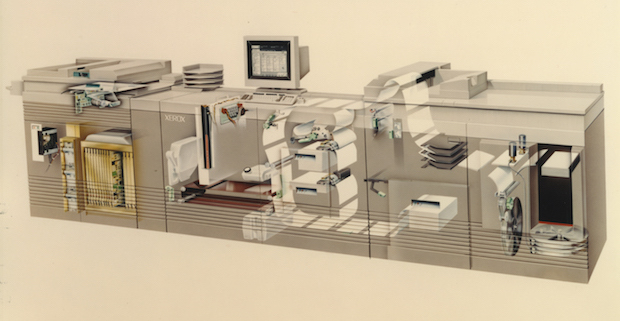

Xerox DocuTech 135 Launch Publicity Image (Courtesy Xerox Corp.)

It’s hard to believe that the Xerox DocuTech Production Publisher was launched 25 years ago last month. This was truly a breakthrough product that is credited with launching the print-on-demand market and ultimately generated billions of dollars of revenue for Xerox and its customers. For the first time ever, three distinct technologies – high resolution scanning, laser imaging, and xerography – were combined into a single publishing solution, delivering offset-like quality at a lower cost and in an unprecedented turnaround time. For those of us who were involved in the program, it was truly a unique experience, the kind of opportunity that doesn’t come along very often.

I had the opportunity to speak recently with Randy Hube who is currently the Manager of Litigation and Strategic Technical Services in the Xerox Intellectual Property Operation. While I was involved with the program beginning in late 1989 in sales in Silicon Valley, Randy had a much deeper and longer involvement. It was great to take a trip down memory lane with him as we talked about how the program evolved.

Randy started with Xerox 39 years ago, and for a good portion of his career, he worked on the DocuTech program. In 1981, before the program was even really underway, he worked with a group doing exploratory concept work on digital publishing that led to the inception of the formal DocuTech program around 1983, and he stayed involved in the program through the late 1990s, when he moved to the Intellectual Property Operation. Randy also is responsible for the Xerox Archives, an important repository of historical information on the many contributions Xerox has made to the industry over the years, including DocuTech.

Although no one really envisioned what DocuTech would ultimately become when work began in 1981, there were a number of engineers working on all of the different concepts that would ultimately go into a digital publishing system. “We were talking to publishers like John Wiley & Sons,” Hube explains, “about the requirements for such a system, including printing, scanning and advanced system control and user interface concepts. Remember that at that time, the mouse was just evolving and touch screen systems had barely emerged; DocuTech ultimately had both.”

Back then, people in Xerox were using the term “electronic reprographics.” Hube continues, “We understood how to sell light-lens copiers into commercial print and in-plant (centralized reproduction departments or CRDs), but primarily for copying and duplicating tasks. Although we had been selling printers into the data center environment for a few years at that point, this was mostly transactional printing and that technology hadn’t really penetrated into the commercial print or CRD environments. A lot of the time in those early years was spent understanding the very different language and unique requirements of the commercial printing industry.”

Hube explains that the DocuTech had to be built from the ground up. “We had very little previously in existence that we could build upon,” he says. “To meet the necessary performance levels, we had to come up with our own processors, system architect and our own computer operating systems. Additionally, all the control software as well as system diagnostics were created from scratch, too. There was a great deal to do to build all of the rich feature set this system offered. I know the marketing team wanted even more features than we could deliver. I would write descriptions for 100 features, and they still wanted more! Remember that the whole desktop publishing revolution was happening around that time, and there were a lot of players. We had to be able to take output from any source and be able to run it reliably. When you combined the quantity of features and requirements, the testing matrix was staggeringly large.”

As it turned out, the initial product that was launched was standalone, but Xerox knew the market wanted network connectivity, and it took Xerox a couple more years to make that available. Third parties like John Lacagnina of Entire (now President & CEO of SoftPrint Holdings and printernet, Inc.) and Denise Miano, Founder and President of NEPS (now a Taylor Corp. company) actually were able to offer some level of network connectivity prior to the formal Xerox offering in 1992.

The project was enormous. In a Xerox blog post about the anniversary, a reference is made to a team consisting of several thousand engineers who drew upon Xerox technology from the copier, printer and workstation worlds. In the blog, Hube says, “While it’s true we produced the first personal computer but failed to market it successfully, those efforts did prove pivotal in equipping the DocuTech team with the tools and hardware to build a superior product.” He explains that for a year prior to product launch [including the beta cycle], there were 40 DocuTechs running in a Webster, New York, test lab, and even with that capacity, the company was unable to test the full spectrum of possibilities. “People were using it in ways we could never imagine,” he says. “For example, we placed machines at the American Printing House for the Blind where they were doing unique work we had never anticipated. We wanted to bring the product to market in a way that was reliable, so we had to make hard choices that some functionality [like network connectivity and external disk storage] wasn’t going to be available at launch.” Offline disk storage turned out, perhaps, to be a bigger issue than anticipated as on-board system storage quickly filled up, and a solution was made available within six months of launch. By 1994, Xerox had added a Sun workstation on the front end with software that became known as DocuSP, and the product at that point was a full network citizen. Hube adds, “When we were doing the design work, the notion of print on demand hadn’t really emerged. We probably started to understand the need in 1988 and 1989, but at that point, we were locked in to functionality, and it took a couple more years to fully realize the capabilities required.”

In fact, I remember being in a meeting with members of the development and launch team at a pharmaceutical company that ultimately became a beta site. The customer immediately grasped the concept and how it could change their business, but was quite surprised that at launch, there would be no way to send files over the network or export scanned files. Nonetheless, they became a very successful beta site and were able to utilize existing capabilities while pushing for more. A huge application for them was producing forms to be used in clinical trials that printed on carbonless paper, and they were a key driver in overcoming the challenges this important application offered.

The original DocuTech, according to Hube, was designed for 800,000 to 850,000 prints per month. “But,” he says, “it was so well built, it could handle more. We thought it would be running one shift five days a week, but we were finding that people were running them up to 24/7, and we watched volumes exceed expectations by as much as a factor of three or more.” In my Silicon Valley experience, we typically told potential commercial print customers they should have at least 1.2 million impressions per month to be profitable with the system. How reliable was the system? “One of the original DocuTechs is still running in Canada,” says Gary Walker, Manager of Global Communications at Xerox. According to Xerox,production of the DocuTech line ceased in late 2013, but more than 1,500 DocuTech systems have been confirmed to still be actively producing output worldwide.

Hube concludes: “One thing that hasn’t been talked about, and one of the really great things about Xerox over the years, is than when you have some of these great products come to market, it is the result of a large team that worked hard. That team was together for many years. They were all very strong people in their respective fields, some of the best product development and software people we could find. They did a great job and worked hard, and they were on mandatory overtime for years. Everyone knew that we were working on something groundbreaking, and everyone was giving it extra effort because of that. No one wanted to be responsible for it not meeting the mark or timeline. Today, we all talk about how you could go through Building 129 in Webster, and it was humming from 6:30 AM to 9:30 PM six days a week. That was one of the most amazing work experiences we had ever had. The amount of learning, teamwork and effort was incredible. The late Chip Holt was often called the father of the DocuTech, not that he was the originator, but he led the program through the development and launch. The team he assembled consisted of very experienced program management professionals. That team was big; we easily had 1,500 people involved. We were coordinating board development in El Segundo, California, with software development on both the East and West Coasts, and print engine development in Building 207 in Webster. This was the first product that not only scanned an image but displayed it on the screen and allowed you to do electronic cut and paste on the screen and then print the revised document. Further, you could attach devices in line to do all kinds of finishing. It was a great product, and every engineer should have the opportunity to work on a product like this at least once in their career.”

While I wasn’t personally involved to the depth and extent as the team Hube describes, I still feel extremely honored to have been even a small part of the program out in Silicon Valley. It certainly changed the way people in the Valley produced technical documentation, and it was exciting to be part of that transformation. Later, I was able to work on Frank Steenburgh’s marketing team out of Rochester that brought DocuSP to market, and while the early achievements were amazing, that final step of high-powered network connectivity really fulfilled the promise that was envisioned more than a decade before.

Discussion

By Alan Roberts on Nov 16, 2015

I was fortunate to work for The Printing House that installed the first docutech and Igen in Canada. Both were exciting new pieces of technology. They are still workhorses where I now hang my hat at DATA Group of Companies

By Jo Oliphant on Nov 16, 2015

As a technical specialist on this product in the early 90's it was a complete joy to work with.

The engineering was really inspirational and to this day is still an incredible achievement given the fact that there was little to nothing to repurpose from within the existing technologies of the day.

Discussion

Join the discussion Sign In or Become a Member, doing so is simple and free