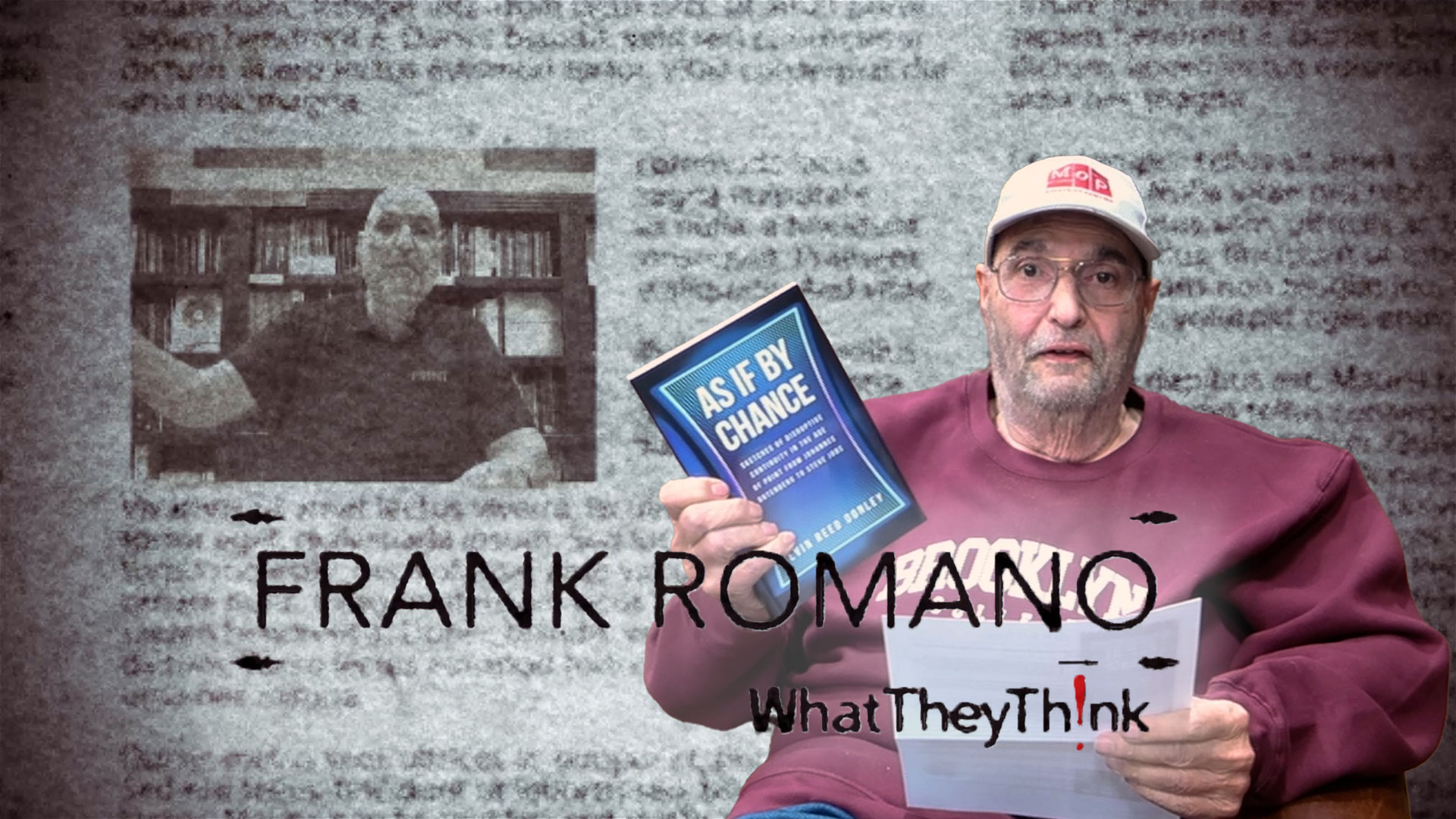

A quartet of objects made with a color 3D printer from Mcor Technologies

3D printing doesn’t have much in common with 2D printing beyond the unabbreviated part of the name. But, there’s one 3D printing process that comes unexpectedly close to conventional print production in the raw materials it uses: ordinary office paper, adhesive, and, for color output, water-based inkjet ink.

It’s known as selective deposition lamination (SDL), and an Irish company called Mcor Technologies claims to be the sole supplier of paper-based 3D printing systems built around it. Of all the 3D printing solutions on display at the recent Inside 3D Printing conference and expo in New York City, only Mcor’s appeared to parallel any of the norms of conventional printing—such as the ICC profile its devices support when printing in color.

Like the other forms of 3D printing, SDL is an additive manufacturing process that “prints” solid objects by accreting build material in layers until the piece is fully formed. SDL differs from the others, though, in that the only substance it prints in layers is paper—a medium, according to Mcor, that can surpass other build materials in terms of aesthetics, durability, and economy.

Mcor’s 3D printers feed, image, bind, and trim sheets of paper in a sequence of steps that would seem generally familiar in any 2D printing shop. Despite the functional crossover, however, the nature of the steps and the finished pieces they lead to are a world apart from conventional production on offset or digital equipment.

First, a sheet of paper is attached to the build plate—the part of the machine where the printing takes place. The initial sheet gets a layer of adhesive that varies in density according to the design of the thing to be printed (more glue is used for the part itself; less for the excess supporting material that eventually will be trimmed away). A second sheet of paper is deposited onto the first, and a tungsten carbide blade cuts the outline of the object on the second sheet to define its shape.

The cut sheet takes adhesive, another sheet goes on top of it, and the process is repeated until all of the layers have been outlined and deposited. Removal of supporting material—layered paper that is not part of the finished object—can be done by hand or with the help of a pair of tweezers. (Mcor calls this step “weeding.”)

Control software built into Mcor printers “slices” standard 3D input file formats into printable layers of the same thickness as the paper. For 3D printing in full process color, Mcor’s Iris machine uses a modified 2D inkjet printer that adds color to the sheets where needed before the layering sequence begins. The CMYK ink is a proprietary, water-based fluid that permeates the paper all the way to the edge to assure full coloration of the finished object.

Last year, Mcor announced that it had modified the Iris to become the first 3D printer to include an ICC (International Color Consortium) profile: a software-based specification, universally used in conventional printing, that enables different imaging and printing devices to create color within a standardized and consistent color space. With the help of the profile, says Mcor, the Iris can accurately reproduce color from other sources with the richness and intensity of display seen on computer screens.

All of this is done using ordinary sheets of either 80 gsm A4 standard office paper or 20 lb. U.S. standard letter paper. As a build material, says Mcor, paper in 3D printed form resembles the wood from which it comes in surface texture and warmth. Paper is cheaper than the polymers, resins, powders, and extrudable materials used by other 3D processes, and objects made of it can be decorated, treated for additional durability, and readily recycled, the company says.

Mcor was established by brothers Dr. Conor MacCormack and Fintan MacCormack in 2004. Their aim was to make 3D printing broadly accessible with affordable and easy-to-use printing systems. Since then, Mcor devices have been installed by service bureaus, prototyping studios, architectural and design agencies, colleges and universities, and medical practitioners.

Among the latter are doctors at a Belgian research university who have used SDL to create realistic replicas of bone structures to guide them during facial reconstruction surgery. In another application involving body parts, museum professionals in the U.K. replicated the mummified hand of an Egyptian woman who lived at some point between 1550 B.C. and 32 B.C.

Closer to conventional printing markets was Mcor’s adoption by Digicopy, an Italian reprographics firm that primarily serves colleges and universities in that country. In the U.S., students at Robert E. Lee High School in Baytown, TX, explored computer-aided design for engineering and architecture by creating gears and similar objects on an Mcor Matrix 300+ printer. The prototyping lab at Vincennes University (Vincennes, IN) discovered it could make parts from paper on a Matrix printer at about one-seventh of the material cost of forming them with a plastic-based 3D printer.

The School of the Art Institute of Chicago uses the ICC-compliant Iris color printer as a teaching and research tool. With its eye on further penetrating the educational market, Mcor offers schools three years of consumables (adhesives and cutting blades) at no cost with the purchase of a device.

Where 3D printing by Mcor or any other developer fits into the business model of 2D graphic communications isn’t yet clear. Producers of packaging and structural printing almost certainly could use it for prototyping. Some in-plants might want to adopt it to keep their parent organizations from outsourcing whatever 3D printing they may decide to do. It’s not hard to envision a quick printer offering 3D output as a walk-in retail service.

The Inside 3D Printing event was full of examples of the technology’s usefulness for customized manufacturing—the specialty of conventional printing for as long as it has existed. Although Mcor has many competitors, it may have an edge in the mainstream printing industry because its value proposition begins with the same thing—a blank sheet of paper.

Discussion

Join the discussion Sign In or Become a Member, doing so is simple and free