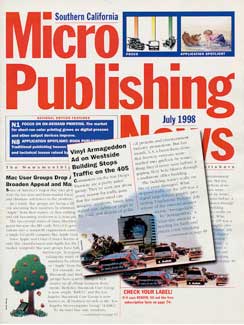

One afternoon back in the summer of 1998, I was driving on the 405 Freeway through downtown Los Angeles, and traffic—as it was wont to do—slowed to a crawl, for any one of the several hundred reasons that traffic slows to a crawl in Los Angeles. As I inched forward, I began to see what, it turned out, was the cause of the gridlock: a massive building wrap advertising the then-new movie Armageddon. The vinyl graphic made it look as if there was a smoking hole through the building, as if it had been hit by a meteor. This was some time before cameraphones, but we managed to scrounge up a photo of it, and we covered the story in the Southern California edition of the late lamented Micro Publishing News. Thus was my introduction to the world of superwide-format printing.

Although there is no true standard minimum width for what constitutes “wide-format,” it is generally acknowledged that 24 inches and greater is considered “wide.” Similarly, the term “superwide-format” is also not definitively classified. However, it’s common to see 72 inches wide and greater as constituting “superwide.” (Since many things in the graphic arts have more than one term, superwide-format printers are occasionally referred to as “grand-format or even “grande-format.”) Time was, there were very few superwides on the market, and those that did exist typically offered much lower resolutions than smaller machines. That wasn’t necessarily a problem; when you’re printing billboards, signage, and building wraps (like flaming meteor wreckage)—the emblematic applications for superwides, then and now—you could get away with fairly low resolution, as the graphics are meant to be viewed at a distance.

Today’s superwides, which are proliferating in terms of number of models on the market, boast much better image quality, resolution, speed, and versatility than their forebears.

Why So Big?

While some applications for superwides are pretty obvious—building wraps à la Armageddon, billboards, et al.—some may not be. For print providers who rely on tiling—assembling, jigsaw puzzle-like, several smaller wide-format graphics to create a larger image—being able to print the entire graphic in one go is an attractive option.

Some print providers find it more efficient to gang two or even three smaller wide-format jobs on a single superwide roll—or install more than one smaller roll—and print them simultaneously. In those cases, it may be more convenient and space/staff-saving to have a single superwide take the place of what would have been two or more smaller units. It is also more economical to generate maximum square footage in minimum time.

That said, there is more to a superwide-format printer than just a scaled up version of a smaller unit. Special considerations include having the space for the hardware, storing and handling large, cumbersome materials, file processing, finishing, transportation, and installation. Think of the difference between hanging an 11 x 17-inch poster and hanging wallpaper, and you start to get the idea. Especially if you are dealing with rigid substrates, superwide-format can make even wide-open facilities seem cramped in no time.

Options Galore

Compared to the units of yesteryear, there are more options for superwides today. There are rollfeds that print on flexible materials like paper, canvas, and vinyl, flatbeds that can print on rigid materials, and even some hybrid models. There are solvent-ink units and UV models. Speeds are increasing all the time. New printhead designs and the ability to utilize newer inks also means the resolution of superwides is as good as smaller wide-format machines—which means they don’t have to be relegated to jobs that are viewed from a distance.

How Big Can It Get?

In terms of technology, there is probably no theoretical limit to how large machines can get. The current max is just shy of 200 inches wide. That’s about 17 feet, or over 5½ yards. Not even taking into account the size of the machine, you have to concern yourself with where you are going to store, and how you are going to handle, your media—assuming substrate manufacturers will keep up with escalating hardware widths, or at least with the variety that wide-format printers have come to expect. Also, exceedingly wide media can be a bear to feed consistently and smoothly through the print engine. And do you really want to have to do remakes at that size? Finishing equipment likewise will need to “go big,” as well. Elsewhere in the workflow, think about how big a print file for a 200+-inch graphic will be. So there are some fairly practical barriers to the development of what we may want to call “titanic-format” printers. There are, of course, by no means unsurmountable.

Ultimately, though, the maximum superwide size will be dictated by what the market demands. Would productivity gains from titanic-format printers make them an attractive option? Will end users want larger output for, say, larger billboards or building wraps? Are there any new applications that such massive output would engender? The possibilities are endless.

Just keep them away from the 405 Freeway.

Discussion

Join the discussion Sign In or Become a Member, doing so is simple and free